Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

In a discreet yet politically charged move, the US Department of State has flagged Turkish Hizbullah as a terrorist entity on its Terrorist Exclusion List (TEL), a mechanism that targets immigration, visa and entry controls.

The designation effectively empowers US authorities to bar or deport any foreign national associated with the group, even though Turkish Hizbullah has not been listed under the broader and more public Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) framework.

Turkish Hizbullah, not to be confused with its Lebanese namesake even though both are linked to Iran, emerged in the 1980s as a Sunni Kurdish Islamist group that waged a violent campaign of assassinations, kidnappings and brutal torture across Turkey’s southeast. The organization reached its height in the 1990s, when police raids uncovered secret execution chambers and hours of videotaped torture sessions, earning the group a reputation as one of Turkey’s most violent underground Islamist movements.

The group’s founder, Hüseyin Velioğlu, was killed in a police raid in 2000, prompting Turkish Hizbullah to retreat from armed militancy and rebuild itself through religious, charitable and political fronts in order to sustain its network. Over time, its ideological network coalesced into the Free Cause Party (HÜDA-PAR), which now operates openly as a legal political organization.

Hizbullah struck a secret deal with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2014, with its political arm endorsing Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) in exchange for the release of imprisoned Hezbollah members convicted of violent crimes. By 2023 HÜDA-PAR had formally joined Erdogan’s electoral alliance, fielding candidates under the AKP banner, a milestone that marked the first appearance of Hizbullah-linked figures on Turkey’s national ballot.

Erdogan fulfilled his part of the bargain by issuing a series of presidential pardons and securing early releases for convicted Hizbullah members. In August 2022, 19 militants serving aggravated life sentences for 91 murders were freed after the government quietly arranged their release in exchange for political support.

In 2025, two Hizbullah operatives convicted of attempting to overthrow the constitutional order were granted presidential pardons. To date, roughly 400 Hizbullah members have been released from Turkish prisons through mechanisms facilitated by the government, while opposition politicians, journalists and critics continue to face harsher treatment and wrongful imprisonment.

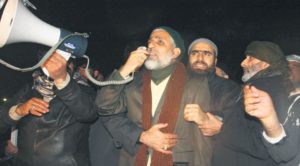

Turkish Hizbullah’s contemporary leadership remains ideologically militant. Its supreme religious leader, Edip Gümüş, a fugitive believed to be residing in Iran , in 2023 called for a “global jihad against Jews,” pledging arms and funds for anti-Israel operations. The organization has also hosted Hamas representatives in Turkey, participating in anti-Israel demonstrations coordinated by pro-government municipalities and staged rallies in front of the US Embassy and consulates as well as NATO installations.

Nordic Monitor previously published confidential police and military intelligence documents tracing significant funding and training links between Turkish Hizbullah and Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force. One police report from Diyarbakır revealed monthly payments of about $100,000 from Iran to Hizbullah, along with larger lump-sum transfers for special operations. The documents indicated that Iran had established a Hizbullah espionage unit tasked with surveillance of military installations in Turkey, including NATO-linked radar bases in Malatya province. Hizbullah operatives reportedly collected video footage and passed it to Iranian handlers.

Despite this intelligence, the Erdogan government shut down the investigation into Hizbullah’s Iranian connections. The prosecutor leading the Quds Force inquiry was dismissed, case files were buried and the probe was formally closed, illustrating how Turkish Hizbullah has evolved from a purely domestic actor into a regional ideological ally for Iran-backed networks and pro-Palestinian Islamist factions.

By invoking the Terrorist Exclusion List rather than the FTO designation, Washington is signaling concern without provoking a full diplomatic confrontation with Ankara. Established under Section 411 of the USA PATRIOT Act, the TEL is primarily an immigration tool, allowing US authorities to deny entry or deport individuals affiliated with listed organizations. Groups on the list are treated as terrorist entities for visa and immigration purposes but are not automatically subject to financial sanctions.

In practice, this makes the measure a quiet yet potent form of political censure, a way for Washington to mark Turkish Hizbullah as a continuing security risk while avoiding the economic and diplomatic fallout of a broader sanctions regime.

Beyond its political wing, HÜDA-PAR, Turkish Hizbullah controls an extensive network of entities in Turkey and abroad. These include Doğru Haber, the group’s official media mouthpiece; İlke Haber Ajansı (İLKHA), a news wire service; Rehber TV, a religious television channel; and associations such as Mustazaf-Der and Âlimler ve Medreseler Birliği as well as foundations including Peygamber Sevdalıları Vakfı and Yetimler Vakfı.

The organization also maintains overseas fronts, especially in Europe, where large Turkish and Kurdish diaspora groups live. In Germany, for example, the charity Orphans Help e.V. operates under the guise of humanitarian aid but is directly connected to Turkish Hizbullah’s European network.

For Erdogan, the US action adds an uncomfortable layer to an already delicate balancing act. His government has long relied on HÜDA-PAR’s grassroots network in Kurdish-majority provinces to erode support for the pro-Kurdish opposition. In return, Hizbullah-linked figures have gained political legitimacy and state protection under the AKP’s umbrella.

The US listing, however, reframes that alliance internationally, highlighting the contradiction between Ankara’s domestic political partnerships and its obligations as a NATO member and counterterrorism partner.

The implications of Washington’s move extend beyond Turkey’s borders. The immigration-based designation could complicate travel and visa applications for Hizbullah-linked individuals, hinder their fundraising efforts abroad and attract scrutiny to financial transfers through Turkish and regional banking systems.

It also underscores Washington’s growing concern that Turkey has become a permissive environment for radical Islamist actors, from Hamas operatives to veterans of ISIS and al-Qaeda, who enjoy relative freedom under Ankara’s Islamist-leaning administration.

Inside Turkey the decision resonates deeply among the victims of Hizbullah’s 1990s campaign of terror. Many have long decried the state’s rehabilitation of convicted killers, while critics and opponents accuse Erdogan of transforming former militants into political allies. For these critics the US designation provides long-overdue international recognition that the group’s violent legacy cannot be whitewashed through political partnerships or religious rhetoric.

Ultimately, Washington’s inclusion of Turkish Hizbullah on the Terrorist Exclusion List functions as a strategic warning shot, one that exposes the contradictions within Erdogan’s Islamist alliances while reaffirming the United States’ prerogative to define terrorism independently of political expediency.

Whether Ankara chooses to ignore the signal or recalibrate its domestic partnerships remains uncertain, but the message from Washington is unmistakable: Alliances with violent Islamists, however electorally convenient, carry international consequences.