Levent Kenez/Stockholm

Turkey’s prison population has reached an unprecedented level, hitting the highest figure in the country’s modern history, according to official data released on September 1, 2025. The surge in inmate numbers reflects not only rising crime but also the government’s continued crackdown on political dissent.

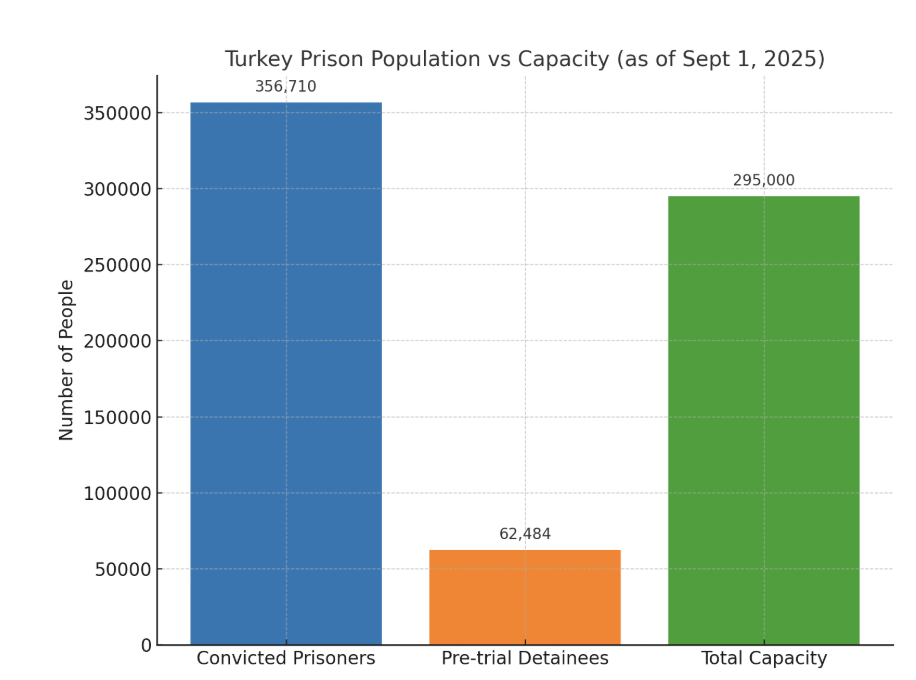

Figures from the Directorate General of Prisons and Houses of Detention show that as of September 1, Turkish prisons hold 419,194 individuals. This total includes 356,710 convicted prisoners and 62,484 people in pretrial detention. The number exceeds the official capacity of 295,000 and puts immense strain on the country’s penal system.

The total prison population now surpasses the population of 34 Turkish provinces. To cope with the pressure, the government has accelerated prison construction. Work on 11 new prison facilities is scheduled to begin in 2025, including major projects in Niğde, Tokat and Çorum. The government has allocated 1.2 billion lira for these projects in 2025, with total funding expected to reach 23.5 billion lira (about $840 million) by the end of 2027.

Experts attribute the historic surge in inmate numbers to two intertwined factors: the rise in organized crime and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s policy of jailing political opponents.

The Global Organized Crime Index recently ranked Turkey as Europe’s leading country in terms of state-linked organized crime actors. The presence of mafia groups, drug traffickers and armed networks has grown significantly, exacerbated by years of government tolerance and corruption. Although Turkish authorities launched more than 1,600 operations against criminal groups between mid-2023 and late 2024, critics argue the actions came too late and were insufficient.

At the same time President Erdogan’s government has used the prison system as a political tool. While several amnesty bills were introduced over the past decade, ostensibly to reduce prison overcrowding, they were applied selectively. Hundreds of thousands of convicts, including mafia members and extremists, were released, but political prisoners, dissidents, journalists, academics, activists and perceived opponents of the ruling party were deliberately excluded. This selective application has allowed violent offenders to regain their freedom while keeping critics behind bars, reinforcing the perception that amnesties serve political rather than humanitarian or penal purposes.

According to the Council of Europe’s 2023 report on prison populations (SPACE I), Turkey already accounted for more than one-third of all prisoners in its 46 member states. Of the 1,036,680 total inmates across Europe, Turkey alone held 348,265. This figure dwarfed numbers in countries such as England and Wales with 81,806, France with 72,294, Poland with 71,228 and Germany with 58,098.

The report also shows how easily the Turkish government, which has been criticized by international human rights organizations and the United Nations for the implementation and scope of its counterterrorism law, turns its citizens into terrorist convicts.

According to an analysis by Nordic Monitor based on SPACE I data, 32,006 people convicted of a terrorism-related crime are currently behind bars in Europe.

A total of 30,555 of these people, or 95 percent, are in Turkish prisons. In other words, Turkey hosts almost all prisoners convicted of terrorism in Europe. Turkey is followed by the Russian Federation with 1,026 prisoners, or 3.2 percent of the total. Spain is in third place with 195 inmates.

According to official figures released by the Directorate General of Prisons and Houses of Detention on September 1, 2025 Turkish prisons hold 419,194 individuals.:

The explosion in organized crime has further strained prisons. Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya recently reported that authorities dismantled more than 660 organized crime groups in the past year. While the announcement was framed as a success, critics noted it also exposed years of inaction that allowed criminal empires to flourish unchecked.

Police operations have led to over 11,600 detentions and 4,500 arrests. However, the majority of suspects are quickly released, raising questions about the effectiveness of the judiciary and its ties to both the government and criminal networks. Turkey’s young people have increasingly become entangled in crime from street gangs to drug trafficking, driven by economic hardship and limited opportunities.

Observers note that the rapid expansion of the penal system also carries a political dimension, signaling that the state is prepared to use incarceration not only for criminal offenders but also as part of its broader approach to dissent.

The economic burden of sustaining such a vast prison network is immense. The planned investment of more than 23.5 billion lira by 2027 comes at a time when Turkey faces high inflation, soaring youth unemployment and economic stagnation. Critics argue the money could be better spent on education, job creation or rehabilitation programs rather than expanding incarceration. Yet the government insists that prison expansion is essential for public safety. Officials argue that rising crime rates particularly involving organized crime and youth gangs require robust measures.

Turkey’s record-high prison population highlights a complex convergence of political repression, criminal expansion and systemic failure. With prisons overflowing, the country stands as Europe’s largest jailer by far. For Erdogan’s critics, the numbers tell a story not only of crime but also of democracy in retreat.