Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

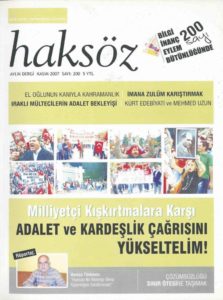

Mustafa Doğan İnal, the personal lawyer of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, criticized a police crackdown on a deadly al-Qaeda group back in 2007 in an opinion piece he wrote for a jihadist publication, Nordic Monitor has learned.

İnal’s attempt to discredit the operation came after the police, acting under the orders of a public prosecutor, rounded up 50 suspects and executed search and seizure warrants at their offices and residences as part of crackdown on al-Qaeda cells in five provinces. He claimed there was no evidence of terrorism and that the case was bogus.

The detentions on January 29, 2007 came after a year and a half of surveillance of the suspects, some of whom were known jihadists with connections to al-Qaeda leadership, and others who had traveled to Afghanistan for training.

One of the key targets of the operation was a man named Haydar Kırkan, also known as Abu-Basher al-Turki or Abu Hani, a senior figure in a Turkish al-Qaeda group that gained notoriety after the 2003 bombings in İstanbul of two synagogues, an HSBC bank branch and the British Consulate General, and a 2008 attack on the US Consulate General in İstanbul. The attacks, perpetrated jointly by al-Qaeda and Turkish jihadist group the Islamic Great East Raiders/Front (İslami Büyükdoğu Akıncılar Cephesi in Turkish, IBDA/C), killed dozens of people.

According to police records, Kırkan’s al-Qaeda commander, Erkem Kozakoğlu, also a Turk, had repeatedly made trips abroad to talk to al-Qaeda leaders, in particular Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, and received instructions on how to coordinate cells in Turkey. His contact with al-Qaeda leadership continued after the killing of al-Zarqawi in a targeted attack by US forces.

Mustafa Doğan İnal’s article that appeared in jihadist publication HakSöz:

Kozakoğlu’s deputy and right-hand man is also a Turk identified as İhsan Dedemoğlu, who was in charge of indoctrination and training. A document recovered from his computer revealed al-Qaeda’s instructions on how to avoid surveillance, while another explained how to use firearms, carry concealed weapons and run counter-intelligence operations. The documents also featured details of secret communications such as the use of burner phones that should be obtained with forged IDs. None of the suspects had in fact registered their phones in their own names.

The police also found that Dedemoğlu, also known as Yusuf under an assumed name, received 3,000 euros from a man in Tunisia for financing terrorist operations. Another associate, Muharrem Gökgöz, had an unlicensed police scanner/transmitter, a prohibited electronic device in Turkey. An examination of the device indicated that it could be used to detonate a bomb from a distance or to access bandwidths used exclusively by the police in Konya province and by the prime minister’s protective detail. Gökgöz also traveled abroad for jihadist battles.

Advancing to various positions in the al-Qaeda network as a trusted member, Kırkan was finally promoted to be external operations planner for the terrorist group, covering Turkey, Europe and Syria. The Pentagon confirmed that 36-year-old Kırkan was killed in a US drone strike in Syria’s Idlib province on October 17, 2016.

However, according to İnal, the president’s lawyer, who wrote for HakSöz, a monthly magazine published by Islamists in Turkey, in the November 2007 issue, the prosecutor had no case against Kırkan or any of his associates. He claimed the police planted evidence on a computer owned by thr suspect Gökgöz which showed instructions on how to build a bomb. He also falsely alleged that no guns were seized when in fact the police found handguns, rifles and ammunition at several locations.

The police intelligence against Kırkan and his associates showed, however, that they were in the planning stages of two bombing plots in Istanbul and Konya provinces. The plot in Konya targeted a hotel where US citizens stayed and was green-lighted by al-Qaeda leadership. Fearing a repeat of the deadly 2003 attack, the police wanted to crack down on the group before they actually managed to carry out the terrorist attacks.

Another plot uncovered from a review of the seized material was a bomb attack targeting the Eczacıbaşı Monrol plant, a facility that manufactures nuclear medical products in the Gebze industrial area, which hosts some 5,000 workers. The plan was to set the factory ablaze and let radioactive material leak to a nearby area to increase fatalities.

One of the raids took place in a madrasa run by al-Qaeda in the basement of a villa for some 30 children aged 7 to 14. During a search of the madrasa, the police found handguns and rifles used in the training of the children. The villa was owned by Memiş Varlı, a suspect in the 2003 al-Qaeda attacks.

Excerpts from the court ruling that convicted al-Qaeda suspects who were defended in an article by the Turkish president’s lawyer, Mustafa Doğan İnal:

The police found CDs and videotapes which showed public buildings that were identified as possible targets by al-Qaeda as well as training videos that showed how to use arms and explosives. A separate document had a list of names that included businesspeople, authors, journalists, politicians and police and military officers who were marked for assassination.

Of 55 people detained in a police sweep, 45 suspects were formally arrested by the court at arraignment. In a follow-up operation, the police also detained an additional suspect identified only by the initials A.B., who had received explosives and bomb-making training in Syria.

The suspects were indicted on June 15, 2007 by a prosecutor in Adana, home to Incirlik Air Base, where US and NATO ally troops were deployed. The case was assigned to the Adana 8th High Criminal Court.

Kırkan, who was facing two outstanding arrest warrants in Adana and Konya provinces, remained a fugitive for nearly a year. When he finally appeared for the second hearing in the case on January 2, 2018, the court surprisingly did not order his arrest and let him go after hearing his defense statement. His release gave rise to speculation that Kırkan and his associates were protected by the Islamist Erdoğan government, which was sympathetic to al-Qaeda ideology.

After his release, Kırkan went to Afghanistan to join his brethren there, skipping follow-up hearings in the case against him, and traveled to Syria in 2011 after the civil war started there. He assumed the name of Abu Kutayba all-Turki in Syria and fought for al-Qaeda until his death in a US drone strike.

Despite the suspects’ claims, the Adana court convicted Kırkan’s associates Dedemoğlu and Gökgöz and sentenced them to six years, three months on conviction of membership in the al-Qaeda terrorist group. The convictions were upheld on regional appeal as well by the Supreme Court of Appeals (Yargıtay).

İnal’s article that exonerates Kırkan and other al-Qaeda members is not the only indication that the Turkish president’s personal lawyer sympathizes with al-Qaeda. In addition to representing Erdoğan and his family members as a lawyer, İnal also represented controversial Saudi businessman Yasin Al-Qadi, a close friend of Erdoğan who for years was listed as an al-Qaeda financier by both the UN Security Council sanction committee and the US Treasury.

İnal also orchestrated the acquittal of all 52 suspects in the case of Tahşiyeciler, an al-Qaeda-linked radical Turkish group led by radical cleric Mehmet Doğan (aka Mullah Muhammed), who openly declared his admiration for Osama bin Laden and called for armed jihad in Turkey.

Erdoğan vigorously defended this indicted cleric, helping him get acquitted by his loyalist judges and prosecutors when he was arrested and tried; jailed journalists who criticized his radical group; and even launched a civil suit in the US against Muslim scholar Fethullah Gülen for defaming the fanatic. The legal scheme for all of this was managed by İnal and his team.

İnal appeared on pro-government TV networks trying to portray Tahşiyeciler members as victims of defamation, although the military and intelligence and law enforcement agencies had flagged the group in early 2000 as dangerous and supportive of al-Qaeda.

Turkey first learned about Doğan and Tahşiyeciler on January 22, 2010, when police raided the homes and offices of dozens of people across Turkey as part of an anti-al-Qaeda sweep. The police discovered three hand grenades, one smoke bomb, seven handguns, 18 hunting rifles, electronic parts for explosives, knives and a large cache of ammunition in the homes of the suspects.

The probe revealed that the terrorist group had sent close to 100 people to Afghanistan for arms training. In seized tape recordings, Doğan was heard calling for violent jihad: “I’m telling you to take up your guns and kill them.” He also asked his followers to build bombs and mortars in their homes, urged the decapitating of Americans, claiming that the religion allows such practices. “If the sword is not used, then this is not Islam,” he stated. According to Doğan, all Muslims were obligated to respond to then-al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden’s armed fight.

Turkey’s crackdown on al-Qaeda groups was dealt a heavy blow when December 2013 corruption cases concerning bribery in Iran sanctions evasion schemes incriminated then-prime minister Erdoğan, his family members and his business and political associates. Erdoğan launched a major shakeup in the police and judiciary, reassigning investigators who were looking into graft as well as al-Qaeda and other radical Islamist groups.

The newly appointed prosecutors and police chiefs killed the corruption probes and suspended all ongoing investigations into al-Qaeda groups starting in February 2014 at the request of the Erdoğan government. Many of the police chiefs, prosecutors and judges who were involved in al-Qaeda cases were purged and/or imprisoned on bogus charges.