Levent Kenez/Stockholm

Turkey is re-charting its energy future by cutting its reliance on Russian oil, gas and nuclear power as it moves closer to Washington and Brussels, a decisive westward turn driven by new US sanctions and European pressure. For years Turkey insisted it would stay out of Western sanctions due to its reliance on Russian gas and revenue from Russian tourists, but it is now seeking to distance itself from Moscow in energy trade despite not formally implementing the sanctions.

The shift gained momentum after US President Donald Trump imposed sweeping sanctions on Russia’s oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil on October 23. The move followed Trump’s frustration with stalled peace talks with Vladimir Putin and represented the most severe US action against Moscow since the invasion of Ukraine. The sanctions came just days after the European Union adopted its 19th package, targeting Russia’s oil, gas and LNG exports.

Amid this tightening sanctions regime, Turkish refiners began diversifying supply routes. Reuters reported that SOCAR’s STAR Refinery in Turkey and Tüpraş sharply cut Russian crude purchases, replacing them with shipments from Iraq, Kazakhstan and other non-Russian producers. In December alone STAR acquired four cargoes of alternative crude, totaling between 77,000 and 129,000 barrels per day, marking its strongest pivot away from Russian oil in three years.

Behind these trade shifts lies firm diplomatic pressure from Washington. During a White House meeting on September 25, President Trump urged Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to reduce Turkish oil and gas imports from Russia.

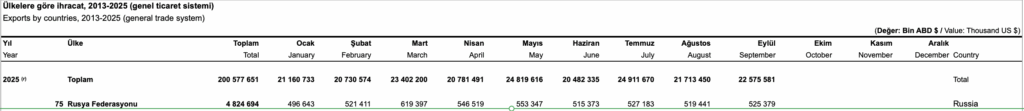

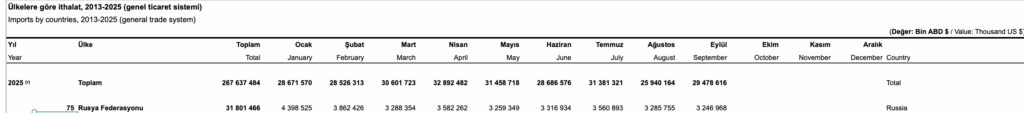

According to figures obtained by Nordic Monitor, Turkey’s imports of Russian products totaled about $31.8 billion between January and September 2025, while exports to Russia reached about $4.8 billion. The monthly value of imports fell from roughly $4.4 billion in January to $3.25 billion in September, signaling a steady contraction in Russia’s share of Turkey’s trade. Analysts view this trend as a key indicator of Ankara’s quiet but deliberate pivot westward.

Turkey’s energy ministry subsequently unveiled a balanced independence strategy, diversifying oil and gas sources, expanding domestic exploration and attracting Western investment in nuclear and renewable energy. The plan aims to bolster national security and restore strategic equilibrium after years of deep reliance on Russian fuel.

Data from market intelligence firm Kpler, cited by Reuters, show that Turkey imported about 669,000 barrels of crude per day between February and October 2025, with 47 percent coming from Russia, down from 57 percent a year earlier. Imports from Iraq rose from 99,000 barrels per day in October, with Ankara now planning to buy 141,000 barrels per day starting in November. Similarly, Russia’s share of Turkey’s gas imports dropped to 37 percent in the first half of 2025, down from more than 60 percent two decades ago.

Nordic Monitor also reported that as Ankara reshapes its oil and gas portfolio, a parallel transformation is underway in nuclear energy, signaling Turkey’s broader strategic realignment. During Erdogan’s visit to Washington, Turkey signed a memorandum of understanding on civilian nuclear cooperation with the United States. Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar confirmed that both the US and South Korea have joined talks for the Sinop Nuclear Power Plant project, effectively sidelining Russia’s Rosatom, which had long been expected to build it. Ankara is reportedly seeking to remove Russia entirely from the Sinop project and award it to US partners, highlighting its determination to loosen Moscow’s grip on Turkey’s energy infrastructure. Had Russia built the second nuclear plant, Turkey would have been entirely dependent on Moscow and under Russian control in nuclear energy. Experts say that even without US pressure, Ankara needed to take this step to reduce that dependence.

Still, the new strategy carries risks. Russia remains Turkey’s top gas supplier via TurkStream, and Rosatom continues to control Akkuyu’s construction and financing. A sudden deterioration in ties could delay projects or disrupt fuel flows.

Earlier, Turkey had benefited from cheap Russian oil and welcomed Russian companies, taking advantage of Moscow’s favor while not joining the Western bloc against Russia. This allowed Ankara to save on oil expenditures and earn revenue during a currency crisis, as the Turkish lira had lost more than 28 percent of its value against the dollar in 2022. President Erdogan even made a controversial statement indicating that Turkey’s doors were open to Russian capital groups seeking to “park” their facilities in the country, a message that appears to have been heeded as Russians led all foreign investors in Turkey in 2022, establishing 1,363 joint ventures — up from just 177 in 2021, primarily in real estate and investment advisory services.

According to a 2023 joint notice from the US Departments of Justice, Commerce and Treasury, malign actors continued to try to evade Russia-related sanctions, often using intermediaries or transshipment points to disguise transactions and obscure the identities of Russian end users.

Erdogan’s turn toward the West is not without domestic motives. Turkey’s opposition argues that President Erdogan is consolidating power by sidelining domestic rivals through imprisonment or pressure, and that maintaining good relations with the US and the EU helps prevent Western criticism over human rights abuses. With the Turkish economy already under strain, any clash with the West could worsen the crisis, trigger a sharp currency depreciation and further exacerbate economic pressures, making Erdogan’s position even more precarious.