Levent Kenez/Stockholm

A confidential document obtained by Nordic Monitor shows that Turkish law enforcement and intelligence agencies have sweeping access to citizens’ private travel, accommodation and communications data, raising concerns about privacy violations and the abuse of counterterrorism laws.

The document, titled Linkage Analysis Report (Birliktelik Analiz Raporu or BAR), was prepared in June by the Branch Directorate for Combating Crimes Against National Security, which operates under the police department. It reveals that authorities are able to query and analyze personal records including hotel reservations, border crossing logs, bus and train tickets and airline passenger data.

According to the report, these datasets are used to draw connections between people who may have no relationship with each other but appear in the same place at the same time. Under Turkish law, however, such information is considered part of private life and is legally protected. Both the Turkish Penal Code and the Law on the Protection of Personal Data prohibit the collection, use or disclosure of travel and accommodation details without an individual’s consent. Violations may constitute a criminal offense.

The document demonstrates that in practice these safeguards are circumvented by giving police and intelligence services unrestricted access to nationwide databases.

The BAR document indicates that much of this investigative method has been directed at followers of the Gülen movement, a religious and social group inspired by the late cleric Fethullah Gülen. The movement has been a target of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan since 2013, when corruption investigations implicated him and members of his inner circle. The government accuses the movement of orchestrating a coup attempt in 2016, an allegation the group denies. The government’s unilateral designation of the group as a terrorist organization is not formally recognized internationally, a reluctance widely attributed to the belief among global actors that the label is politically motivated rather than based on independently verifiable evidence

The report shows that police query whether individuals have used a messaging application called ByLock and, if so, with whom they communicated. Turkish courts have long deemed downloading ByLock, which they claim was used by members of the Gülen movement, as sufficient evidence for membership in a terrorist organization. Regardless of its content, the use of the application itself has been treated as incriminating. ByLock was publicly available on Google Play, yet Turkish authorities have presented it as a clandestine tool.

In a landmark ruling with potentially far-reaching implications, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights decided in the Yalcinkaya case in September 2023 that mere possession of the ByLock application cannot constitute evidence of terrorism.

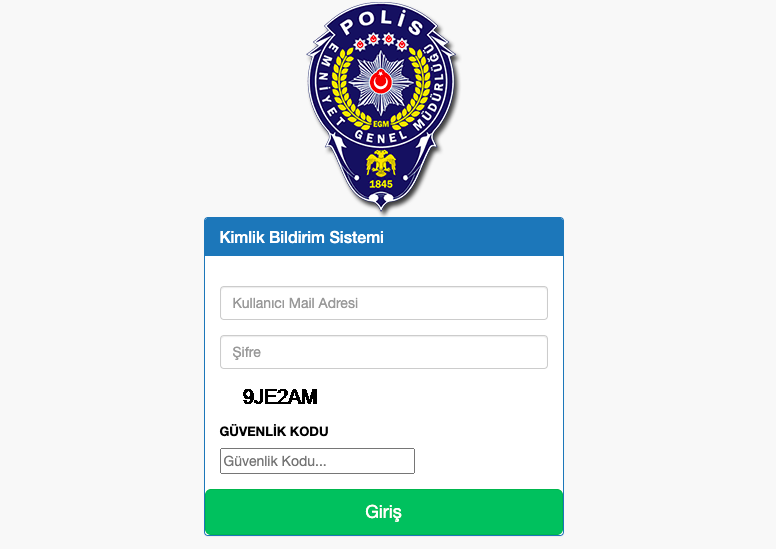

According to a report obtained by Nordic Monitor, Turkish police have unrestricted access to multiple databases containing private information. Personal data have been redacted for security reasons:

The document also specifies that hotel and guesthouse records are gathered through a system operated by the public order department of the police, with data supplied directly by accommodation providers across the country. Border gate authorities feed in entry and exit records, which can be cross-referenced to show individuals passing through the same checkpoint within a 30-minute window. Airline passenger manifests are supplied in the form of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Records by carriers, allowing police to identify travelers on the same flights as targeted individuals. Bus companies upload journey records to a database run by the information technologies department and available to the police, and the State Railways delivers train passenger lists showing who boarded and disembarked at the same points.

By combining these categories, police produce what the report calls “linkage analyses,” intended to establish whether a suspect was accompanied by others considered suspicious. The scope of access described in the document indicates that virtually all forms of movement inside and outside the country are tracked and readily available to investigators.

The practice has already resulted in citizens being interrogated about strangers they happened to encounter in hotels or on the same trip. Detainees have been asked to explain why they stayed in the same hotel as another suspect or why their phones connected to the same cell tower in the past, despite the fact that such coincidences are common in urban areas and do not necessarily indicate personal contact.

Police records also show that similar data analyses have been applied in counterterrorism cases in which suspects were linked solely on the basis of shared travel patterns or overlapping HTS, or Historical Traffic Search, logs. HTS data, obtained from mobile phone operators, registers call records and the locations of cell towers. Human rights lawyers have long argued that using HTS matches as evidence of association is unreliable, but courts in Turkey continue to accept such records as grounds for prosecution.

Nordic Monitor previously reported that police interrogations often include questions about hotel stays, asking suspects why they were in the same establishment as people accused of Gülen ties. In one instance an Istanbul court in 2019 ordered investigators to review hotel records to see whether journalists from the leftist Birgun newspaper had stayed at the same hotel as Gülen-affiliated individuals. In another example the indictment of jailed businessman Osman Kavala referred to phone records showing his and US academic Henri Barkey’s devices connected to the same cell towers on several occasions. Barkey dismissed the claim, pointing out that in crowded cities such overlaps are inevitable and meaningless.

Statistics underscore the scale of Turkey’s use of counterterrorism laws. The Council of Europe reported in 2022 that 95 percent of people imprisoned for terrorism in Europe were in Turkish prisons, a figure rights groups say illustrates Ankara’s tendency to label critics and opponents as terrorists.

The practice has led to secret files that follow citizens even when they apply for government jobs. Security clearances are conducted against these records, meaning that people may be excluded from employment opportunities based on data linking them to suspects, even when no charges have been filed.

Beyond counterterrorism cases, misuse of these databases has also been documented. Nordic Monitor previously learned that some police officers accepted bribes to provide access to hotel records. Suspicious spouses were able to check whether their partners had stayed in hotels with other individuals by paying officers who had entry into the ID reporting system. Although in principle such unauthorized searches can be traced, officers reportedly justified them as part of terrorism inquiries, making accountability difficult.

The wide application of HTS data also appeared in recent political cases. In March Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, the main opposition’s presidential candidate, and scores of city officials were arrested as part of a corruption and bribery investigation. Prosecutors cited HTS records that placed their phones near those of other suspects, using the data to support accusations. Imamoglu, who has remained in detention since March 19, denies any wrongdoing and says the charges are politically motivated. Analysts note that many defendants in the case argued that connecting to the same tower in crowded districts is routine, but courts nevertheless accepted the evidence.