Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

A meeting between notorious mob boss Alaattin Çakıcı and Ogün Samast, the convicted murderer of Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink — both of whom were released early with the help of the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan — epitomizes the current state of governance in Turkey, where killers and mafia figures are used to sustain a climate of fear and impunity aimed at suppressing dissent and intimidating opponents, journalists and activists.

Çakıcı, who was given the authority by the Erdogan government to manage organized crime groups involved in activities such as drug trafficking in Turkey and northern Cyprus, met with Samast in November 2024 during a tour of the Black Sea region. They held their meeting at a hotel in the northeastern province of Trabzon and later traveled together to the Georgian border.

Photos and video footage from the meeting showed Samast addressing Çakıcı as amca (uncle) and kissing his hand — both symbolic gestures that convey reverence, respect and allegiance. The meeting suggests that Samast is now under the protection of the notorious mob boss, who maintains close ties to the Erdogan government and its far-right partner, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

The spectacle reinforces longstanding allegations that powerful elements within Turkey’s security establishment — shielded by political and legal protection — were complicit in orchestrating the 2007 assassination of journalist Dink, targeted for his critical views and his efforts to foster Turkish-Armenian reconciliation.

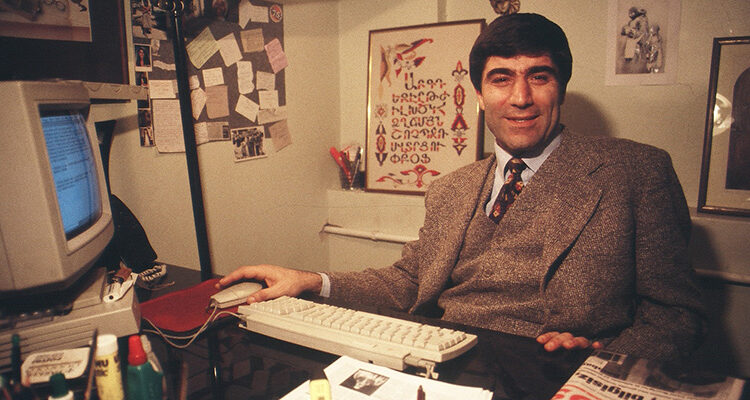

Dink was systematically targeted by both nationalist (milliyetçi) and neo-nationalist (ulusalcı) networks in Turkey. He was defamed through hostile media coverage and faced criminal charges from Turkish authorities for allegedly insulting the state in his articles. His persecution was part of a broader campaign in Turkey at the time — one sanctioned by the National Security Council (Milli Güvenlik Kurulu), a shadowy institution that functions as the true guardian of the country’s authoritarian core.

Turkish intelligence agency, MIT (Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı), played a key role in fostering the events that led to the journalist’s murder. Yet, after nearly two decades of legal battles, the government still protects the agency from any criminal accountability. MIT feigned ignorance in response to court requests for information related to the period before and after Dink’s assassination.

Dink was privately threatened by MIT, and the Istanbul Governor’s Office denied him police protection, leaving him ultimately vulnerable to attacks despite clear, immediate and credible threats of murder and violence. Neither the officials from the governor’s office nor the MIT officers involved in threatening him were ever investigated.

Turkish prosecutors limited their efforts to merely taking depositions from Deputy Governor Ergun Güngör, who participated in a 2004 meeting at the Istanbul Governor’s Office during which Dink was threatened, as well as MIT’s Istanbul Regional Directorate officer Özel Yılmaz. Ultimately, the prosecutors issued a decision of non-prosecution, effectively shielding both officials from any criminal liability.

Samast, then a minor, was manipulated and nurtured as the gunman in Dink’s assassination. He was supplied with a gun, logistical support and intelligence to carry out the assassination in an Istanbul neighborhood where he was not known. After his arrest, police officers in Samsun province treated him like a hero, posing for photos with him in front of a Turkish flag. The gendarmerie intelligence network alleged to have supported and facilitated the murder was never thoroughly investigated. In the end, the true masterminds who ordered the assassination were never identified.

In multiple testimonies over the years, including one on March 6, 2024, Samast stated that his co-conspirators — Yasin Hayal and Erhan Tuncel — were both known to Turkish authorities, with Tuncel even serving as an informant for police intelligence. Samast said they repeatedly assured him that the Turkish state was behind him and that he had nothing to fear from the consequences of the murder.

The Turkish government shielded Engin Dinç, who was head of police intelligence in Trabzon, the city where Samast lived and was radicalized. Court documents revealed that it was Dinç who recruited Tuncel as an informant, met with him frequently in his office and built a close relationship with the man who inspired the journalist’s murder. Not only was Dinç never held accountable, he was also rewarded by President Erdogan, who later appointed him as director of the National Police Department’s intelligence unit. He currently serves as the chief of the Ankara Police Department.

Samast’s judicial record is equally alarming. He was sentenced to 21-and-a-half years for the murder, along with an additional one year, four months for carrying an illegal weapon. While in prison, he committed further crimes, attacking guards with a contraband knife he had hidden in his cell and injuring two officers in January 2017. For these offenses, he received an additional five-year sentence.

When authorities decided to release Samast in November 2023, they justified the decision by citing his alleged good behavior in prison, his perceived ability to reintegrate into society and his eligibility for early release. In reality, Samast still had six years of his sentence left to serve. While Turkish authorities routinely deny similar leniency to political prisoners and wrongfully convicted journalists, a convicted murderer and violent inmate was granted preferential treatment and released early.

Another pending case against Samast, involving charges of membership in an armed group, was effectively nullified when the Supreme Court of Appeals ruled that the statute of limitations had expired. This outcome suggests that Samast enjoyed protection from powerful figures within the Turkish government, enabling his early release precisely when those behind the murder deemed the timing favorable.

A similar tactic was used to secure Çakıcı’s release from prison in 2020, despite his facing a lengthy sentence for multiple crimes, including murders committed as a notorious mafia leader. Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the MHP and Çakıcı’s political protector, hailed him as a patriot and justified his actions as part of state duties.

Dink’s murder did not occur in a vacuum. It was the result of a deliberate witch hunt and nationalist fervor, deliberately stoked by state actors, that created the environment for his assassination. Systematic efforts by Turkey’s National Security Council in the early 2000s to amplify anti-minority sentiment as part of a broader nationalist agenda played a significant role in paving the way for the journalist’s tragic demise.

Erdogan’s government has not only shielded the perpetrators but also exploited Dink’s murder as a tool for political vendettas — particularly targeting the Gülen movement, which it accuses of orchestrating nearly every major scandal and crime in modern Turkish history. Despite the absence of any credible evidence linking the movement to the Dink case, it continues to serve as a convenient scapegoat in official narratives.

The lawyers representing the Dink family maintain that the authorities failed to conduct an effective investigation into the events leading up to Hrant Dink’s murder. In a petition submitted to the Supreme Court of Appeals in June 2022, they stated: “The events leading up to Hrant Dink’s murder were not thoroughly investigated, nor were those who organized and carried out the lynching campaign against him. The investigation did not dig deep enough to uncover the connections between those involved in the lead-up and the murder itself.”

Moreover, Turkish judicial authorities chose not to prosecute neo-nationalist figures such as Veli Küçük, Kemal Kerinçsiz and Oktay Yıldırım, who were among those organizing the lynching campaign against Dink. The lawyers challenged the decision of non-prosecution, but their efforts were unsuccessful. These individuals, who were tried and convicted on various criminal charges between 2008 and 2012, were all released from prison in 2014 following political interference and a secret alliance forged between Erdogan and the neo-nationalist network known as Ulusalcılar.

Some officials implicated in the conspiracy to murder the journalist received explicit protection from the government. When Dink’s lawyers petitioned the Istanbul 14th High Criminal Court to summon MIT agents to testify as witnesses in September 2020, the court rejected the request.

Similarly, an investigation into the Office of the Chief of General Staff — which issued a harsh statement against Dink in February 2004, fueling the lynching campaign against him — was also quashed by Turkish authorities. In September 2020 Dink’s lawyers petitioned the court to investigate who in the General Staff contacted the MIT chief to threaten Dink during a meeting at the Istanbul governor’s office in 2004, the reasons behind requesting such a meeting and its intended purpose. However, the court rejected this petition as well.

In the end, the government curtailed the court cases related to the journalist’s murder, prevented the true masterminds from being exposed and shielded the military, police and intelligence agencies from legal accountability, all while exploiting the case to blame unrelated groups and individuals. As a result, justice was never served, and accountability has remained an elusive goal.

Meanwhile, Turkey remains a country where journalists — even foreign reporters — face relentless oppression and crackdowns, including imprisonment and fabricated criminal charges under Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian regime.