Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

A letter from Turkey’s interior minister has exposed how the country has become a safe haven for organized crime networks, drug traffickers, cybercriminals and internationally wanted fugitives.

Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya, who oversees the country’s two main law enforcement agencies — the police and the gendarmerie — claimed in a letter to parliament that more than 660 organized crime groups operating in Turkey had been dismantled over the past year.

While the minister sought to highlight the government’s crackdown on criminal networks, he inadvertently acknowledged that authorities had for years allowed such groups to operate freely in Turkey, neglected their activities and failed to take an action until recently.

According to the letter, a copy of which was obtained by Nordic Monitor, between June 2023 and August 2024, Turkish authorities conducted over 1,600 operations, detaining 11,635 people and formally arresting more than 4,500.

Yerlikaya failed to provide figures on how many of those arrested were ultimately convicted since most arrestees are released at their first hearing and acquittals are the most common outcome at the end of trials, largely due to the political connections cultivated by organized crime groups in Turkey and the judiciary’s subordination to the executive branch.

On paper, the letter reads like a victory. In reality, it raises a deeper question: Why were these sprawling criminal empires allowed to take root and operate so freely in the first place? And why the delayed action, especially when multiple countries had long urged Turkey to dismantle groups that threatened public order and national security beyond its borders?

A letter written by Turkish Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya exposed how organized crime groups have flourished in Turkey in recent years:

The most damning revelation is the sheer scale of the criminal landscape — 660 separate organizations, each with its own network of operatives, financial infrastructure, weapons, political ties and significant assets. Notably, this figure covers only a 14-month period, as the minister did not disclose how many organized crime groups had been targeted in previous years or after October 30, 2024, the date the letter was signed.

However, the minister frequently posts messages on his X account, claiming that the police dismantle dozens of organized crime networks each week, bringing the total far beyond what he reported in his official letter. Critics argue that the government often targets low-level figures in criminal enterprises while avoiding the masterminds who orchestrate the schemes.

These groups were not only well-equipped but deeply embedded in Turkish society. Such a presence doesn’t materialize overnight. These groups didn’t operate in the shadows, but in plain sight — under the watchful eye of law enforcement agencies that appeared unwilling to intervene against such groups, often deterred by political signals from the government.

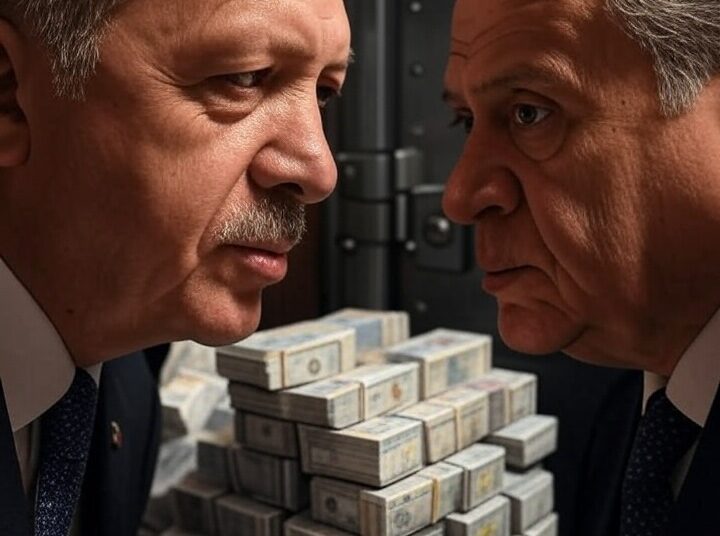

This naturally raises serious concerns about the integrity of Turkey’s judiciary and law enforcement and intelligence agencies — institutions that have become deeply politicized under the Islamist government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and its far-right nationalist ally, Devlet Bahçeli, who has been described as the godfather of mafia groups and criminal enterprises in Turkey. The government’s prolonged inaction in dismantling hundreds of criminal syndicates suggests not only a troubling complicity but also a glaring lack of political will to confront these networks.

Among the thousands of items confiscated in the 2023-2024 operations were 545 long-barreled weapons, nearly 10,000 handguns and 19 hand grenades — military-grade firepower on civilian streets. Add to this the massive haul of drugs, counterfeit documents and over 6,000 promissory notes used for financial coercion, and a clear picture emerges: This wasn’t just criminal behavior; it was organized, armed, and thriving under the rule of President Erdogan.

The widespread use of fake identities and the infiltration of public institutions — an issue the ministry acknowledged — further suggests that organized crime in Turkey isn’t just a policing problem. It’s a state vulnerability.

While Minister Yerlikaya emphasized that “even public officials” are not exempt from investigation, the very need for such a statement exposes a deeper systemic rot. If public servants were involved — and mounting evidence suggests many were — then where were the oversight mechanisms? Where was the accountability? The minister did not disclose how many officials were investigated, arrested or prosecuted in connection with their ties to these organized crime groups.

The problem extends beyond homegrown organized crime syndicates. Over the past decade, Turkey has become a haven for notorious international criminals, some of whom have even been granted Turkish citizenship and political protection.

The letter states that between June 2023 and August 2024, 552 fugitives wanted by INTERPOL were arrested in Turkey. That such a large number of international criminals could operate — or hide — in the country raises serious concerns about border security and international cooperation. How did Turkey become a safe haven for so many fugitives in the first place?

The opposition claims that financial incentives have driven the Erdogan government to allow Turkey to become a hub for international criminal groups. According to lawmaker Cevdet Akay, a total of $76.7 billion in funds of unidentified origin have been injected into the Turkish economy during Erdogan’s two decades in power. In contrast, the same figure stood at just $1.7 billion between 1984 and 2001.

Erdogan and his associates are accused of benefiting from criminal groups that pay protection money and bribes to Turkish officials in order to avoid legal troubles while operating from within Turkey. Mehmet Ağar, a former interior minister who is believed to wield significant influence over the country’s police apparatus, is frequently identified as the key figure coordinating various organized crime activities on behalf of the Erdogan government.

The case of Cemil Önal, who worked as a bookkeeper for the Falyalı criminal enterprise from 2014 to 2021 and was recently murdered, illustrates how organized crime in Turkey has been facilitated. Önal played a key role in establishing a large-scale money laundering scheme that moved illicit funds out of northern Cyprus, which is controlled by Turkey.

He revealed in detail how former interior minister Süleyman Soylu and former vice president Fuat Oktay accepted millions in bribes, and that compromising tapes involving Erdogan’s son Burak and Erkam Yıldırım, son of former prime minister Binali Yıldırım, were used as leverage by the Falyalı group. Önal also shared audio recordings of his conversations with members of the Turkish judiciary, during which they discussed bribes in exchange for dismissing criminal cases against the group. Önal’s allegations were never investigated in Turkey. He was assassinated on May 1, killed in the bar of the hotel where he was staying in The Hague.

Önal’s case is not an isolated incident, but rather the latest addition to a long list of criminal groups operating in Turkey, paying protection money to government officials — with the lion’s share going to President Erdogan and his far-right nationalist allies.

The government typically takes action against internationally wanted criminals only when external pressure becomes unbearable for the Erdogan administration and the disadvantages outweigh the benefits. Even in these cases, Turkish connections are often overlooked, and local networks that enable foreign fugitives to sustain their operations within Turkey remain untouched. These limited operations also serve to help Erdogan deflect criticism both at home and abroad.

This climate of impunity appears deeply entrenched, as organized groups continue to flourish while authorities often target street-level operatives rather than the leadership or true masterminds in police operations.

The government’s attempt to frame these operations as a resounding success rings hollow in light of what they reveal: For years, criminal syndicates have operated with impunity, building networks of violence, intimidation and illicit finance in Turkey’s cities and institutions.