Levent Kenez/Stockholm

Turkey is strengthening its bid to host major international meetings as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan places growing priority on high-visibility global gatherings that allow him to appear alongside world leaders. This practice, which could be described as ‘hosting diplomacy,’ has become a defining element of Turkey’s foreign policy at a time when other countries often hesitate to take on the financial and logistical burden of such summits. The fact that Turkey, with its poor record on democracy and human rights, receives support from the West is also criticized by opposition groups in the country.

The strategy coincides with Erdogan’s longstanding emphasis on international visibility. His attendance at G20 summits and the United Nations General Assembly every September has been a consistent feature of his schedule, despite chronic health issues and periods of mental disengagement. Turkish officials regularly frame these events as essential moments for the president to engage directly with global leaders. Critics in Turkey argue that the gatherings help Erdogan reinforce the image of a powerful leader who maintains international legitimacy despite concerns about democratic backsliding at home. Turkish foreign policy is increasingly used as a tool for international recognition by a government facing political tension and economic strain.

Erdogan’s Communications Directorate and the pro-government media play a central role in amplifying Erdogan’s international appearances. The directorate frequently publishes social media images featuring Erdogan with heads of state or leaders he meets during global events. The images depict steady lines of presidents and prime ministers greeting him, which supporters view as evidence of Turkey’s global relevance.

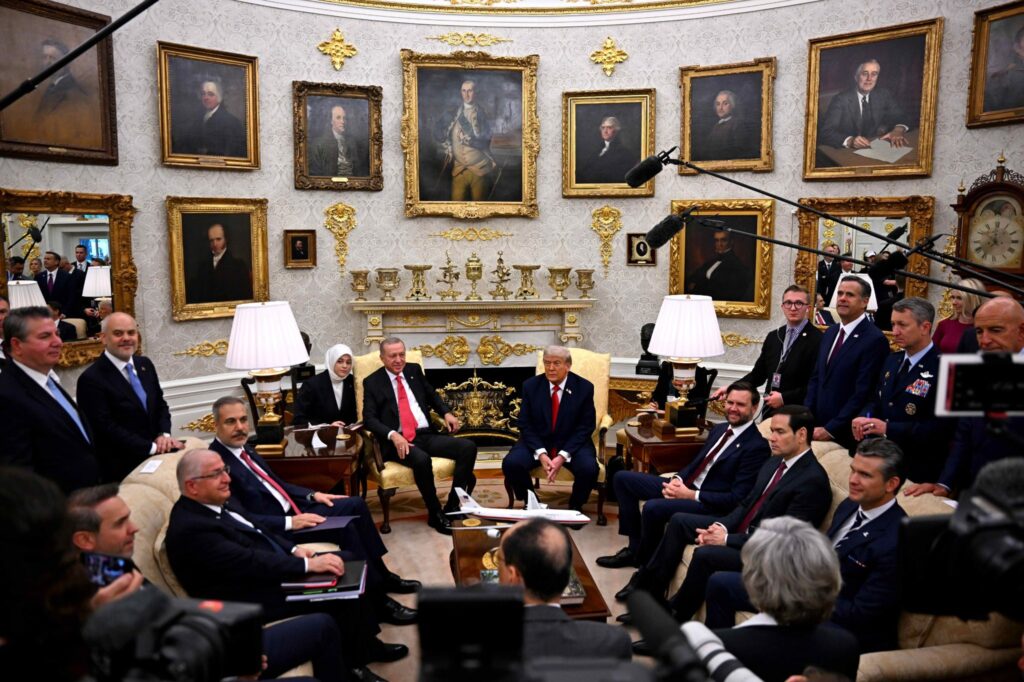

Being received at the White House has long been one of the appearances Erdogan values most in foreign policy, a tradition that dates back to his meetings with former United States presidents including George W. Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump. During Joe Biden’s presidency the White House did not grant Erdogan an official Oval Office meeting, a fact that generated persistent discomfort in Ankara. Turkish officials noted privately that the absence of a bilateral visit broke with the pattern of regular high-level encounters between Turkish and American leaders. The lack of a White House invitation stood out given Erdogan’s previous meetings in Washington and became a repeated point of irritation for the government during a period of tense relations over defense cooperation, sanctions and regional policy differences.

The question of legitimacy surfaced in international discussions when US Special Representative for Syria and Ambassador to Turkey Tom Barrack said during the Concordia Summit on September 24, 2025, that President Trump aimed to provide Erdogan with the legitimacy he sought. He linked that view to years of strained ties between Turkey and Western governments, with his remarks sparking criticism in Turkey and reviving the debate over Ankara’s efforts to gain recognition on the global stage. Opposition parties criticized Ankara’s silence in response to Barrack’s comments, saying it was humiliating for the country to appear to confer legitimacy on the president.

Turkey’s willingness to assume hosting duties for costly international events has set it apart from other governments that prefer to avoid the expense. The most recent example is the decision to hold the COP31 climate summit in Turkey next year. The outcome followed a prolonged standoff between Ankara and Canberra over the location of the conference. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced that Australia would lead negotiations with Pacific Island nations ahead of the 2026 meeting, while Turkey would assume the presidency of COP31. He said the arrangement offered a positive result for both countries.

The selection prompted questions about Turkey’s environmental record. Environmentalists in Turkey said the decision was ironic given the country’s limited history of environmental sensitivity. Climate activists pointed to the gap between Turkey’s ambition to host COP31 and its domestic record on emissions, coal reliance and climate policy implementation.

Ankara has embraced additional high-profile events. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte announced that the 2026 NATO summit would be held in on July 7 and 8 at the presidential palace in Ankara . Turkey had volunteered to host the summit even though several member states have not yet held one. It will be the second time Turkey hosts the alliance after the 2004 meeting in Istanbul.

Turkey will also host the International Astronautical Congress in 2026. Istanbul’s Beşiktaş Park stadium will stage the 2026 UEFA Europa League final next May. Antalya continues preparations for upcoming editions of the Antalya Diplomacy Forum, a gathering launched in 2021 that has attracted global attention. The forum hosted Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba in March 2022 for their first in-person meeting after the outbreak of the war.

While organizing these events, Turkey has faced scrutiny over past commitments. One example frequently cited by women’s rights groups is Ankara’s role in promoting a global summit on preventing violence against women. Turkey played a major role in the creation of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, which became known as the Istanbul Convention because it was opened for signature in Istanbul in 2011. Despite championing the treaty, Turkey withdrew from it in 2021 through a presidential decree. The government said parts of the convention conflicted with social values. Women’s rights groups condemned the move and said the withdrawal amounted to a reversal of earlier commitments. European institutions expressed regret over the decision. Opposition figures argued that international agreements come into force only with parliamentary approval and cannot be invalidated solely by a unilateral presidential decree. Nevertheless, Erdogan issued the decision ahead of elections, aiming to secure the support of the conservative Welfare Party. Critics noted that, given that the judiciary and other institutions are largely under Erdogan’s control, the country’s formal status in the convention carried little practical significance, a situation sometimes likened to France’s handling of the Paris climate agreement.

Political tension inside Turkey continues to frame the debate over Erdogan’s international outreach. Human rights groups have criticized the government for prosecuting opponents and detaining local officials. Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoglu has been held in pretrial detention since March, prompting widespread protests.

Turkey’s international summit ambitions sharply contrast with its weak performance on global governance and rights benchmarks. According to the World Justice Project’s 2025 Rule of Law Index, Turkey ranks 118th out of 143 countries, signaling a persistent erosion in judicial independence, government checks and fundamental rights. In press freedom Reporters Without Borders puts Turkey in 159th place out of 180, citing state control over media, politically motivated prosecutions and severe censorship. The Economist Intelligence Unit classifies Turkey as a hybrid regime, pointing out declines in civil liberties and democratic governance. Freedom House describes Turkey as “Not Free,” noting shrinking political rights, restricted civil liberties and limits on internet freedom, including surveillance and online censorship.