Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

A belated investigation by Turkish authorities into a sprawling drug trafficking syndicate stretching from Iran to Western Europe has exposed how an Iranian trafficker acquired Turkish citizenship with apparent ease and emerged as a central figure in an international crime network.

The case, largely built on intelligence shared by European law enforcement, reveals a web of traffickers who for years used Turkey as a strategic hub to channel heroin into European markets via Russia and the Balkans.

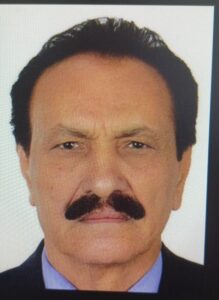

At the center is Amir Alizadeh, an Iranian national who became known as Nihat Yılmaz after naturalization. Investigators allege that Alizadeh supplied hundreds of kilograms of heroin to the syndicate and laundered the proceeds through property acquisitions and business fronts, embedding himself in Turkey’s financial and legal system as a citizen.

According to prosecutors, the group’s main route ran through Central Asia into Russia, concealing heroin in commercial fruit shipments before moving the drugs across Poland into the Netherlands. In one major operation 784 kilograms of heroin originating in Iran were hidden in four fruit-laden trucks. Russian authorities intercepted 370 kilograms, but 414 kilograms still reached the European market.

That shipment was organized by Iranian trafficker Jelal Salimi Anbi together with Turkish nationals Musa Tahiroğlu and his son Murat Tahiroğlu, routed through Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan before entering Russia. Storage was overseen by Özgür Bedir, a Turkish citizen, while distribution in the Netherlands was coordinated by another Turk, Abdullah Kavçan.

The syndicate’s financial and legal façade was facilitated by prominent Turkish lawyer Osman Mercan and his associates Veysi Gündoğan and Ercan Polat, who set up shell companies to disguise shipments as legitimate business.

The partial interception in Moscow led to the arrest of Bedir and another Turk, Hüsni Coşar. Russian investigators identified the ringleaders as İbrahim Kurtar and his son Sezgin Kurtar, operating along with family members Kamuran Kurtar, Ömer Faruk Kurtar, Uğur Kurtar, Zeki Kurtar and Fatih Bedir and Iranian trafficker Salimi Anbi.

Other consignments included 890 kilograms and 372 kilograms of heroin, originating in Iran’s Mashhad region, staged through Moscow warehouses before being dispersed across Europe. These shipments were coordinated jointly by Kurtar and Anbi. In another case, 372 kilograms were moved through Russia into several European countries under Kurtar’s direction, with Turkish trafficker Muharrem Ayhan assigned to oversee the transportation. He was instructed to hire Bulgarian trucks and drivers to move the consignment out of Moscow.

The network also trafficked cocaine from Colombia to Western Europe, using varied routes.

A decisive breakthrough came from the dismantling of the SKY-ECC encrypted communication network, widely used by organized crime groups. Decrypted messages exposed supply negotiations, laundering strategies and exchanges placing Alizadeh directly in procurement and distribution. At one point he allegedly delivered 200 kilograms of heroin and, under pressure from Kurtar, attempted to secure a further 300 kilograms. Only 145 kilograms ultimately reached the network due to logistical setbacks.

The indictment drafted by Istanbul prosecutors names 42 defendants, including traffickers, businessmen and a lawyer accused of creating front companies to disguise shipments and launder profits. Authorities seized assets worth hundreds of millions of lira, freezing companies in construction, tourism, automotives and finance.

Among the confiscated companies are Kurtar Otomotiv (auto sales), Lior Turizm ve Otelcilik (hospitality), Friends Finansal Danışmanlık AŞ (financial consulting) and Zoraoğlu İnşaat Turizm AŞ (construction and tourism).

The probe has not only revealed the syndicate’s logistical sophistication but also raised serious questions about Turkey’s complicity in global drug trafficking and the systemic loopholes that allowed criminals to exploit pathways to citizenship, weak oversight and real estate markets to conceal their operations.

Investigators noted that the group relied heavily on Sky-ECC, which was dismantled in 2021 after European law enforcement cracked its encryption in 2020–2021. Yet Turkish authorities waited until June 8, 2024 to launch their operation against Alizadeh and his Turkish partners. Critics argue this delay gave the syndicate time to cut losses and allowed senior figures to escape. They stress that Alizadeh’s close engagement with convicted Turkish traffickers should have raised red flags years earlier, even without the Sky-ECC intelligence.

In intercepted messages, Turkish national Cengiz Yılmaz was recorded transferring heroin and cocaine proceeds to Sezgin Kurtar in Turkey through hawala, an informal system for transferring money through brokers without using banks.

The Istanbul 19th High Criminal Court has accepted the indictment, with the trial set to start later this month. Of the 42 defendants, 13 are in pretrial detention — including Kavçan, Alizadeh, Yılmaz, Engin Salcan, Polat, İbrahim Kurtar, Ayhan, Murat Tahiroğlu, Mercan, Ömer Faruk Bazancir, Sedat Hepgüler, Sezgin Kurtar, and Gündoğan — while 11 are fugitives and the remainder will stand trial without detention.

The case illustrates how international syndicates exploit weak governance structures, naturalization policies, informal banking and real estate markets to safeguard vast drug empires, leaving Turkey both a facilitator and a beneficiary of Europe’s narcotics trade.

Alizadeh is not the only Iranian who has acquired Turkish citizenship and adopted a Turkish identity in recent years. Over the past decade, thousands of Iranians have been naturalized under the Islamist government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, including individuals with extensive criminal backgrounds.

Among the most notorious figures is Reza Zarrab, who laundered billions of dollars in Iranian state funds through Turkish banks under the guise of legitimate trade. He bribed senior Turkish officials, including three cabinet ministers and President Erdogan himself.

Zarrab was first arrested by Turkish police in December 2013, but Ergogan intervened to secure his release and quash the corruption investigations. Several years later he was detained by the FBI in Miami, indicted by US federal prosecutors and eventually agreed to cooperate as a government witness. In US court he provided explosive testimony implicating Erdogan’s direct involvement and exposing the scale of corruption among Turkey’s political elite.