Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Amid rising authoritarianism and xenophobia under President Recep Tayyipp Erdogan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), Turkey’s intelligence agency, Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı (MIT), has stepped up its repression of the country’s Christian population.

Motivated by political Islamist ideology, the Erdogan government’s systematic profiling of unsuspecting Christians has upended the lives of law-abiding foreign nationals — many of whom had lived in Turkey for decades — forcing them out of the country and, in some instances, barring their return

One striking example of this persecution is Hans-Jürgen Peter Louven, a 64-year-old German biology and sports teacher who moved to Turkey in 1994 with his Austrian wife Renate and their one-year-old daughter Hanna. For more than two decades, the family lived peacefully without any legal or immigration issues, until the summer of 2019, when Turkish authorities abruptly decided not to renew their residence permits.

That decision turned the Louven family’s lives upside down, forcing them to leave the country where they had established roots, retired, engaged in community and faith-related work and raised their daughter.

It was later revealed that behind this immigration decision was a secret report prepared by Turkish intelligence, which labeled Louven, a God-fearing Christian man, as a national security risk.

The MIT’s report on Louven prompted Turkey’s Migration Management Authority (Göç İdaresi Başkanlığı, GIB), under the Interior Ministry, to assign him the code N-82, marking him as a security risk comparable to terrorists such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Turkey’s Constitutional Court deferred to Turkish intelligence’s secret report in justifying the denial of the Louven family’s residence permit, failing to deliver justice to the victims:

No solid evidence implicating Louven in any activity that might pose a threat to the country was ever presented by Turkish authorities during the ensuing five-year legal battles, which involved both local courts and the Constitutional Court.

However, the secret MIT report alleging Christian missionary work is believed to be the primary reason the immigration agency refused to renew his residence permit.

Louven maintains that he was never involved in missionary work but never concealed his religious identity. He openly shared his faith with locals for years, contributed to volunteer activities, and promoted faith-based tourism around historic landmarks in western Turkey. He believes that his participation in a conference organized by a Protestant church in Antalya led MIT to wrongly profile him as engaging in activities deemed threatening to public order and national security.

Missionary work is not criminalized under the Turkish Penal Code, and the Turkish Constitution guarantees freedom of religion. Yet in practice, Turkish authorities often treat such activities as threats, viewing members of minority faiths with suspicion. Meanwhile, Turkish media — largely controlled by the government — frequently runs negative campaigns against these groups, portraying them as a fifth column intent on undermining Turkey’s security.

In court filings challenging the migration agency’s decision, Louven denied any wrongdoing, emphasizing that he had never been charged with or investigated for any crime during his more than 20 years in Turkey. He argued that the vague allegations based solely on classified intelligence violated his rights to family life, religious freedom and a fair trial.

Louven and his wife built a life in Turkey’s resort province of Muğla, establishing businesses in the tourism industry and helping to attract many visitors to the region. They raised a daughter who attended public schools and came to love the country and its people, cherishing its historical and cultural richness. Their contributions to the local community were even recognized by the provincial governor.

However, the legal challenge to the migration agency’s decision to deny residence permit renewal was rejected in February 2020 by the Muğla Administrative Court, which cited national security concerns raised by the intelligence agency as justification. This ruling was later upheld on appeal by the İzmir Regional Administrative Court.

The courts determined that the government had a legitimate interest in protecting national security and that the intelligence-based assessment provided sufficient grounds to deny the residence request. The MIT report remained confidential throughout the judicial process and allegedly linked Louven to unspecified missionary activities without detailing any specific acts or evidence.

Louven escalated the case to the Constitutional Court, alleging violations of his rights to family life and religious freedom, both protected under the Turkish Constitution. He also argued that his right to a fair trial was breached because the alleged evidence against him was never fully disclosed during the proceedings in the lower courts.

However, the Constitutional Court, stacked with judges loyal to President Erdogan, ruled on October 24, 2024, that no violation had occurred, effectively disregarding the binding provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) in Turkey.

Although the Constitutional Court acknowledged that the applicant’s right to family life had been interfered with, it nevertheless ruled that the interference was lawful, pursued a legitimate aim and struck a fair balance between public interest and individual rights

The ruling emphasized that states possess broad discretionary powers under international law to regulate the entry and residence of foreign nationals, particularly when national security concerns are involved.

On the issue of religious freedom related to Louven’s participation in a Protestant church conference in Antalya, the court found no violation, ruling that missionary activity may lawfully be restricted when believed to threaten public order. The judges emphasized that although missionary work itself is not criminalized in Turkey, intelligence assessments linking such activity to national security threats can justify administrative action.

Turkish courts aligning with the intelligence agency — which operates behind a thick veil of secrecy, without accountability or effective oversight from judicial or legislative bodies — comes as no surprise. The Erdogan government depends heavily on the intelligence agency to sustain its repressive regime, often exploiting xenophobia to stoke fear among the Turkish population.

The main motivation behind the policy of making life difficult for Christians in Turkey stems from an entrenched political Islamist ideology that harbors deep animosity toward non-Muslim minorities as well as Muslim groups like the Gülen movement, which opposes the exploitation of faith for political ends.

The Erdogan government deliberately stokes fear of Christians and Jews among Turkey’s predominantly Sunni Muslim population of 86 million to consolidate its support, silence critics and distract voters from pressing issues such as economic hardship and financial struggles.

As a result minority ethnic and religious communities, along with groups critical of the Erdogan government, are often victimized as enemies of the state. Turkish intelligence actively profiles hundreds of thousands of Turkish and foreign nationals as security risks, despite lacking any evidence of criminal activity to justify such actions.

Louven and his family’s harrowing saga underscores how Turkish authorities grant substantial deference to intelligence reports that remain shielded from public and judicial scrutiny. Critics argue that the use of vague, unverifiable allegations by MIT, an agency operating with total impunity and lacking transparency and accountability, severely limits individuals’ ability to mount an effective legal defense.

Turkish court rulings illustrate how intelligence assessments can undermine due process and override human rights protections, especially in cases involving foreign nationals and groups critical of the Erdogan government.

Louven first arrived in Turkey’s Antalya province in 1994 and settled in Muğla province in 1998. He began his business restoring historic homes for tourism purposes as a representative of CRG Reisen, a Christian non-profit travel organization based in Germany and affiliated with the Freie Brüdergemeinden (Free Brethren Churches).

In 2004, Louven and two partners — German national Peter Dieter Maletzki and Turkish national Macit Pekicten — founded a multi-purpose company named AGAPE Turizm İnşaat Özel Eğitim Hizmetleri Gıda Pazarlama Ticareti İthalat ve İhracat Limited Şirketi in Muğla, focusing on faith-based and cultural tourism. The company was dissolved on December 31, 2010.

Trade registry records of AGAPE Tourism, a company established in Turkey by Louven and two of his partners.

Louven says he was on good terms with local authorities, including the governor, and generally faced no trouble except during the early 2000s. At that time Turkey’s National Security Council (Milli Güvenlik Konseyi, MGK) classified missionary work as one of the country’s top threats. Following directives from the MGK, backed by powerful neo-nationalist generals, Turkish agencies were instructed to obstruct Christian groups’ activities, gather intelligence on them and run covert negative media campaigns.

Louven was also caught up in a massive state-run smear campaign against Christians in the country. Amid an artificially created and deliberately provoked anti-Christian frenzy, local media seized on a Christian pamphlet — likely distributed by Jehovah’s Witnesses — as evidence of missionary work and wrongly accused Louven of being behind it. Although Louven and his group had no connection to Jehovah’s Witnesses, police raided his office and began investigating the guest houses he operated for tourism purposes.

Yet Louven and his family survived that turbulent period. They continued to engage with locals, run their businesses and maintain their properties both in the city and the countryside.

But that changed on August 25, 2019, when the family visited the Muğla Provincial Directorate of Migration Management and were informed that their residence permits had been denied, forcing them to leave the country within 10 days.

“The only possible reason I can think of is our religious belief and the fact that we occasionally share it with local people,” Louven said in his petition posted on the Change.org campaign website.

“Freedom of belief and the right to express it is a fundamental human right, and Turkey is a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Yet, despite my retirement in Turkey, our home, our farm and our family’s legal and stable life here, we now face deportation,” Louven wrote.

Louven decided to challenge the migration agency’s decision, hoping his daughter could complete her final year of university. Meanwhile, his wife was denied re-entry to Turkey upon returning from a trip to Austria.

However, under pressure from the intelligence agency, the judicial system failed to address the injustice faced by the Louven family, with courts simply abiding by the government’s undeclared policy targeting non-Muslim minority groups.

On the surface the N82 code assigned to Louven does not constitute an outright entry ban to Turkey, as individuals with this code are required to obtain pre-approval before entering the country. However, in practice, it functions as a de facto entry ban, since all those who applied for pre-approval were rejected by Turkish consulates based on this code and the accompanying MIT reports.

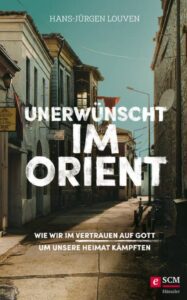

When the police eventually came after him, Louven was forced to flee in August 2020. In 2021, he authored a book titled “Unerwünscht im Orient: Wie wir im Vertrauen auf Gott um unsere Heimat kämpften” (Unwanted in the Orient: How We Fought for Our Home, Trusting in God), detailing his legal and spiritual journey during turbulent times in Turkey.

Louven’s case is by no means isolated. Nordic Monitor reported last year that many Christians in Turkey were wrongly labeled as spies and assigned codes marking them as national security threats. As a result, hundreds of foreigners flagged by MIT faced deportation, had their residence permits revoked or denied renewal, and, in some cases, were refused entry visas when attempting to return to Turkey after trips or holidays.