Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

The recent conviction of a former special operations officer on espionage charges in Turkey underscores Turkish intelligence agency MIT’s (Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı) assertive campaign to surveil and monitor the activities of foreign diplomats in the country, offering a rare glimpse into the agency’s operational capabilities.

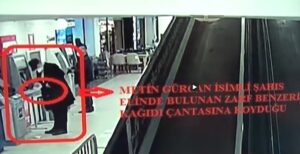

The evidence submitted to the court by MIT included both video footage and still photographs of Metin Gürcan — a former military officer with 16 years of service — meeting with Italian and Spanish diplomats, who were allegedly intelligence operatives. Gürcan was also documented receiving cash payments in exchange for services allegedly provided to foreign governments.

The criminal case, initiated in 2021 by a public prosecutor following years of surveillance by MIT, does not fully disclose how the agency obtained the alleged evidence against Gürcan. However, it offers significant insight into MIT’s modus operandi and the invasive surveillance tactics employed against foreign diplomats stationed in Turkey.

The agency sought to restrict the flow of information surrounding the case in an effort to conceal its activities and intelligence-gathering methods. In February 2022 the Ankara 26th High Criminal Court, where the trial was being held, issued a media gag order shortly after the public prosecutor filed the indictment. During the initial hearing, the court further ruled that all proceedings would be conducted behind closed doors, excluding both the public and the press.

Nevertheless, information obtained from the case file by Nordic Monitor offered valuable insight into the clandestine operations of MIT — an agency controlled for over a decade by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s closest confidants and increasingly instrumental in upholding his authoritarian regime.

The information suggests that the spy agency concluded Gürcan had been recruited as an informant by Spanish and Italian intelligence operatives, allegedly operating under diplomatic cover at their respective embassies since 2016. According to the findings, Gürcan provided information deemed sensitive to Turkey’s national security in exchange for cash payments that were never reported in his income tax statements.

This assessment followed the discovery that Gürcan maintained regular, in-person meetings and extensive online communications with the diplomats. He was photographed receiving cash payments in envelopes and even signing a receipt to acknowledge the transaction.

The still images extracted from the video footage suggest the agency employed concealed cameras positioned in close proximity to Gürcan during his interactions with foreign diplomats, underscoring the meticulous nature of the surveillance.

Some of the footage was also sourced from CCTV recordings at various venues, including restaurants and shopping malls, indicating that police obtained recordings from private property owners after MIT provided the information to the prosecutor, who then ordered the police to gather evidence.

The MIT intelligence report also detailed the content of conversations Gürcan held with foreign diplomats, suggesting that the agency had, in some instances, bugged meeting venues in advance. One such meeting reportedly occurred inside the car of an Italian diplomat for approximately 45 minutes in a secluded section of a parking lot, raising the possibility that MIT either rigged the diplomat’s vehicle with a listening device or employed advanced remote surveillance techniques to eavesdrop on the conversation.

The case file specifically references technical surveillance, a practice referred to in Turkish as “ortam dinlemesi,” which indicates that Turkish agents successfully intercepted entire conversations in designated environments using concealed microphones or listening devices. Verbatim excerpts from the Spanish diplomat’s conversation with Gürcan were included in the indictment.

The MIT report further revealed that Gürcan was assigned the codename “Gurmet” and was occasionally referred to as a “source” by the Spanish intelligence service, implying that Turkish intelligence intercepted not only Gürcan’s communications but also the confidential communications of the Spanish diplomats.

The Spanish diplomat classified the reliability of the information obtained from Gürcan as level “3” and its accuracy as level “C,” further indicating, according to the indictment, that MIT had penetrated secure communication channels of the Spanish Embassy. The indictment also alleges that when the Spanish diplomat’s posting ended on June 30, 2019, Gürcan’s original handler handed him over to a successor.

The MIT report does not explain how the agency breached the Spanish diplomat’s secure communication channels, but the language strongly implies that the intercepted information originated not from Gürcan, but directly from the Spanish diplomat’s end.

Overall, the surveillance, eavesdropping and interception of phone calls, emails and other communications involving Gürcan and his contacts enabled the Turkish agency to uncover the nature of the activities he had conducted on behalf of foreign governments.

The information provided by Gürcan encompassed Turkey’s operations in Syria, Iraq and African countries such as Libya; movements of military units; details of domestically developed UAVs; internal factionalism within the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK); and the deployment of Russian S-400 missile systems acquired by Turkey, as well as insights into President Erdogan’s health and the activities of various political parties.

In his conversations with foreign diplomats, Gürcan allegedly claimed to have obtained information from on-the-ground sources, which the prosecutor interpreted as data not publicly accessible. Throughout the trial, Gürcan and his defense team consistently maintained that the information he provided was derived solely from open sources while acknowledging that payments received were for services rendered.

The MIT report emphasized that given Gürcan’s background as a special operations military officer, he had received counterintelligence training and was therefore fully capable of assessing the sensitivity of the information in question. Nevertheless, he allegedly transmitted this sensitive information to foreign entities.

The report further alleged that Gürcan compiled classified data related to Turkey’s military, defense industry, foreign relations, irregular migration flows and economic policy — information that could potentially be exploited to develop strategies favoring third countries.

The report noted that Gürcan acquired information from individuals, institutions and organizations that were inaccessible to foreign intelligence operatives, effectively undermining the defense’s claim that the data originated solely from open sources.

Gürcan’s role as a founding member of the small opposition party Demokrasi ve Atılım (DEVA), chaired by Ali Babacan, a former ally of President Erdogan who previously served as deputy prime minister, foreign minister and economy minister in Erdogan’s cabinets, afforded him access to political circles and people possessing extensive knowledge of the Turkish government’s clandestine operations due to their former high-level positions.

Government pundits have now begun questioning who introduced Gürcan to Babacan and how he became one of the founding members of DEVA, suggesting that the espionage case may need to be expanded to include party officials who could have been complicit in facilitating Gürcan’s activities.

When Gürcan was detained by police in Istanbul on November 26, 2021, and formally arrested three days later during his arraignment at the Ankara 6th Criminal Court of Peace on charges of “obtaining information that must remain secret for political or military purposes,” Babacan voiced his disapproval of footage showing Gürcan receiving cash from foreign diplomats. Babacan acknowledged that the images posed an ethical dilemma for the party while also suggesting that the government might be using the case as a pretext to crack down on the opposition.

However, as the case progressed, Babacan and his party quickly distanced themselves from Gürcan, who was reportedly compelled to sever all ties with the party, including relinquishing his membership. Following his conviction on May 23, 2025, and sentencing to almost 17 years in prison, the party officially declared on June 2 that it had no association with him. It appears Babacan concluded that the optics were damaging for the party, effectively throwing Gürcan under the bus.

In his defense Gürcan consistently maintained that he never shared any classified information with diplomats, asserting that all the data he provided originated from open sources, and denied acting against Turkey’s interests.

In his indictment the public prosecutor challenged Gürcan’s defense, arguing that Spain and Italy — equipped with extensive resources and experts — had no need for information sourced from open channels. The prosecutor said foreign intelligence services regularly paid the suspect cash sums of $400, €500 or £330 for information unavailable to the public. Notably, the payment rose to $1,000 for a report Gürcan prepared on Turkey’s UAV programs.

“‘It has been determined that the suspect participated in numerous training sessions and operations involving military secrets and that he had access to the state’s military and political secrets,’ the indictment stated. The prosecutor emphasized that the information Gürcan obtained in exchange for money — classified as political and military secrets — could not have been sourced from open materials.

“A preliminary examination of digital materials revealed that he consistently used the term ‘my sources,’ and the content of the information indicates that these sources refer to public officials or individuals in critical commercial or political positions,” the indictment stated.

In one of the intercepted messages, Gürcan said, “I had my meetings, there are very good insider insights,” which the prosecutor interpreted as an acknowledgment of obtaining information from private sources rather than open channels.

The prosecutor further asserted that a report prepared by Gürcan for foreign diplomats, titled “Update on the Defense Industry & Geopolitical Issues,” contained information unavailable from open sources, with sensitive data allegedly sourced from an individual employed by the Presidency of the Defense Industry (SSB), Turkey’s premier defense procurement agency.

According to the indictment, which incorporates assessments from the SSB and the Ministry of Defense, the information contained in the report is of critical importance to national security and defense. It states that the document obtained by Gürcan was prepared with extensive detail on defense industry programs and projects deemed vital to Turkey’s national security.

The report was said to contain information about President Erdogan’s requests from the SSB as well as details regarding classified correspondence and data exchanges between the Air Force Command, the SSB and other institutions. It was assessed that the entire report in question qualified as a state secret.

Maps extracted from Gürcan’s phone, which detailed Turkish military bases, were assessed by the Ministry of Defense as potentially sourced from publicly available mapping programs. However, the handwritten English annotations on the maps — referring to specific military units such as the “Turkish Military 20th Armored Brigade,” the “70th Mechanized Infantry Brigade,” the “155 mm Storm Howitzer Battalion,” the “Gendarmerie Special Operation Battalion” and the “Commando Battalion Offensive Forces Border Security Brigade (Not well-trained, thus Defensive Forces)” — were deemed “information that, by its nature, must remain confidential for the security of the state and its domestic and foreign political interests.”

In his defense, Gürcan cited the COVID-19 pandemic as justification for holding a secret meeting with a foreign diplomat inside the diplomat’s car in a shopping mall parking lot. However, the prosecutor dismissed this argument, asserting that spending 45 minutes in a confined space during the pandemic was illogical and contravened the public health regulations in force at the time.

On June 15, 2023, the Ankara 26th High Criminal Court convicted Gürcan on charges of “obtaining information that, by its nature, must remain confidential for the security of the state and political interests,” while dropping other charges and sentencing him to five years in prison. However, the 4th Chamber of the Ankara Regional Appeals Court subsequently overturned the verdict and ordered a retrial before the same court

The case was finally concluded on May 23, 2025, with Gürcan convicted under Article 328 of the Turkish Penal Code for “repeatedly obtaining information that must remain secret for the purpose of political or military espionage.” On the same day, he was transferred to the Sincan Type L No. 2 Closed Prison.

Gürcan served in the military from 1998 to 2014, including overseas deployments as a special forces operative in countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. After retiring from the military, he pursued a career as a security analyst, contributing to publications such as Al-Monitor’s Turkey Pulse and for The Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP). His imprisonment abruptly interrupted this post-military professional path.

This is not the first time that MIT’s surveillance of foreign diplomats in Turkey has been exposed. The intensification of intrusive intelligence gathering specifically targeting Western embassies — and the close monitoring of US and European diplomats in Ankara — was publicly confirmed by Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu on May 11, 2022.

Speaking to a group of supporters in Aydın province, Soylu cited excerpts from the transcript of a closed-door meeting at a Western embassy. He did not say how he had obtained the information on the content of the talks held at the embassy. It is likely that the intelligence agency hacked the phone of one of the attendees or had an asset or informant in the embassy.

Although Soylu did not name the country, the pro-government media claimed the meeting was held at the German Embassy in Ankara and attended by a senior figure from the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP).

“I will cite each and every sentence you [opposition lawmakers who attended the meeting at the embassy] uttered. You shamelessly talked to the ambassador of a European country about how many seats you will win in [the] 2023 [election]. Let me give you another tidbit. You talked about Çağatay Kılıç”, Soylu said about the meeting. Kılıç was at the time the head of the Turkish Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee and currently serves as the national security advisor to Erdogan.

“You talked about the fact that the first president [from the opposition alliance] to be elected [in the next election] will serve for two or three years, and then you will have to choose a new president. You evaluated how the Ukraine-Russia crisis and the results of that war would affect Turkey. You talked about all the details within the [opposition] Peoples’ Alliance [bloc], about [opposition political leaders] Ali Babacan and Ahmet Davutoğlu and how to get votes from the HDP [pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party].”

Turkish intelligence has become a key instrument for the Erdogan government’s consolidating and maintaining its grip on power. Under a presidential mandate, MIT has been tasked with orchestrating false-flag operations, conducting influence campaigns, creating and managing radical proxy groups, initiating politically motivated criminal cases and conducting espionage abroad — particularly targeting critics and investigative journalists. Over the past decade, the Erdogan administration has enacted several intelligence laws granting the agency broad immunity from criminal and administrative investigations, effectively providing MIT with carte blanche and total impunity.