Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

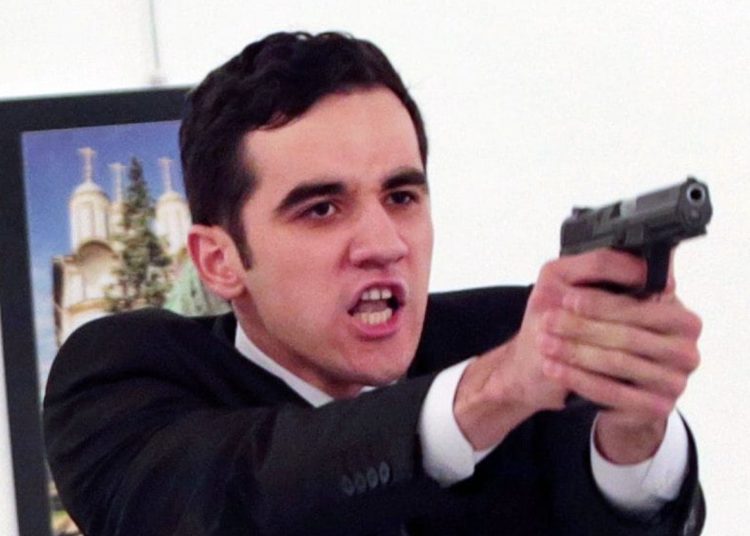

Turkish authorities ignored troubling signs in a psychological assessment of the police officer who gunned down Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov in 2016 and ignored red flags indicating a tendency to violence.

According to the confidential personnel file at the Security General Directorate (Emniyet), a copy of which was obtained by Nordic Monitor, 22-year-old Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş, a radicalized police officer, went through a psychological assessment test before he was accepted for a job with the riot police in 2014.

According to the routine screening process for all new employees in the force, Altıntaş also underwent a psych evaluation test in Ankara. The test results show that psychologist Nurcan Gezginci made an error in tallying the total score based on the individual responses he gave to various questions.

On August 18, 2014 the assassin took the Symptoms Checklist-90 (SCL-90), a test used by mental health professionals to assess psychological symptoms. It has 90 questions, and the respondent indicates his answer by choosing a number from 0 to 4, indicating “not at all,” “a little bit,” “moderately,” “quite a bit” and “extremely.”

A review of the results of the questions he answered shows there were some indications that he was troubled and as such might not be fit to serve as a police officer. When he was asked if he felt most people can’t be trusted, he chose number 3, meaning he felt that way quite a bit.

The Symptoms Checklist-90 (SCL-90) questionnaire as answered by the killer of the Russian ambassador:

The alarm bells must have sounded when he was asked about “having urges to beat, injure or harm someone.” Altıntaş answered 3, one notch down from having extreme feelings about it. Yet Turkish authorities simply decided to ignore such a strong indication that he would most likely harm someone as a police officer who was provided a government-issued service weapon.

A similar indication was also spotted in the questionnaire when he was asked whether he had “urges to break or smash things.” He responded again with a three. He also admitted that he was moderately bothered by “unwanted thoughts, words, or ideas that won’t leave his mind.”

The questionnaire showed that the assassin only answered 89 questions, skipping the last one, which asked how much he was bothered by “the idea that something is wrong with your mind.” Yet the psychologist treated his responses as if they were complete and made her calculations of his test scores accordingly.

An expert report dated March 9, 2018 analyzed the assassin’s 2014 test scores and was submitted to the prosecutor’s office, confirming the problems in recruiting such a person. The report concluded that Altıntaş had feelings of paranoia and noted that his psychological profile would be indicative of a seriously psychopathological personality if the initial examiner hadn’t made an error in the tally by treating the results as if he had responded to all the questions.

The report further underlined that the paranoid Altıntaş might have tried to project a better image of himself, hiding his true feelings because of the defensive nature often associated with paranoid people. It suggested that the real score must be revised with an additional point, meaning Altıntaş’s psychological profile would be worse than it already was.

What is more, Altıntaş’s personnel file indicated no further review of his psychological profile after this initial screening, which clearly spelled trouble. His medical records show no treatment for any psychological disorder in the two years he served as a police officer.

The Police Academy has a special psychology unit at the Rüştü Ünsal Police College where the assassin was trained; yet the school records did not show any referral to the psych ward by the school administrators. The medical file maintained at the Security General Directorate after he started working as a police officer also did not show any psychological counseling for Altıntaş. It wasn’t until 2020 that the Turkish government required an annual mental health screening for all police officers and hired more counselors following a spike in suicides in the force.

The result of the psychological test was incorrectly tallied and analyzed by police psychologist Nurcan Gezginci:

Altıntaş’s employment as a police officer by the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan came after a mass purge of police officers and the sacking of senior police chiefs including police academy administrators in the aftermath of major corruption scandals in 2013. Erdoğan blamed the revelation of his corrupt business dealings as well his secret meetings with one-time UN-sanctioned al-Qaeda financier Yasin al-Qadi on the Gülen movement.

Erdoğan started purging many veteran police chiefs whom he claimed to have been affiliated with the movement. Empty slots in the police force were often filled with religious and nationalist zealots who subscribed to the Erdoğan government’s political Islamist ideology.

The cell phone records, bank wires and computer logs obtained for the Altıntaş as well as witness statements all pointed to several radical clerics who either worked for the Turkish government’s religious authority, the Diyanet, or were long supported by the office of President Erdoğan.

There are a number of pieces of evidence in the case file that show the killer was in fact radicalized by jihadist literature, attended prayer circles organized by pro-government jihadist cleric Nurettin Yıldız and had been befriended by known al-Qaeda militants. However, the government did not pursue the leads into jihadist networks and did not investigate the al-Qaeda figures who had worked with the killer. It was also revealed that the Erdoğan government rewarded the killer with 34 bonuses in two years’ time.

The prosecutor’s indictment concerning the murder of Russian envoy shows the incorrect analysis of the psych profile questionnaire completed by the assassin. A subsequent report lays bare the mistakes made by Turkish officials in hiring him:

His psychological profile showed he was a perfect candidate for quick radicalization given the right circumstances, guidance and nurturing. According to multiple statements by his colleagues and friends, he was a withdrawn, reclusive, antisocial man who kept to himself. He had sex with a prostitute but wanted to repent and cleanse himself of what he considered his sins. He wanted to create a big bang to leave his mark on this world and be rewarded in the afterlife.

Altıntaş wanted to quit his job and go to Syria to fight alongside jihadists, tried to learn Arabic in his free time, attended study circles set up by radical groups and financially supported jihadist NGOs, some of which had already been reported to the UN Security Council by Russia as entities that were helping al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). He purchased and read dozens of al-Qaeda and ISIS jihadist books that are freely available for sale in Turkey, where the government ironically shut down nearly 200 media outlets and imprisoned 164 critical and independent journalists.

The prosecutor’s claims that the assassin was linked to the Gülen group collapsed when the trial concerning the murder of the Russian envoy started and key defendants recanted their earlier statements extracted under duress and submitted medical reports to prove they had endured torture and ill-treatment until they agreed to sign false statements. Many government witnesses did not show up for cross-examination despite repeated motions from the defense lawyers and defendants. Those who appeared in court provided conflicting statements, while some recanted earlier statements they had given to the police.

Turkish authorities turned down several Russian government requests such as running a lie detector test on a key suspect whom Turkey claimed to be complicit in the assassination of the Russian ambassador. The rejection by Turkey came despite the fact that the suspect, Mustafa Timur Özkan, who repeatedly said he had nothing to do with the murder, volunteered to undergo the Russian government lie detector test, eager to prove his innocence.

Özkan was the organizer of the art exhibition at which the Russian envoy was assassinated Altıntaş on December 19, 2016. He said he planned the exhibition in close coordination with the Russian Embassy and denied the prosecutor’s claims that the exhibit was ordered by the Gülen movement to set the stage for the murder.

Turkey also rejected the Russian government’s urgent request not to conduct an autopsy on the body of slain ambassador.

The trial concluded in March 2021 with the conviction of scapegoats. The real culprits who helped the assassin radicalize remain free with the help of the Turkish government. The Russian government’s own investigations is still pending.