Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

As part of a global campaign to intimidate critical journalists who live in exile, the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan filed an extradition request with Germany seeking the return of a Turkish journalist on fabricated charges.

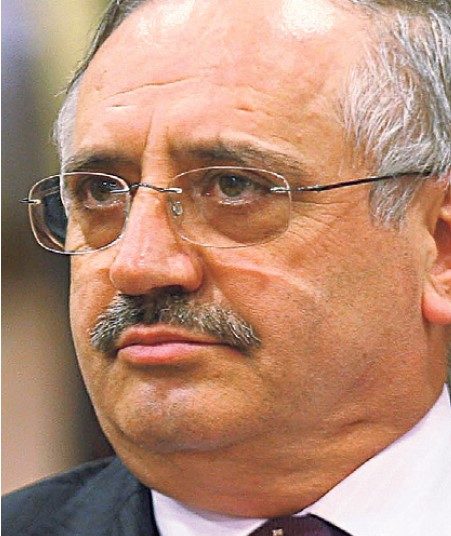

According to Turkish government documents obtained by Nordic Monitor, Halit Esendir, a former editor for Turkey’s one-time most highly circulated Zaman daily, faced an extradition request filed by Turkey with the German government.

Esendir was president of the Media Ethics Council (MEK), an Istanbul-based advocacy group for professionalism in the media that was unlawfully shut down by the government in 2016. His advocacy on press freedom and freedom of expression in Turkey and critical views of the Erdoğan government have apparently bothered Turkish authorities, who sought his forcible return from Germany.

It’s unclear what happened with the request, which was initiated in 2017, as the communication between the courts and the Justice Ministry did not show the response from the German government. In similar cases, Germany refused to turn over critics to Turkey, citing violations of the European Convention on Human Rights.

He is also affiliated with the Gülen movement, a civic group that is critical of the Erdoğan regime and that has been the subject of a brutal crackdown in Turkey. More than half a million people who were alleged to be Gülenists have faced punitive legal action, primarily in the form of detentions and arrests, in the last six years.

Turkish court’s ruling that shows Turkey sought the extradition of a critical journalist from Germany:

Turkish authorities seek two aggravated life sentences in addition to some 50 years in prison for 66-year-old Esendir on nine charges. Aggravated life, which replaced the death penalty in 2004, is the harshest sentence under Turkish criminal law. It imposes severe restrictions on inmates, solitary confinement and no early parole, which violates the European Convention on Human Rights, to which Turkey is a party. The Erdoğan government often sentences its critics to aggravated life in order to maintain its intimidation campaign against opponents, critics and dissidents.

The journalist’s appearances as a commentator on Turkish TV during which he criticized the Erdoğan government’s policies were cited as criminal evidence against him, according to review of documents in his case file. He is the subject of six outstanding arrest warrants on a range of criminal charges, from defamation of the president to false accusations of terrorism.

Esendir had been an outspoken critic of press freedom restrictions when the Erdoğan government introduced a range of measures to limit access to public and government venues by journalists who work for critical media outlets in 2014.

When Erdoğan called CNN reporter Ivan Watson a “flunky” and an “agent” over CNN International’s coverage of anti-Erdoğan government protests in the summer of 2013, Esendir was one of those who denounced Erdoğan’s remarks. “Ivan Watson is a journalist who has a press card issued by the Office of the Prime Minister of Turkey. Labeling an accredited journalist as an agent is unacceptable,” he said. Esendir underlined that there was no merit to Erdogan’s accusations, labelling his remarks as slander.

He rebuked the Erdoğan government when the independent Taraf daily faced a politically motivated fine by the tax authority as part of an attempt to silence critical media outlets in June 2014. Esendir described the fine on Taraf as an intimidation tactic directed at the Turkish press. “We haven’t seen such practices for a long time in Turkey. I hope the government changes course and that Turkey returns to normalcy,” he said.

Taraf was shut down by the Erdoğan government in 2016, and most of its editors and journalists were imprisoned, including former editor-in-chief Ahmet Altan and investigative reporter Memet Baransu.

He had harshly criticized the seizure of some media outlets owned by the İpek Media Group in October 2015, warning that the seizure was a virtual attempt to overturn the constitutional order. Turkey’s third-largest media outlet, managed by Koza İpek Holding, which was also the owner of national television networks Kanaltürk and Bugün TV, the Millet daily, a radio station and the English-language news website BGNNews.com, were all taken over by the government in 2015 and turned into mouthpieces for government propaganda. They were closed a year later.

Esendir was also in the forefront when the Erdoğan government decided to exclude a number of journalists and media organizations from covering the 2015 G-20 summit in Turkey. “The accreditation shame, which means restriction of freedom of expression at a meeting attended by the most developed nations of the world, does not befit our country,” he said. He called on the authorities to allow all journalists and media outlets to cover the event.

Warrants issued for critical journalist who lives in exile:

In November 2015 Esendir criticized the government for arresting Cumhuriyet’s then-editor-in-chief Can Dündar and Erdem Gül, the paper’s Ankara representative, saying the arrests clearly showed that media freedom no longer exists in Turkey.

In his statement Esendir said unlawful practices were being carried out against journalists brazenly and openly in the country. Supporting Dündar and Gül, Esendir said both his colleagues were just engaging in journalism. “What is being tried is actually the profession of journalism and people’s right to information. People have the right to learn the facts from journalists. In countries where journalists are arrested for doing their jobs, the existence of a democratic state of law is out of the question,” Esendir said.

President Erdoğan personally sued Dündar and requested that he be given a life sentence, an aggravated life sentence and an additional 42 years in prison on charges related to a variety of crimes ranging from espionage to attempting to topple the government and exposing secret information. Dündar moved to Germany to escape wrongful imprisonment.

The government came after Esendir in December 2015 with a detention warrant issued for him. He said he was being punished because the council he led had defended freedom of the press and continually reported violations. He had to flee Turkey to escape prison on bogus charges.

Journalist’s TV commentary was cited as criminal evidence against him:

Most of the charges the Erdoğan government levels against critics are based on anti-terror laws, including defamation and coup charges that are often abused by the criminal justice system to punish opponents, critics and dissidents who have done nothing more than express opposing views.

The Erdoğan government added coup charges against Esendir in the aftermath of a false flag coup attempt in July 2016 although there was no evidence in the case file suggesting that he had somehow been connected to the putschist attempt, which was believed by many to have been a plot orchestrated by the Turkish president himself to set up the opposition for mass persecution and a purge of nearly 150,000 people from government jobs.

Turkish authorities also sought an INTERPOL Red Notice for Esendir. Almost all European countries at one time or another have balked at Turkey’s politically motivated extradition requests for Gülenists, and INTERPOL repeatedly warned the Erdoğan government against abusing law enforcement cooperation mechanisms that were designed to combat real criminals after Turkey attempted to flood the INTERPOL system with fraudulent filings.

The INTERPOL Red Notice request prepared by the Turkish government: