Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

A Turkish al-Qaeda–linked cleric who relocated to Syria’s Idlib province to advance jihadist activities has been operating under the protection of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı, MIT), despite an outstanding arrest warrant for him in Turkey, Nordic Monitor has learned.

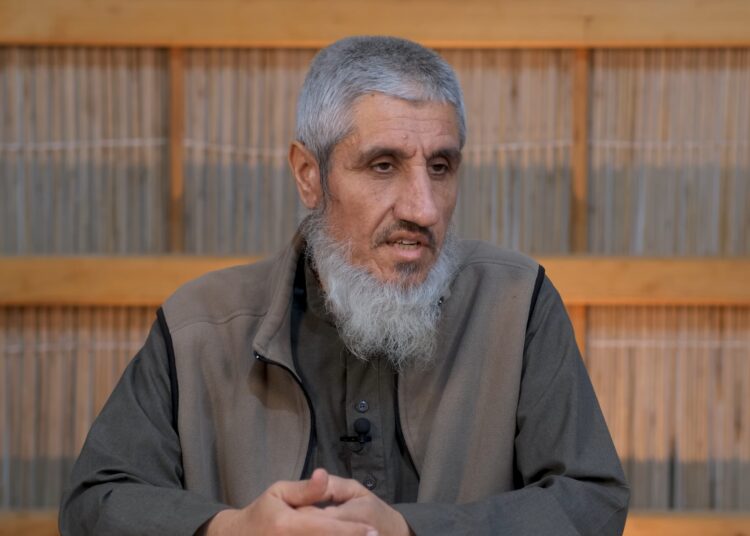

Musa Abu Jafar (also known as Ebu Cafer or Ebu Sumeyye, whose real name is Musa Olgaç) is a Salafist cleric who has long promoted jihadist causes across multiple countries, from Pakistan to Egypt, before ultimately settling in Idlib to continue his activities.

A terrorism investigation launched into him in 2011 on allegations of al-Qaeda membership was quietly shelved in 2014 by the Islamist government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, after senior police chiefs and prosecutors involved in the case were removed from their posts.

According to information obtained by Nordic Monitor, Abu Jafar moved to Syria at the request of MIT, established a base in Idlib province, an area under heavy Turkish military and intelligence control, and expanded his network of followers. His primary audience has consisted of Turkish nationals who traveled to Syria to join jihadist groups as well as sympathizers seeking to establish a sharia-based state in Turkey.

Although Abu Jafar regularly posts videos on YouTube and shares ideological messages on X to reach a wider audience, many of his followers travel directly from Turkey to Idlib to meet him in person, receive guidance and attend his sermons. While an arrest warrant remains formally in place, it has never been enforced, serving only as a cosmetic gesture to suggest that the Erdogan government is cracking down on jihadist terrorism.

Turkey could easily apprehend Abu Jafar in Idlib, where Turkish police, military and intelligence services maintain a significant presence. Yet he has remained untouched for years, shielded by Turkish intelligence, which has relied on jihadist operatives abroad to advance the political objectives of the Islamist Erdogan government both domestically and across the region.

From his base in Syria Abu Jafar has built multiple networks inside Turkey under various names, often disguised as religious education initiatives or charitable activities. While some of these structures have occasionally come under police scrutiny, particularly following deadly attacks carried out by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), they have largely survived. Most detained jihadists have been released by prosecutors or courts that have frequently treated Islamist radicals with leniency.

A recent investigation into what authorities described as an ISIS cell revealed that Abu Jafar had even established a foothold in Turkey’s western province of Muğla, a largely secular region and one of the country’s major tourist destinations for Turks and foreigners.

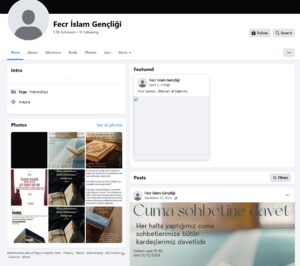

For nearly a decade, the network in Muğla operated under the name Fecr İslam Gençliği (Islamic Dawn Youth Movement), led by two brothers, Şafii İzgi (42) and Onur İzgi (30), both followers of Abu Jafar. The group ran a religious madrasa in Muğla’s Şeyh neighborhood while authorities turned a blind eye to the network’s radical activities.

The brothers first traveled to Syria in 2015, spending time in territory controlled by the Turkey-backed Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), formerly affiliated with al-Qaeda. They traveled to Syria again in 2021 and 2025.

Police operations conducted in October 2025 and January 2026 resulted in the detention of 13 suspects, including the two brothers. Financial records, surveillance data and wiretaps showed that the group had actively assisted jihadists, including individuals with links to ISIS.

In his police interrogation, Onur İzgi admitted that during his most recent visit to Idlib in February–March 2025, where he stayed for 37 days, he met Abu Jafar and spent time with him. His brother Şafii later joined them in Idlib. Onur told investigators that around 50 Turkish nationals, many with al-Qaeda backgrounds or affiliations, regularly attended Abu Jafar’s weekly sermons.

Both brothers are listed as volunteers with the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (İnsan Hak ve Hürriyetleri ve İnsani Yardım Vakfı, IHH), an al-Qaeda–linked Turkish charity, as well as with AFAD (Afet ve Acil Durum Yönetimi Başkanlığı), Turkey’s government-run Disaster and Emergency Management Authority. Records show that they received training in handling hazardous materials, including explosives.

Unde the pretext of humanitarian assistance, both IHH and AFAD had transferred funds, arms and logistical supplies to jihadists in Syria during the Syrian conflict.

Şafii İzgi also traveled to Afghanistan to establish jihadist connections in line with Abu Jafar’s vision of global jihad.

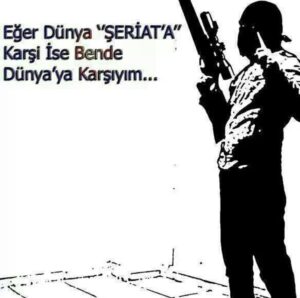

Evidence seized from the group’s madrasa included handwritten notes by Şafii İzgi that shed light on the organization’s long-term objectives.

“When we are conducting outreach [da‘wah] in Muğla, the essential thing is that we must not lose our sense of vigilance. The main objective will be preparation for jihad,” he wrote. The note suggests that the group’s ambitions extend beyond establishing a sharia state abroad and include Turkey itself. Their ostensibly non-violent activities appear to serve as a precursor to an eventual armed campaign.

In another handwritten document Şafii discussed indoctrinating young children in jihadist ideology, urging followers to establish a youth camp under strict security protocols and encouraging them to study the history of global jihad. During questioning, Şafii admitted that he had authored the notes.

The Muğla cell highlights the depth and reach of Abu Jafar’s network inside Turkey, extending beyond conservative strongholds into western regions traditionally opposed to Islamist politics. The Erdogan government, in effect, enabled this extensive jihadist network by shielding Abu Jafar from prosecution, facilitating his escape and helping him establish a new base in Idlib.

The shuttered 2011 investigation in Turkey revealed that Abu Jafar had assisted numerous individuals in joining armed jihadist groups in Syria, including al-Qaeda and ISIS. He also helped establish a jihadist cell in Egypt, sending Turkish militants there on the pretense of studying Arabic and Islamic theology. A safe house he managed in Cairo was raided by Egyptian authorities in 2007, leading to his detention for three-and-a-half months before he was extradited to Turkey.

On February 18, 2011, Abu Jafar fled to Pakistan, narrowly escaping a police operation two months later in which 42 al-Qaeda suspects were detained, on April 12, 2011. As the investigation expanded, he remained a wanted fugitive, with law enforcement closing in on his inner circle and monitoring his communications with family members in Turkey.

However, in January 2014, prosecutors and police chiefs were blocked by the Erdogan government from advancing the case. By March 2014 all al-Qaeda-related investigations and surveillance programs had been halted. The government did not want the flow of Turkish and foreign fighters disrupted. MIT, then headed by Islamist figure Hakan Fidan, sought a free hand to facilitate the movement of jihadists and the supply of arms and logistics as part of Turkey’s effort to overthrow Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Turkey’s criminal justice system has since systematically failed to dismantle jihadist networks, reflecting the Islamist policies of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) under President Erdogan, who has repeatedly displayed ideological sympathy toward jihadist actors.

The recent crackdown on Fecr İslam Gençliği, a local affiliate of Abu Jafar’s network, is therefore unlikely to produce meaningful results. Most suspects are expected to be released, with charges either dropped or resulting in lenient sentences, outcomes that fall far short of deterring the continued spread of jihadist extremism in Turkey and beyond.