Levent Kenez/Stockholm

US President Donald Trump’s decision to impose a 25 percent tariff on countries trading with Iran, following a renewed crackdown by Iranian authorities on anti-government protests, threatens to put Turkey’s economy and energy strategy under renewed strain, even as relations between Washington and Ankara have recently entered a period of normalization and closer coordination.

Trump announced that countries continuing commercial ties with Iran will face an additional 25 percent customs tariff on their trade with the United States, a measure that he said takes effect immediately. The White House offered no details on enforcement mechanisms, sectoral exemptions or country-specific waivers, leaving exporters, importers and governments scrambling to assess the fallout. The announcement marked a significant escalation from traditional sanctions enforcement, as it makes the mere act of trading with Iran sufficient grounds for punitive tariffs, regardless of whether sanctions are formally violated.

For Turkey, which maintains deep economic ties with Iran and relies on it for critical energy supplies, the implications are potentially severe.

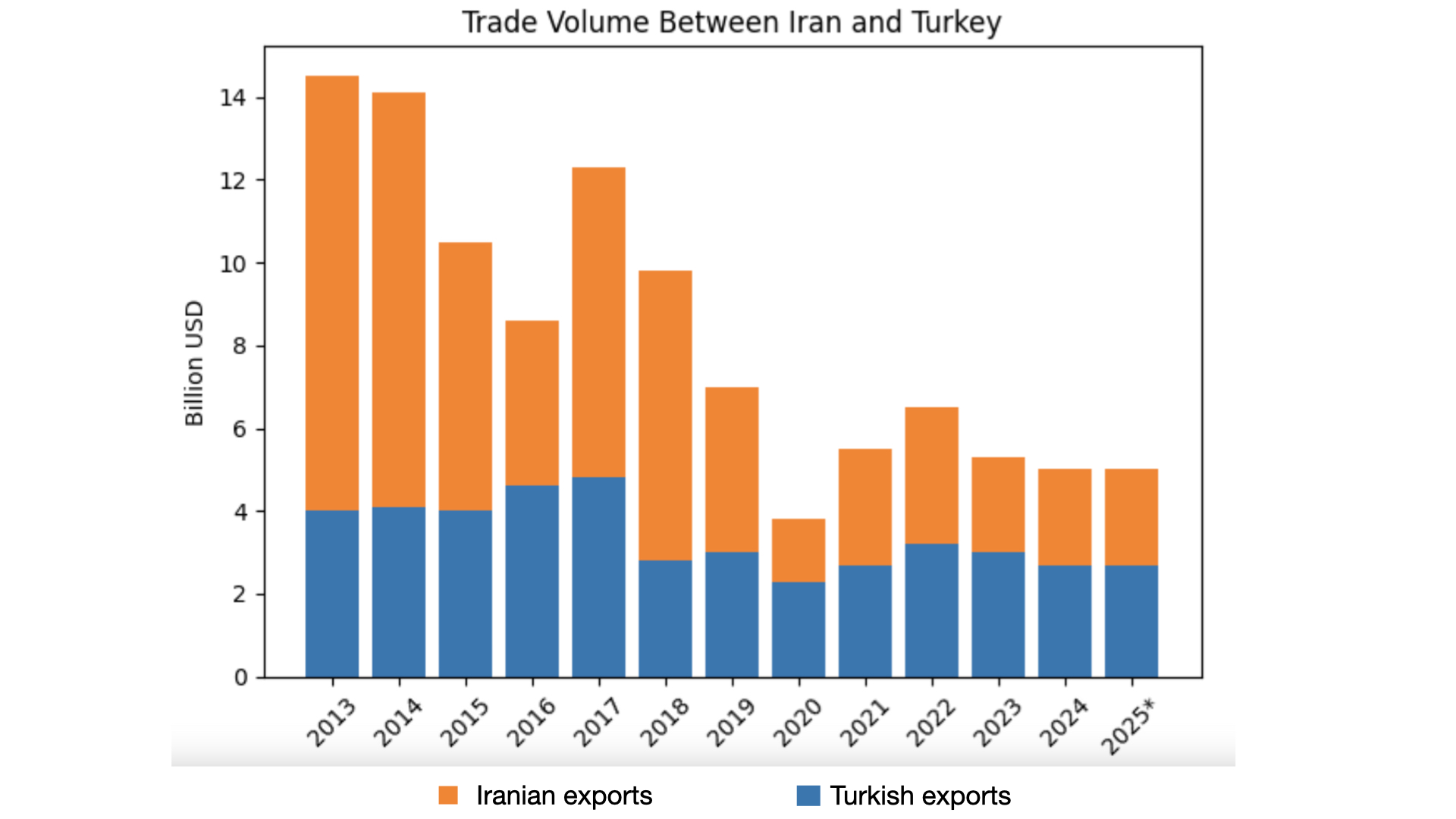

According to World Bank data, Iran’s exports to Turkey reached $5.8 billion in 2022, while Turkey’s exports to Iran totaled $6.1 billion the same year. More recent figures from Turkey’s TurkStat statistical agency show that in the first 11 months of 2025, Turkey exported $2.7 billion worth of goods to Iran and imported $2.3 billion, showing the resilience of bilateral trade despite years of US sanctions pressure. In energy alone, Turkey sourced 13.5 percent of its natural gas imports from Iran in 2024, a dependence that Ankara has struggled to reduce.

At the same time, Turkey’s trade relationship with the United States is economically significant. Bilateral trade volume fluctuated around $30 billion annually in recent years with Turkey exporting automobiles, machinery, textiles and steel products to the US, while importing aircraft, defense equipment, energy products and high-value industrial goods. A blanket 25 percent tariff applied to this trade would threaten Turkish exporters already strained by inflation, currency volatility and weak global demand.

What makes Trump’s move particularly disruptive is that it goes beyond traditional sanctions logic. Under earlier US regimes, penalties were generally tied to specific prohibited transactions, sanctioned entities or deliberate circumvention. Under the new framework, continued trade with Iran alone appears sufficient to trigger penalties, even if conducted openly, legally under Turkish law and outside US financial systems.

A guidance document prepared by Turkey’s Trade Ministry indicates that using money changers in trade with Iran is allowed, but cautions that the Americans may object:

Turkey’s experience navigating sanctions pressure is extensive and controversial. A guidance document prepared by Turkey’s Trade Ministry and circulated among exporters illustrates how Ankara has historically approached the gray areas of Iran trade. The document, framed as a “frequently asked questions” guide on US sanctions, details which sectors are targeted, how US authorities monitor transactions and what Turkish companies should consider when assessing risk.

One section of that guidance addresses a question many exporters quietly ask: whether proceeds from exports to Iran received through money changers or the hawala system can be booked without difficulty in Turkey. The answer is unequivocal: There is no obligation under Turkish law to repatriate export revenue from Iran, and such proceeds can be recorded without accounting problems. Hawala is an informal value transfer system widely used in the region, particularly in Iran-related trade, where funds are settled through trusted intermediaries rather than through the formal banking system. In practice, exporters receive payment in Turkey via local money changers or intermediary counterparties, while the corresponding settlement takes place separately between brokers. The document adds that a significant portion of Iran-related trade already flows through this system and that it is widely used in the region.

While the guidance includes warnings that US authorities strongly discourage such practices and may impose sanctions, the practical effect is to map out how trade has continued under pressure. It also reflects Ankara’s longstanding position that domestic legal compliance and US sanctions exposure are separate issues.

A second official document reinforces that point. Under a Turkish export regulation granting exemptions from mandatory repatriation of export proceeds, revenues earned from exports to Iran are not required to be brought back into Turkey through the banking system. The measure, designed to accommodate trade with sanctioned markets, further insulates Iran-related commerce from formal financial scrutiny.

In the past these arrangements allowed Turkey to maintain trade with Iran while managing, though not eliminating, US risk. Trump’s new tariff policy changes that calculus entirely. Even transactions conducted transparently, without concealment and without touching US financial channels, could now expose Turkey’s broader trade with the United States to punitive duties.

Turkey allows export revenues from Iran to bypass the banking system under an export regulation exempting mandatory repatriation:

The move inevitably revives memories of the Halkbank case, the most dramatic example of Turkey’s collision with US sanctions enforcement. US prosecutors allege that Turkey’s state-owned Halkbank orchestrated a multi-billion dollar scheme between 2011 and 2016 to help Iran evade sanctions by converting oil and gas revenues into gold and cash, disguising the transfers as humanitarian trade. The operation relied on front companies, falsified documents and political protection at the highest levels of the Turkish government.

The scheme came to light during a corruption investigation in Turkey in 2013, which implicated cabinet ministers and businessmen close to then–prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The investigation was shut down, prosecutors were removed and the charges were dismissed. One central figure, Iranian-Turkish trader Reza Zarrab, was later arrested in the United States, reached a plea deal and testified in federal court, detailing how the network operated and how bribes were paid to Turkish officials including the now-President Erdogan.

In 2018 a US jury convicted Halkbank executive Mehmet Hakan Atilla. In 2019 the US Department of Justice indicted Halkbank itself, charging the bank with fraud, money laundering and sanctions violations. After years of litigation, the US Supreme Court in October 2025 declined to hear Halkbank’s final appeal, clearing the way for prosecution. The case remains one of the most serious legal threats facing a Turkish state institution in US courts.

Meanwhile, Trump on Tuesday also indicated that Washington is closely following developments inside Iran. He urged Iranians to continue protesting and said that “help is on its way,” while announcing that he had suspended all contacts with Iranian officials amid an expanding security crackdown. US officials have not detailed what such support would involve, but the comments add to uncertainty over Iran’s political direction. Any significant political shift, including a possible change in the country’s leadership, would have direct implications for Iran’s relations with neighboring Turkey, where trade, energy cooperation and regional diplomacy have long been shaped by Tehran’s internal stability and its stance toward the West. How Iran emerges from the current unrest could determine whether bilateral commerce continues under restrictions, contracts further or moves onto an entirely new footing.