Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

As millions of Turkish flock to Turkey’s resort towns and cities for the summer holidays, the country’s intelligence agency, Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı (MIT), has ramped up covert operations aimed at recruiting informants from among the diaspora, Nordic Monitor has learned.

According to multiple sources familiar with MIT’s tactics, the agency — bolstered by sweeping powers under the increasingly authoritarian regime of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan — has intensified efforts to identify and recruit individuals with foreign residence or dual citizenship. These efforts are particularly active during the summer, when large numbers of expatriates travel to Turkey.

MIT agents stationed at Turkish embassies and consulates reportedly pre-screen individuals for potential recruitment. Upon arrival in Turkey, these targets are approached by agents — sometimes at airports — who attempt to persuade or pressure them into cooperating with the agency.

One expatriate who spoke to Nordic Monitor on condition of anonymity described a recent encounter with MIT officers at Istanbul Airport. A dual citizen long settled in Western Europe, the person was intercepted by a man and a woman who identified themselves as MIT agents. He was invited for a brief sit-down conversation and asked to provide information on specific individuals living in his adopted country.

“They told me they knew everything about me — my family, my profession, even my political views,” the expat recounted. “They insisted they weren’t interested in me personally, but rather the people I might know due to my line of work.” The person declined the request but expressed concern over the potential consequences of refusing, including arbitrary detention on fabricated charges during future visits to Turkey.

Similar accounts from other sources confirm that MIT has followed a systematic approach over the past decade, allowing it to establish an extensive network of assets and informants — particularly in Europe, where the largest number of Turkish expatriates resides. The agency’s primary objectives include monitoring political dissidents, influencing the foreign policy of host nations through proxies, identifying possible vulnerabilities and enhancing Turkey’s diplomatic leverage.

To manage these operations, MIT has established special units based at major airports in Istanbul and Antalya — two of Turkey’s busiest travel hubs. While MIT maintains a permanent presence at most airports, these specialized teams are tasked exclusively with recruitment operations and report directly to headquarters in Ankara.

Although MIT also deploys operatives abroad under official cover — such as staff from the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), the Maarif Foundation, state-news agency Anadolu, the Yunus Emre Institute or the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) — recruiting from the diaspora offers unique advantages. Expatriates are typically well-integrated into their host countries, fluent in the local language and familiar with the social and political systems. Some are even employed in critical infrastructure sectors such as public transportation, education, municipal government and social security — positions that grant access to sensitive and privileged information.

MIT’s recruitment strategy relies heavily on a combination of pressure and reward. Potential informants are often offered financial incentives, protection for family members in Turkey, expedited travel arrangements, resolution of personal or family-related issues or access to lucrative government contracts. Conversely, those who resist may face veiled threats, arbitrary travel bans or fabricated criminal charges.

In extreme cases, sources say MIT has orchestrated the detention or imprisonment of targeted individuals as a means of breaking their resistance during custody.

In addition to launching recruitment campaigns targeting diaspora members visiting Turkey on vacation, MIT also focuses on dissidents already living in exile who fear returning to Turkey due to the risk of wrongful arrest. These include members of the Gülen movement — a group critical of the Erdogan government’s corruption and his administration’s ties to radical Islamist factions: Kurdish activists, leftist political opponents, exiled journalists and members of the Alevi religious minority.

In one recorded conversation shared confidentially with Nordic Monitor, a MIT operative attempted to recruit a Gülen-affiliated individual living in a Latin American country. The agent promised to drop all legal charges in Turkey and guarantee safe passage to visit family if the target agreed to provide intelligence on other movement members.

A similar pattern has been observed with critics in Europe and North America. Sources say MIT agents often reach out through family or mutual contacts, offering amnesty in exchange for cooperation. The Erdogan government considers many of these opposition groups to be “national security threats” and routinely brands peaceful dissenters as terrorists — an accusation widely challenged by international human rights organizations and democratic governments.

MIT’s aggressive recruitment and espionage operations have raised red flags among foreign governments, prompting pushback and legal actions in several countries. In some cases MIT operatives and their local collaborators have been arrested, charged or expelled.

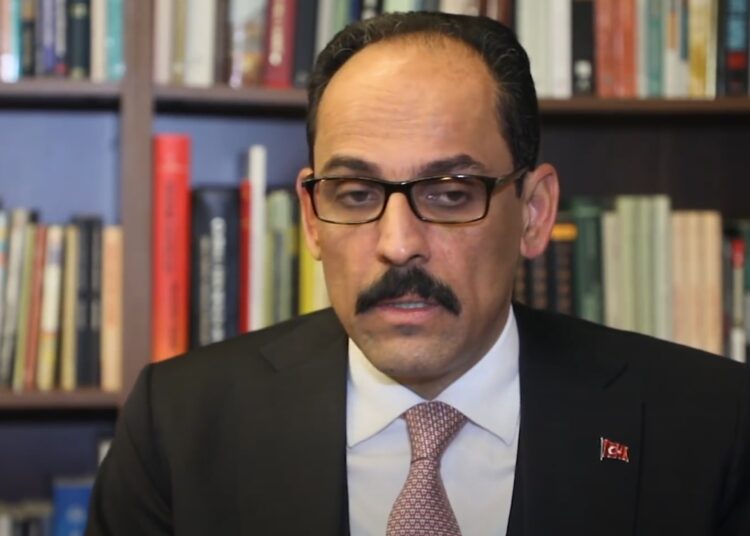

Despite growing international condemnation, the Erdogan government shows no signs of scaling back its overseas intelligence operations. On the contrary, President Erdogan has repeatedly vowed to “hunt down terrorists wherever they are,” using this rhetoric to justify increasingly aggressive intelligence activities abroad.

Erdogan frequently uses intimidation to maintain his repressive regime, deploying MIT to instill fear among opposition groups.

As MIT continues to expand its global footprint, many foreign governments are being forced to strengthen their counter-espionage efforts. Yet Turkey’s deeply embedded diaspora networks, combined with Erdogan’s tight control over state institutions, make accountability increasingly elusive. With no meaningful checks and balances remaining in Turkey to limit Erdogan’s power, MIT — which reports directly to the president — appears to operate with total impunity.