Levent Kenez / Stockholm

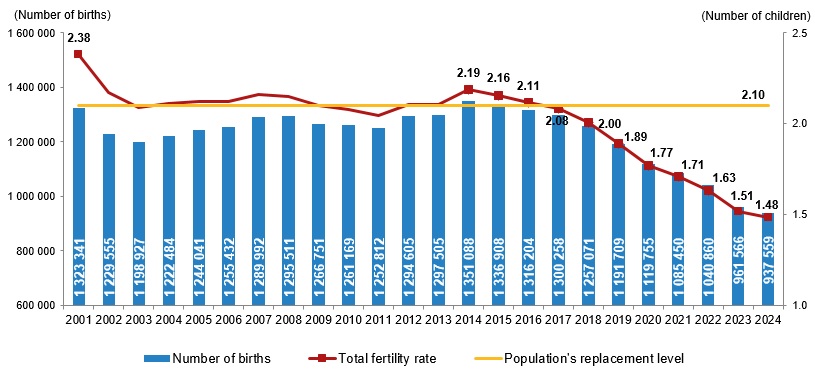

Turkey’s birth rate has plunged to its lowest level in modern history, prompting warnings from officials and experts, who say the country is facing a demographic crossroads. Recent data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK) show that the total fertility rate in 2024 fell to 1.48 children per woman, well below the population replacement level of 2.1 and a steep decline from 2.38 in 2001.

The number of live births in 2024 stood at 937,559, with boys accounting for 51.4 percent and girls for 48.6 percent. This marks a continuation of a trend that demographers and economists say is increasingly linked to economic hardship in Turkey, particularly among young adults of childbearing age.

A growing body of data suggests that economic anxiety is a significant factor driving the decline in fertility. A 2024 policy report by the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey (TEPAV) noted that persistent inflation, rising housing costs, job insecurity and declining real incomes have led many couples to delay or forgo having children. According to TÜİK’s 2023 Life Satisfaction Survey, 45.7 percent of respondents said their personal situation had worsened over the past five years, while only 23.9 percent said it had improved.

Additionally, the survey showed that only 23.9 percent of respondents were optimistic about their personal economic future, while over a third expected things to deteriorate further. Among people aged 25–34, the demographic most likely to start families, nearly 30 percent reported a decrease in income in the past year and 39 percent said they had to take on new debt.

The same TEPAV report noted that the average age of mothers at first birth has risen from 26.7 in 2001 to 29.3 in 2024, a shift attributed to delayed marriage, career prioritization and the high cost of childrearing.

During the International Family Forum organized by the government on May 23, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan rejected claims that economic pressures are to blame for declining birth rates. “Turkey’s fertility rate has dropped to 1.48. This is a disaster,” he said in a recent speech. “Yet some insist on blaming the economy. This is misleading.”

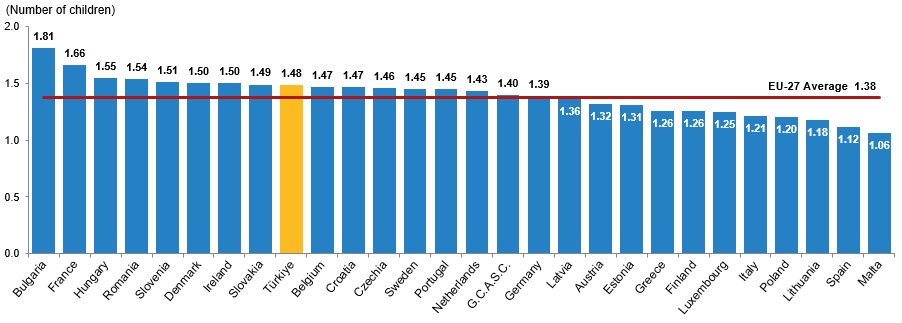

Erdoğan argued that Turkey’s fertility rate was higher when its per capita income was much lower and claimed that the decline stems from changing cultural values rather than material constraints. “Countries like Malta, with much higher income levels, have even lower fertility rates. The real issue is the rise of individualism and consumerism,” he added.

Family Minister Mahinur Göktaş previously warned during a live television appearance on April 19 that Turkey may struggle to find enough young people to serve in the military. “Our population aged 65 and over has surpassed 10 percent,” she said. “As the number of children declines, the population in need of care will continue to rise.”

Despite this stance, the government has launched a series of financial incentives aimed at reversing the trend. As of January 2025, Turkish families are receiving a one-time payment of 5,000 lira for their first child, 1,500 lira per month for their second child and 5,000 lira per month for the third and subsequent children. Payments are tax-free and administered through the Social Assistance and Solidarity Fund.

Fertility rates vary widely across Turkey. The southeastern province of Şanlıurfa reported the highest fertility rate in 2024 at 3.28 children per woman, more than double the national average. In contrast, cities like Bartın and Eskişehir recorded rates as low as 1.12.

These disparities reflect broader social and economic divides. Women with only basic or no formal education had a fertility rate of 2.65 in 2024, compared to just 1.22 among university graduates. Urbanization also plays a role. Densely populated urban areas recorded a fertility rate of 1.39 while rural areas saw rates closer to 1.83.

Turkey is not alone in facing demographic challenges. According to Eurostat, the average fertility rate in the European Union was 1.38 in 2023. Bulgaria had the highest rate at 1.81 while Malta had the lowest at 1.06. Turkey, at 1.48, ranked 9th among EU countries despite not being a member.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s demographic shift could have far-reaching consequences. Experts warn of a shrinking labor force, increased pressure on the pension system and an aging population. In 2024, 71 out of 81 provinces recorded fertility rates below the replacement level. In 2017, that number was just 57.

The average interval between the first and second child has also increased. In cities like Kırklareli and Çanakkale, mothers waited an average of 5.4 years between their first and second child. In Şanlıurfa, that gap was just 2.7 years.

Meanwhile, adolescent fertility, referring to births to mothers aged 15–19, has dropped dramatically from 49 per 1,000 in 2001 to just 10 per 1,000 in 2024. This indicates a significant societal shift away from early motherhood.

The Turkish government has responded to these trends with various policies, including expanding access to child care and offering new models for flexible work. Under the Family Year initiative launched in 2025, the state is also promoting marriage among young adults through a fund that offers interest-free loans of up to 150,000 lira for newlyweds who meet specific criteria.

Yet critics say these measures are insufficient or poorly targeted. “Without addressing the root causes, particularly economic insecurity and gender inequality, these incentives will not be enough,” wrote Merve Dündar, a policy analyst at TEPAV. She argues that structural changes are needed, including better parental leave policies, expanded child care infrastructure and labor protections for women.

Indeed, data show that despite rising participation in the workforce, many Turkish women still cite family responsibilities as a primary reason for not working. While female labor force participation rose to 35.8 percent in 2023, over 9 million women said they remained out of the labor force due to housework.