Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Following the pattern of past authoritarian rulers, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has made mass incarceration a central instrument of his governance. Under his rule the country has witnessed an unprecedented expansion of its prison system, with new facilities being rapidly constructed to accommodate the growing number of political prisoners, journalists, academics and activists accused of opposing the regime.

This calculated strategy serves multiple purposes: consolidating his grip on power, silencing dissenting voices and creating a climate of fear that discourages opposition. By weaponizing the judiciary and law enforcement, Erdogan has transformed the prison system into a tool of political repression, ensuring that critics — whether real or perceived — are effectively neutralized.

The latest official figures reveal a sharp increase in newly constructed, larger prisons under the guise of modernization, along with a soaring prison population — now the largest in Europe — which serves as a stark testament to this reprehensible policy, one that has received insufficient attention globally.

It is obvious that President Erdogan uses prisons not only to detain common criminals but also to imprison political dissidents, activists, journalists and perceived enemies of the state. The continuous influx of prisoners from these groups sustains the pervasive climate of fear under his regime, while the growing number of prisons nationwide sends a clear message to the population: Any form of defiance against his rule may lead to incarceration.

According to the latest figures released on March 3 by the Justice Ministry’s General Directorate of Prisons and Detention Houses (Adalet Bakanlığı Ceza ve Tevkifevleri Genel Müdürlüğü, CTGM), which oversees Turkey’s prisons, 398,694 people — both convicted and in pretrial detention — are currently incarcerated. With an official prison capacity of only 301,000, facilities are severely overcrowded, forcing prisoners to sleep on the floor, take turns to sleep in shifts and share limited bathroom facilities.

Prison population statistics in Turkey as of March 3, 2025, according to official data:

This figure also corresponds to a prison population rate of 466 per 100,000 people, a standard measure for incarceration. With this record-high number, Turkey ranks among the top countries in terms of imprisoning large numbers of people. When Erdogan came to power in 2002, more than two decades ago, Turkey’s prison population stood at 59,429, translating to a rate of 85 per 100,000 people. Under Erdogan’s 23-year rule, the prison population has skyrocketed by a staggering 571 percent between 2002 and 2025.

In the past decade the government has introduced several amnesty bills aimed at reducing the prison population, resulting in the release of hundreds of thousands of individuals, primarily common criminals, sex offenders, members of mafia and organized crime syndicates and people linked to jihadist groups. However, these amnesty measures excluded political prisoners, dissidents and critics — who belong to various groups subject to government crackdowns.

These amnesties were widely criticized as a sinister attempt to make room in prisons for more political prisoners. However, even this measure failed to curb the soaring prison population, as the government continued its relentless crackdown on anyone expressing critical views of President Erdogan’s policies.

In addition to those already incarcerated, as of February 28, the CTGM monitors 449,233 people who were either released on probation or subject to judicial supervision measures, such as regular reporting to a police station. In other words nearly half a million people outside of prison live under the constant threat of re-arrest and re-incarceration at any moment should authorities allege a violation of parole conditions.

Many political dissidents, journalists, activists and human rights defenders are part of this group. The constant threat of re-incarceration discourages them from participating in opposition movements, leading journalists to avoid critical coverage and forcing human rights activists to steer clear of cases that might incur the wrath of the Erdogan government.

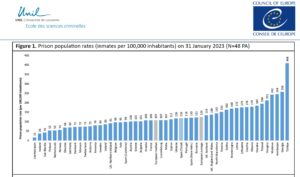

To better understand the severity of the situation in Turkey’s prisons in comparison to other countries, one might examine the Council of Europe’s (CoE) Annual Penal Statistics on Prison Populations, commonly known as SPACE I. The CoE’s latest report in 2023 reveals that more than a third of all prisoners in the CoE’s 46 member states are held in Turkey.

The report stated that as of January 31, 2023, the total number of inmates in European prisons was 1,036,680, with Turkey accounting for 348,265 of them. Following Turkey on the list were England and Wales with 81,806 inmates, France with 72,294, Poland with 71,228 and Germany with 58,098.

The data on the expansion of prisons and the billions of Turkish lira allocated to construct new and larger prison complexes further highlight how the Erdogan government uses incarceration as a key tool of repression in a country of approximately 85 million people. Justice Minister Yılmaz Tunç announced during a hearing of the parliamentary Human Rights Committee on June 12, 2024 that the government had built 299 new prisons, justifying this as a policy aimed at alleviating overcrowding and reducing prison density.

During the same hearing Enis Yavuz Yıldırım, the general director of the CTGM, provided more detailed figures on the prison expansion. He said there were 34 ongoing prison construction projects, 26 of which were in the active building phase. Of these, 16 were expected to be completed in 2024, eight in 2025 and two in 2026. With these additions, the total number of prisons in Turkey will rise to 437.

The Erdogan government has been generous in pouring billions into building and expanding penal facilities, allocating 8.7 billion lira for the construction of 36 new prisons over the next four years. In response to opposition criticism of the use of prisons as tools of repression, the government argues that it closed 394 old prisons as part of its efforts to modernize the country’s penal system. However, official data show that the capacity of those closed prisons was 41,923, while the newly built 299 prisons have a total capacity of 234,532.

The growing number of prisons and the rising prison population are not the only issues. The government also enforces restrictive and harsh policies in the prison system, limiting political prisoners’ rights to communicate with their families, access healthcare and education, consult with lawyers and appeal to both the Turkish public and the international community.

Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, a lawmaker and leading advocate for prison reform, told the Human Rights Committee that conditions in Turkey’s prisons are deplorable. He said prisoners are beaten and tortured and denied basic healthcare and that those who are seriously ill are left untreated. Early parole is arbitrarily denied, communication with families is restricted and political prisoners are often sent to prisons far from home, making it difficult for their families to visit.

“Turkey’s prisons rank first in the world for violations of the right to healthcare. In terms of overcrowding relative to its population, Turkey also holds the top position globally. It ranks first for the highest death rate in prisons worldwide and the highest suicide rate in prisons,” he told members of the Human Rights Committee during a hearing on June 12.

The Erdogan government often abuses the criminal justice system to target its critics and opponents, criminalizing legitimate dissent and even ordinary behavior. It specifically targets certain social groups with fabricated charges of terrorism, as seen in the massive crackdown on the faith-based Gülen movement, which has criticized the Erdogan government on a range of issues — from pervasive corruption in the administration to Turkey’s support of radicals and jihadists, both within Turkey and in its neighborhood.

The unprecedented expansion of prisons and the growing prison population in Turkey is not an anomaly but rather a calculated and deliberate strategy of Erdogan’s repressive regime. By increasing prison capacity and incarcerating more people, the Erdogan government reinforces its grip on power, eliminates political threats and intimidates the broader population.

There is no indication that President Erdogan will stop implementing this policy; in fact, recent developments suggest he may escalate it further. Amid growing discontent among the Turkish population and worsening economic hardship, Erdogan appears increasingly concerned about the viability and sustainability of his regime. In response, he may resort to even more fear-based tactics to maintain his hold on power.