Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Amid secret discussions among Turkish leaders about reconciliation with the Kurds, a public reference by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to the last Ottoman parliament’s declaration on national boundaries hints at a revival of expansionist ambitions. This vision appears to assert claims over territories in Syria, Iraq, Georgia, Cyprus and Greece.

“Let me make this absolutely clear: Our core policy is to protect the survival of our nation and ensure the highest level of peace, well-being and security for our 85 million citizens,” Erdogan stated in his October 19 speech, addressing neighborhood leaders (muhtars).

He quickly added, “Whoever threatens our homeland, we will not hesitate to act, regardless of who they are. We will not permit any intervention or alteration, whether on our 782,000 square kilometers of national territory or within the borders of the National Pact.”

The National Pact, or Misak-ı Milli in Turkish, comprises six resolutions made during the final session of the Ottoman Parliament on January 28, 1920, published on February 12 of that year. It outlined the envisioned borders of the Ottoman state. Shortly after the declaration, British forces occupied Istanbul, on March 16, 1920, and dissolved the Ottoman Parliament. However, the pact was later embraced by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, as a guiding principle for Turkish independence following World War I.

According to the Turkish Historical Society (Türk Tarih Kurumu, TTK), established by Atatürk as an official entity in 1931, a map created based on the principles of the National Pact includes territories in Georgia, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon, as well as the island of Cyprus, Greek islands in the Aegean and Mediterranean and parts of Greece’s Western Thrace region in southeastern Europe.

It seems that Erdogan’s scripted remark went largely unnoticed. This was certainly not an off-the-cuff comment, as he was reading from teleprompters. The statement was clearly deliberate, intended to highlight a long-held vision by the Turkish government.

The nine-page document prepared by the Turkish government’s historical society, Türk Tarih Kurumu (Turkish Historical Society), references territories in neighboring countries as part of the 1920 National Pact declaration, which was endorsed by modern Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk:

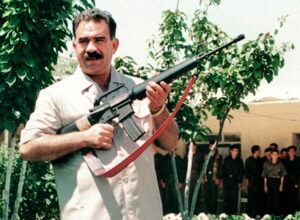

Erdogan and his allies believe that reconciliation with the Kurds, who are spread across Iran, Syria, Iraq, and Turkey, may help advance this vision. The fact that Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the primary negotiator for Kurdish reconciliation in Turkey, has made similar references to the National Pact in the past further bolsters the idea of irredentist ambitions harbored by Turkey.

Öcalan previously collaborated closely with Erdogan’s government during two unsuccessful peace initiatives. In a letter written from his prison cell and publicly read during the 2013 Nevruz celebrations, he declared that the era of armed struggle had come to an end. His message proposed a new political vision, emphasizing peaceful and equal coexistence for Turks and Kurds within the borders outlined by the National Pact.

According to the National Pact, territories not occupied at the time of the 1918 Armistice of Mudros, which ended hostilities between Ottoman forces and the Allied powers, were considered part of the Turkish homeland. The pact stipulated that the status of the provinces of Kars and Ardahan (now part of Turkey) and Batumi (now in Georgia), as well as Western Thrace (now in Greece), would be determined by local referendums. Additionally, the pact declared that the province of Mosul (now in Iraq) should be incorporated as a Turkish province.

Öcalan’s advocacy for a union of the Anatolian and Mesopotamian peoples, along with the unambiguous references to the 1920 National Pact, closely align with the Erdogan government’s ambitions to reclaim a greater role in the regions specified in the pact. While territorial annexation would prove difficult, it could nonetheless provide Turkey with strategic depth and de facto influence in certain areas mentioned in the pact.

A prime example of this is the autonomous regions controlled by Kurds in Iraq and Syria. President Erdogan has forged a close alliance with the Barzani family, which governs Iraqi Kurdistan. If negotiations with Öcalan prove successful, a similar relationship could be established with the autonomous region governed by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an offshoot of the PKK, in northeastern Syria.

The Turkish army currently occupies a stretch of territory near the Turkish border in northern Syria. If a settlement with the PKK yields a successful outcome, this region could potentially be merged with the areas controlled by the SDF in Syria.

The renewed discussions about the National Pact serve as a compelling narrative for the Turkish public, which has long been subjected to the official stance that Kurdish demands could ultimately result in the division of the country and the creation of an independent Kurdistan. The shared rhetoric of Erdogan and Öcalan regarding the pact may help to alleviate the deep psychological and historical trauma that many Turks feel over the loss of the empire and the subsequent national struggle to establish statehood after World War I.

In other words, the joint message conveys that peace with the PKK would not result in further fragmentation of the Turkish state or the establishment of an independent Kurdistan; rather, it would pave the way for a greater Turkey and an expansion of Turkish territories, even if achieving this physically proves to be challenging.

The deal between the PKK and the Turkish state does not yet appear to be fully finalized. The PKK’s recent targeting of the main facility of Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) in the capital of Ankara on October 23 that killed five people indicates that the group is seeking to gain more leverage for Öcalan during the final phase of negotiations. This tactic mirrors a similar pattern observed in past failed talks, where Öcalan secretly communicated with PKK commanders in Iraq through his lawyers to continue strikes, thereby enhancing his bargaining position in the negotiations.

In the past the immediate release of Öcalan from prison was a significant obstacle to reaching a settlement. The Erdogan government then proposed that his release be carried out in stages to avoid provoking a public backlash. However, this concern no longer seems to be an issue in the current discussions. A recent call by Devlet Bahçeli, Erdogan’s far-right nationalist ally, for the imprisoned PKK leader to speak in the Turkish Parliament — something previously deemed unthinkable — serves as a testament to this underlying agreement. “Let him [Öcalan] come and speak at the DEM Party [Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party, which serves as the political arm of the PKK] group meeting to declare that terrorism has ended and that the [PKK] organization has been dissolved,” Bahçeli said on October 22.

The primary bonr of contention in the recent talks appears to be the final status of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and how they will be factored into the overall settlement. The Erdogan government has long labeled the SDF and its military wing, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), as terrorist organizations and has frequently conducted attacks on Kurdish targets in Syria.

Moreover, American support for the SDF has consistently complicated Turkey’s bilateral relations with the United States. If this issue is resolved, it could provide significant political capital for the Erdogan government, allowing it to leverage this success internationally to expand Turkey’s influence over certain territories outlined in the 1920 National Pact. Such a settlement with the Kurds would likely be welcomed by the US, the UK and the European Union, securing their backing for some of the regional ambitions of the Erdogan government.

Let’s not forget that President Erdogan is open about his neo-Ottoman geopolitical ambitions. He has frequently lamented the concessions made by Turkish leaders after World War I, particularly regarding the Treaty of Lausanne, which established modern Turkey in 1923. Erdogan has entertained the idea of invading the Greek islands, threatened Cyprus with further action on the divided island, where the Turkish army has maintained a presence since the 1970s, and deployed troops to Syria, Libya and Azerbaijan to support pro-Turkish factions.

Although he has attempted to negotiate settlements with the PKK twice in the past, he ultimately abandoned these peace processes upon realizing that such agreements would not garner votes for his party and would not help him maintain power.

However, the political dynamics have now shifted. In the recent local elections, Erdogan lost major cities where Kurdish voters supported opposition candidates. Economically strained voters are defecting from his party, prompting him to reach out to the Kurds. The quickest way to achieve this is to secure the support of Öcalan and the main Kurdish political party DEM.

The third time could indeed prove to be the charm since Erdogan now finds himself in a stronger position. With full control over the levers of power in Turkey, a co-opted opposition and near-total dominance of the media, he is capable of selling almost anything to the Turkish public.