Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

NATO has long believed that Russia, supported by Belarus, will test the transatlantic alliance on the frontiers of Poland and the Baltic states using non-military/asymmetric actions as well as possible military actions that could lead to a military confrontation.

According to a secret NATO document obtained by Nordic Monitor, the alliance military planners concluded immediately after the first Russian intervention into Ukrainian territory in 2014 that a crisis could very well develop as a result of Russian aggression threatening the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Poland and/or Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

“The crisis leads to an increase in tension between Russia supported by Belarus on one side and Poland and/or Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania on the other, culminating in Russian non-military/asymmetric actions and possible military actions that could lead to a military confrontation,” the document states.

The document was developed as part of a NATO contingency plan called Eagle Guardian by the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and aimed to bolster the security of Poland and the Baltic states against the military power of Russia. It was signed by US Air Force General Philip M. Breedlove and submitted to the alliance’s leadership.

Secret NATO document on contingency planning in the face of the Russian annexation of Crimea was signed by US Air Force General Philip M. Breedlove:

NATO planners explained Russia’s political objectives as maintaining regime stability and cohesion, safeguarding the support of the Russian general public and ensuring Russia’s financial and economic viability. As for Moscow’s ultimate strategic goal, NATO concluded that Russia wanted to restore its “great power” status and strengthen its influence in neighboring countries, the so-called “near abroad,” which includes some NATO members.

The planners predicted that Russian military intervention in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 would encourage Russia to pursue its geopolitical ambitions more aggressively regardless of Russia’s condemnation by the international community. The recent military operations in Ukraine by Russian forces has proved that the planners were correct in their joint threat assessments and prediction of future Russian behavior.

“The Russian leadership has demonstrated a readiness and willingness to use force to achieve its strategic objectives. Russia’s policy and recent actions have therefore changed the strategic environment and pose a threat to those Allies bordering or in close proximity to Russia,” the document states.

Cover page of NATO’s Eagle Guardian Contingency Planning document:

The NATO planners also pointed out the weakness of NATO in terms of a slow decision-making process, in sharp contrast to what it called “the centralised Russian state model,“ which allowed Russia to plan, respond and act more quickly than the alliance and to rapidly concentrate forces.

Coupled with Russia’s demonstrated will to use military means in the advancement of its interests, this has enabled Russia to achieve early escalation dominance, the document explains. “The real dangers of the new Russian strategy are the ability to introduce sufficient ambiguity to make our decision-making difficult, and the ability to marginalise elements of the full spectrum of NATO’s current defensive capabilities,” the planners warned.

“Russia will continue to test and undermine the cohesion of the Alliance, particularly its collective defence, while seeking to avoid a direct military conflict with NATO,” the planners said, while warning that Russia’s posture towards NATO could change if a critical threshold were crossed.

NATO planners explained Russia’s political and strategic goals in triggering conflicts along the border with NATO member states:

The turn of events since the document was approved by NATO’s Military Committee has proved that the planners at NATO headquarters were correct in their predictions. Not only has Russia shown a willingness to use further military power to obtain its objectives, but it has also managed to drive a wedge between Turkey, governed by an Islamist party led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and NATO allies on a number of issues.

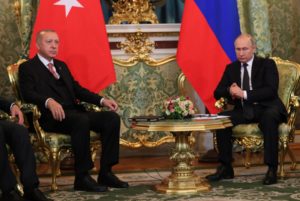

Turkey appears to be the weakest link in the alliance. The pace of political, commercial and military relations between Turkey and Russia increased with Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system despite warnings from the US and threats of sanctions. President Erdoğan also vowed to proceed with the purchase of a second batch of S-400 missiles from Russia. The Erdoğan government also gave Russia a major contract to build the Akkuyu nuclear power plant and fast tracked approval procedures for the TurkStream pipeline, which is set to deliver natural gas from Anapa in Russia to Europe through a subsea pipeline that links to Turkey via the Black Sea.

Even before the hostilities started, Turkish officials had more to say on the West, with Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu accusing the US and allies of raising the threat of military intervention on Russia’s part prematurely. He said Turkey did not see attacks to be imminent, which turned out to not be the case.

Once the Russian military action was launched. Turkey’s stance also diverged from that of its Western allies, declining to describe the Russian military operation in Ukraine as an invasion and expressing its opposition to sanctioning Russia. While Turkish officials joined the statements of condemnation of Russia and supported the territorial integrity of Ukraine, they also did not hesitate to direct criticism at NATO and the West.

On February 23, President Erdoğan called Russia a friend with deep historical ties; accused NATO and the EU of lacking a serious determined stance; and mocked NATO allies for what he said was merely giving advice to Ukraine. At the outset of the conflict, Ankara refused to implement Kyiv’s request for closure of the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, linking the Mediterranean and Black seas, to Russia, saying it was considering options under the 1936 Montreux Convention. Mesut Hakkı Caşın, a member of the Presidential Board for Foreign Policy and Security, said on CNN’s Turkish affiliate on February 25 that Turkey would act according to its own interests rather than those of NATO, rebuked Ukrainian Ambassador to Turkey Vasyl Bodnar for talking to the press about the Turkish straits and accused of him speaking on behalf of other countries.

On February 25, Turkey also abstained in a vote at the Council of Europe to suspend Russia from the council, Europe’s largest intergovernmental organization, which champions the rule of law, fundamental freedoms and human rights.

Apparently pressured by its NATO allies, Turkey changed its rhetoric on February 27 and decided to describe the hostilities as a war, which means Turkey can limit the passage of warships through the straits during wartime or if threatened. Nevertheless, the convention does not allow Turkey to bar Russian or Ukrainian ships from using the straits when they are returning to the naval bases where they were originally anchored.