Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

As part of an escalating campaign of intimidation of critics, opponents and dissidents, Turkish authorities have issued nine arrest warrants for Turkish soccer legend Hakan Şükür, a retired striker for the Galatasaray football team and former politician.

According to official documents dated July 12, 2021 obtained by Nordic Monitor, Turkish prosecutors are seeking the arrest of Şükür, a resident of the US, for defamation and terrorism, the two most abused criminal charges used by the government of Islamist President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to stifle dissent, suppress opposition voices and crack down on freedom of expression.

The 50-year-old top goal scorer in the Turkish Super League became a target of President Erdoğan, then the prime minister, when he resigned from the ruling justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2013 in protest of government interference in major corruption probes that incriminated Erdoğan and his inner circle.

On the day the popular star resigned he was offered a ministry post by the government to buy his silence and prevent his departure, but he rejected it and left the party. As an independent lawmaker, Şükür then became a vocal critic of Erdoğan and his government policies. In the meantime, Erdoğan managed to stifle the graft probes despite overwhelming evidence of corruption exposed to the public after the removal of the police chiefs and prosecutors who conducted the investigation.

Official document details nine arrest warrants issued for legendary Turkish soccer player Hakan Şükür on dubious charges:

Şükür’s opposition came with a cost, however. Under Erdoğan’s orders, his contract with the government-controlled Lig TV, where Şükür had been giving soccer commentary, was abruptly terminated on January 2, 2014. Şükür’s name was also removed from a stadium in İstanbul’s Sancaktepe district in April 2014. The venue, run by the Sancaktepe Municipality, which was under the control of Erdoğan’s party, was opened in 2010 and given the name Hakan Şükür Stadium.

What is more, loyalist prosecutors launched multiple criminal investigations into him on bogus charges and dubious evidence as part of scaremongering tactics. Nearly half the outstanding arrest warrants for him are based on alleged defamation of President Erdoğan.

The Stockholm Center for Freedom reported in March 2021 that Turkish prosecutors investigated 128,872 people for insulting Erdoğan between 2014 and 2019, resulting in prison sentences for nearly 10,000 people with many cases still pending. The crackdown targeted 318 minors between the ages 12 and 17 who have been the subject of criminal investigations for insulting the head of state.

Article 299 of the Turkish Penal Code (TCK) states that any person who insults the president of the republic faces a prison term of up to four years. This sentence can be increased by a sixth if it has national exposure, and by a third if committed by the press or media. In total 9,554 people have been handed down sentences for insulting the president.

Unlike Erdoğan, former presidents rarely used allegations of slander in criminal complaints against critics and opponents. The huge spike in defamation cases under Erdoğan’s tenure drew the attention of European inter-governmental organizations as well.

In a 2016 opinion the Venice Commission, the Council of Europe body specializing in constitutional matters and the rule of law, sounded alarm bells on the abuse of defamation charges. It noted with concern the large number of investigations, prosecutions or convictions reported by the press for insulting the president.

The European Commission also highlighted the abuse of slander charges by President Erdoğan in its 2015 report and said, “There is a widened practice of court cases for alleged insult against the President being launched against journalists, writers, social media users and other members of the public, which may end in prison sentences, suspended sentences or punitive fines.”

Some of the warrants were issued by investigating judges who run special project courts called the Penal Courts of Peace ( Sulh Ceza Hakimlikleri, SCH) in Istanbul. The SCH courts were the idea in 2014 of President Erdoğan, who called it a special project to hunt down his critics. The benches of SCH courts are staffed by partisans and loyalists who act in line with Erdoğan’s wishes.

Some arrest warrants issued for Şükür originated from terrorism charges because of Şükür’s support for jailed journalists. In 2015 he and another lawmaker faced charges of “membership in a terrorist organization” and “putting organized pressure on public officials” when showing their solidarity with imprisoned journalist Hidayet Karaca.

Other charges stem from his alleged affiliation with the Gülen movement, a civic group that is critical of the Erdoğan regime. The movement is inspired by Turkish Muslim scholar Fethullah Gülen, a US resident and a fierce opponent of the Erdoğan government on a range of issues from pervasive corruption in the administration to Turkey’s aiding and abetting of armed jihadist groups.

Erdoğan’s government branded Gülen as a terrorist in 2014, immediately after major corruption investigations that incriminated Erdoğan, his family members and political and business associates were made public in December 2013. He accused Gülen of instigating the corruption probes, a claim that was denied by Gülen.

The Turkish president also accused Gülen of orchestrating a 2016 coup attempt that in fact helped Erdoğan consolidate power, dismantle the rule of law, sideline the parliament and remove checks and balances on his rule. Gülen denied having any role in the putschist attempt and asked for an international probe, a request that was rejected by Erdoğan. The government has failed to present any evidence proving Gülen’s complicity in the abortive putsch.

Many believe the failed coup was a false flag operation orchestrated by Erdoğan and his intelligence and military chiefs to set up the opposition for a crackdown. During coup trials, evidence emerged that many operatives of the intelligence agency had worked to make the limited military mobilization appear to be a real coup attempt.

A total of 292,000 people affiliated with the movement have been detained, while 96,000 others have been jailed in the last five years according to figures announced by Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu in September.

According to statistics released by the Council of Europe (CoE), as of January 2020 out of 30,524 prisoners convicted on terrorism charges in the 47 CoE member states, 29,827 were in Turkey. In other words, 98 percent of all inmates convicted of terrorism in all of Europe are resident in Turkey. It shows how the government abuses its counterterrorism laws to punish critics, opponents and dissidents in this country of 84 million that is suffering under the iron grip of President Erdoğan.

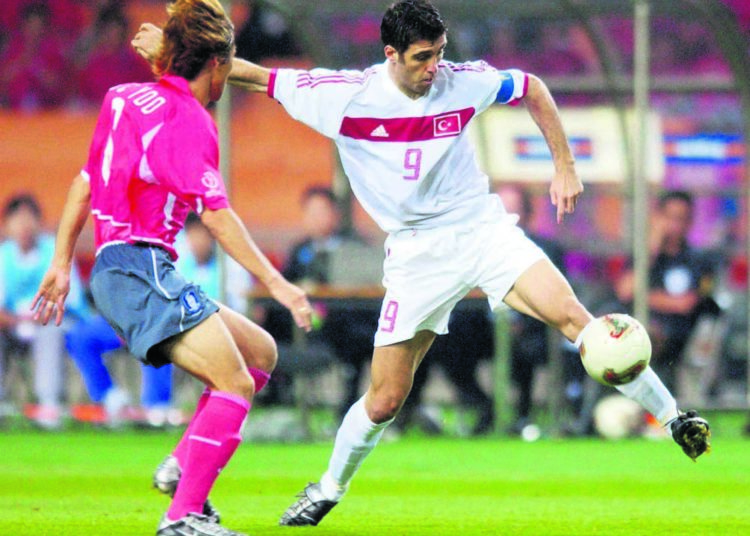

Şükür had an outstanding football career and is recognized as the Turkish national team’s all-time top goal-scorer. Called the “Bull of the Bosporus” in Turkey, he is best known internationally for having scored the fastest goal in World Cup history in 2002. Şükür scored in the 11th second of a match against South Korea in 2002, the fastest goal in World Cup history, a record that still stands today.

He received the Football Legends — Golden Foot Award 2014 at Monaco’s Monte Carlo Bay Hotel and Resort on October 11, 2014, where he left his footprints on the Champions Promenade, just as movie stars leave their handprints in Hollywood. He was selected as one of the Golden Foot Legends alongside greats such as former Belgium goalkeeper Jean-Marie Pfaff, prolific Cameroon forward Roger Milla, Czech Republic’s Antonin Panenka, of the eponymous Panenka penalty kick, Japan’s Hidetoshi Nakata and the first woman to be given the award, American Mia Hamm. According to a press release issued by the Golden Foot Award Monaco committee, the award was bestowed on Şükür due to his outstanding career.

In March 2015, the FIFA World Football Museum, established by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), offered to feature some of Şükür’s photographs, personal belongings, documents and items from his youth. Speaking to the press at the time, Şükür said he was informed about FIFA’s decision by Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) Vice President Şenes Erzik. “I am planning to give them my uniform that I wore in the UEFA Cup final in 2000 against Arsenal and the shoes that I wore in a match against South Korea in the 2002 World Cup,” Şükür said.

A short experiment with politics between 2011 and 2013 featured him as a lawmaker who was trying to use his global connections to forge better relations between Turkey and other countries. Boasting his Albanian ethnic heritage, Şükür, a key figure in the Albanian community in Turkey, led the Turkish-Albanian inter-parliamentary friendship group.

He was later elected chair of the Turkish-Italian friendship group. Şükür, who speaks Italian, was formerly a player for Italian clubs Torino, Inter and Parma. In the end, it appears he did not like politics and was irritated by what he had witnessed. He ended up resigning in protest of party politics and corruption in Erdoğan’s government. He moved to the United States to escape false imprisonment and currently lives there with his family.