A jihadist imam on the Turkish government payroll played an instrumental role in the radicalization and training of an al-Qaeda-linked police officer who assassinated the Russian ambassador to Turkey in Ankara in December 2016. Yet, the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan did not bother to investigate this radical imam and kept him running a mosque in the Turkish capital.

Nordic Monitor’s investigation has identified this radical cleric as Recep Uğuz, who also goes by the name Ebu Huzeyfe Turki, a 47-year-old man from a village called İmamlar located near the town of Çameli in Turkey’s western Denizli province. He works for the government’s religious service arm, the Diyanet (Religious Affairs Directorate), in Ankara’s Yenimahalle district, where the National Intelligence Organization (MİT) maintains its headquarters. With a monthly salary from government coffers, Ebu Huzeyfe raises a large amount of money not only through a privately run network of associations and foundations but also from the Diyanet’s multibillion-dollar foundation, the Diyanet Vakfı, for which he had worked in 2013 and 2014.

Ebu Huzeyfe’s journey started in 1993 in Sudan, a crossroads of many extremists including Osama bin Laden, who lived in Khartoum between 1991 and 1996. He was enrolled in the International University of Africa, a magnet for radical students from abroad, while staying at Bayt al-Shabab (the house of youths) with other radical students from various countries. He was personally trained by a battle-hardened Algerian jihadist named Abu Saleh Lakhdar al-Jazairi, a Salafist, between 1993 and 1994 in the Rumaila district of southern Khartoum. Abu Salah was detained in Libya after he fled Algeria with another jihadist named Kamal, a French citizen, but managed to escape to Sudan. Ebu Huzeyfe also befriended people who joined Sudan’s paramilitary Popular Defence Force (PDF) militias (al-difa al-shabi) against South Sudan.

He describes himself as a student of Muslim preacher Mahmud Esad Coşan, who had led a religious congregation called İskenderpaşa until his accidental death in Australia. In recent years the İskenderpaşa sect has grown to be very influential within the Turkish government and staffs many key positions with the help of Erdoğan. Ebu Huzeyfe personally met with Coşan, who came to Sudan to disburse cash to his affiliates and to attend a religious gathering in July 1994.

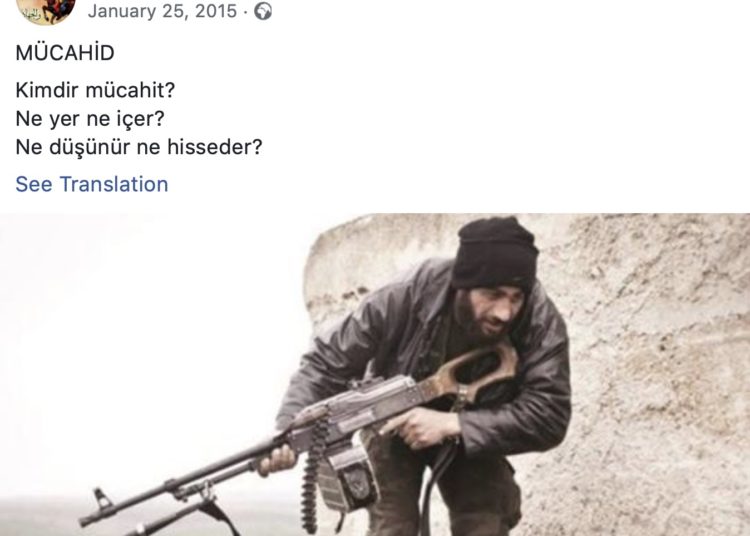

Although he has differences with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), Ebu Huzeyfe nevertheless supports these groups and other jihadists against what he calls infidels. Calling ISIL his “bad brothers,” he declared he would back them against the enemies of Islam. In October 2014 he urged that ISIL be supported against “Marxist” Kurds, who are the enemies of Islam. In September 2014 he wrote “Today I’m ISIL, tomorrow I’m Jabhat al-Nusra” while calling on his followers to support ISIL. When radical preacher Abu Hanzala (Halis Bayancuk), who inspired Turkish youths to join jihadist groups including ISIL, was detained in July 2015, he wrote that the government had made a mistake and said Abu Hanzala was a very good Muslim. He claimed ISIL followers and militants are pure, clean Muslims who have good intentions but that the ISIL leadership was being corrupted by the Americans.

In 2011 he predicted Turkey would expand into Iraq and Syria by grabbing more territory and claimed the prediction had come true in 2016 when the Turkish army entered Syria. Ebu Huzeyfe has expressed his radical views in a collection of writings over the years on his own blogs, which were taken off the grid after the assassination of the Russian ambassador. His writings, obtained by Nordic Monitor, portray an extremist preacher who would see no problem in taking up arms against the West, Russia and others in the name of jihad and would endorse jihadist groups from ISIL to al-Qaeda.

Married twice, once in Sudan to a Muslim convert from Uganda, then to a Malay who settled in Japan, Ebu Huzeyfe has made many trips to foreign countries including Syria, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Japan. He was hired by the Turkish government’s Diyanet as an imam in July 2011 and began preaching and leading prayers in Ankara, where he became acquainted with the Russian ambassador’s killer, a radicalized Turkish police officer. He now leads prayers in the Özelif Mosque in the Demetevler district, once preached in by his mentor Coşan.

In his witness testimony to the Turkish police, given on December 27, 2016, Ebu Huzeyfe admitted that he knew Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş, the 22-year-old riot police officer who gunned down Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov. According to his statement, the policeman came to his mosque one Sunday morning in mid-2015 to attend prayers along with 30 to 40 young men. Altıntaş and his roommate Sercan Başar, who is also a police officer and a suspect in the Karlov case, asked Ebu Huzeyfe to give them private Arabic lessons, to which the cleric agreed. Altıntaş’s broken Arabic chants of a jihadist song after the murder of the ambassador came from the lessons he received from Ebu Huzeyfe.

Altıntaş and Başar frequented Ebu Huzeyfe’s mosque and later joined meetings privately organized by a religious sect, the Mahmut Esat Coşan group in Ankara. Hasan Tunç, a police officer who is also a suspect in the murder of the Russian ambassador, was also among the participants, according to Ebu Huzeyfe. The police officers attended meetings until mid-2016, when Ebu Huzeyfe went on pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia, on August 6, 2016, and later joined his family, who were vacationing in Malaysia, his wife’s homeland.

On the evening the assassination took place, Ebu Huzeyfe said he went to attend a meeting held at an Islamist youth association called the İnsanlığa Hizmet Gençlik Spor ve İzcilik Kulübü. The association is led by Ebu Huzeyfe’s colleagues, and the board members were listed as Yavuz Kocamış (president), Muhammed Zengin (vice president), Mehmet Sait Yavuz, Muhammed Esad Polat, Hidayet Zahit Gürbüz and Ali İhsan Güneşer. Kocamış is the head of the Directorate of Branches at the Diyanet Foundation, which controls billions of dollars of assets in Turkey and abroad.

Shockingly, Turkish prosecutor Adem Akıncı, who investigated the murder and drafted the indictment, did not see any problem with this radical cleric who had very close ties to the killer. In fact, in his testimony the cleric said one of his students named Muhammet Sait Kara phoned him on the night of the murder and told him that the assassin, Altıntaş, came by the mosque on Dec. 19 at around 8 or 9 a.m. [the murder took place in the evening]. Claiming that his phone battery had run out, Altıntaş borrowed Kara’s phone to make some calls. The two later had breakfast, and Altıntaş left. The cleric Ebu Huzeyfe also added that he wanted to consult with some people first before testifying as a witness. Kara, a theology student who was staying in a lodge next to Ebu Huzeyfe’s mosque, also testified as a witness in the case and said the same thing.

Ebu Huzeyfe’s statement was taken again on January 24, 2017, and he was asked about the Arabic lessons Altıntaş had taken from him. The cleric said he only taught introductory lessons in Arabic to the assassin and denied teaching him the slogan the killer recited after the murder. In his second testimony, he described the group of 30 to 40 young men that came to his mosque in mid-2015 as being affiliated with the Social Fabric Foundation (Sosyal Doku Vakfı), an Islamist NGO run by another jihadist cleric, Nurettin (Nureddin) Yıldız.

Yıldız is often described as the family cleric of Erdoğan, parading as the keynote speaker at both youth events organized by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and conferences and lectures sponsored by the Turkey Youth Foundation (TUGVA), which is run by Erdoğan’s family. He even travelled to Syria to meet with militant groups and often preached in support of violent jihadist campaigns around the world. The killer joined Yıldız’s volunteer group in Ankara, the Sosyal Doku Ankara Gönüllüleri Grubu (Social Fabric Ankara Volunteers Group) in 2014.

The prosecutor should have followed the leads and looked into the background of Ebu Huzeyfe and his associates. He must have been listed as a suspect in the case, not as a witness, yet he was clearly protected by the prosecutor. Perhaps he has links to powerful figures in Turkey’s security and intelligence apparatus. The same can also be said for the other radical cleric, Yıldız. Despite attempts by the Islamist government in Turkey to hush up the investigation into the assassination of Russian Ambassador Karlov and falsely charge people who had nothing to do with his murder to divert attention, there are still some serious clues left in the indictment that help trace the footsteps of the masterminds and instigators that radicalized the Turkish police officer who killed the Russian envoy.