Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Turkish intelligence agency MIT infiltrated a leftist militant group in Switzerland using a resident-turned-asset there, monitored the group’s recruitment, fundraising and terror plots but did not share the information with Turkish law enforcement agencies or judicial authorities.

In a damning statement to the police on December 6, 2011, 41-year-old Murat Şahin (aka Bayram), a long-time resident of Switzerland, revealed everything he had done for MIT in Swiss territory, where his handler operated in disguise out of the Turkish Embassy.

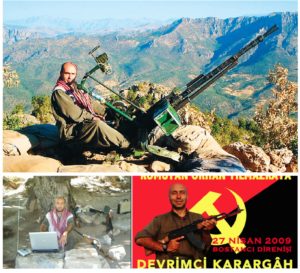

Some time in 2010 MIT asked Murat to infiltrate leftist terrorist group the Revolutionary Headquarters (Devrimci Karargah, or DK), a Marxist-Leninist organization that was involved in drug trafficking, illegal arms trade, gambling and prostitution according to the details of the case file in Turkey.

Murat managed to gain the trust of key DK figures in Switzerland, connected with their operatives in Turkey and Iraq where DK had secret cells and passed all the information he collected to MIT. Yet none of the vital intelligence tips obtained by the agency was shared with the police, the main law enforcement agency in Turkey, or judicial authorities, who had already been investigating the group in a counterterrorism probe.

Cover page of the statement made by Murat Şahin in Turkey:

In fact, according to Murat’s statement, MIT even facilitated the communication among DK cells in Switzerland, Turkey and Iraq. The intelligence agency did not act when DK recruited new operatives and moved them across Turkish borders illegally, funneling cash to its operatives in order to fund the group’s activities. MIT handlers instructed Murat to keep information from the police if he got caught. On one occasion MIT even alerted him to flee a crackdown when it learned that the police would launch an operation against DK cells.

Murat was no stranger to MIT when he was recruited by the agency. His father, Yasin Şahin, who had been involved in various militant leftist groups in Turkey before settling in Switzerland, also worked with Turkish intelligence and fed information to his handlers from within. Through his father’s connections Murat was familiar with several militant organizations in Switzerland. He had been responsible for the external relations of the Maoist Communist Party (MKP), listed as a terrorist group in Turkey, for years.

According to his statement, Murat experienced a falling out with the MKP over personal disputes with other members in 2005 and decided to work with the Turkish Embassy. Mutlu Büyükbay, a Turkish intelligence officer working under the cover of a diplomat at the Turkish Embassy in Bern, recruited him as informant. He was paid a monthly allowance of up to 600 Swiss francs between 2005 and 2011 and was provided with two phones for secure communication.

In 2009 Büyükbay was replaced by MIT agent Ali Doğan, who was the new handler working as a diplomat at the embassy. He was gathering information about leftist militant organizations, their members and finances and passing it to MIT. He even took the contact list from his father’s phone and shared it with the agency.

According to Yasin, the the Marist-Leninist Liberation Party (MLKP) had an organization called the Switzerland Immigrant Workers’ Federation (Föderation Der Immigrierten Arbeiter In Der Schweiz, or İsviçre Göçmen İşçiler Federasyonu, İGİF) and an affiliated entity, Bildung und Kultur Zentrum Zürich (Zürih Eğitim ve Kültür Merkezi, or the Zurich Education and Culture Center). The MKP runs the Föderation für Demokratische Rechte in der Schweiz (Switzerland Democratic Rights Federation, Isviçre Demokratik Haklar Federasyonu or İDHF), and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) had an organization called the Federation of Kurdish Associations in Switzerland (Kültür Derrnekleri Federasyonu, or FEKAR).

In 2010 the agency asked him to collect information about the DK, whose leader, Orhan Yılmazkaya, was killed in a shootout with the police in the middle of İstanbul on April 27, 2009. The DK was already under investigation in Turkey, with the police trying to identify its operatives and prosecutors gathering evidence to file an indictment against its members.

Under a new assignment Murat discovered that a man he had known as Faruk (real name Şemdin Şimşir) since 1996 was in charge of the DK in Switzerland. Under the pretext of purchasing a ticket to a commemoration event for slain DK leader Yılmazkaya, he managed to meet Şimşir and was able to gain his trust. In time he was given assignments such as running DK publication the Revolutionary Front (Devrimci Cephe) in Switzerland. He was clearing all his moves with MIT in the meantime.

He learned that the DK was financed by a man named Şişman who ran a brothel in the German city of Stuttgart.

Full text of Murat Şahin’s statement to the Turkish police:

Şimşir, now 56, had been going back and forth between Switzerland and Iraq, where the DK had five or six members trained at a PKK-run base in the Zap region of Kurdistan. Yasin was also asked whether he was willing to travel there, but he declined, citing family reasons, when MIT told him to turn down the offer.

In April 2010 Yasin went to Turkey to take part in the May 1 Labor Day protests and asked Şimşir to arrange a meeting with local DK militants there. Şimşir told him to drop by the Revolutionary Front magazine bureau in Istanbul’s Taksim district and act in line with their guidance.

MIT agent Doğan called him from Switzerland while he was in Istanbul and said MIT headquarters wanted him to go to Ankara. A man picked him from a park after his arrival in Ankara and took him to a house where a woman, 50 or 60 years old, greeted him. He was told the woman was an intelligence chief for MIT responsible for monitoring all leftist groups in Turkey.

“Not everyone can come here easily, you’re only the third person. I don’t meet with everyone,” the woman said. “This matter is special. You don’t need to be afraid, the [Turkish] state and we [MIT] are behind you,” she said, Murat recalled of the conversation. “I was told to not give any statement in the event the police detained me,” he added. He was given 500 euros in cash, and MIT let him go back to Switzerland.

The next year, he went back to Turkey again to attend the May Day rally in Istanbul but changed his plans at the last minute after a cryptic phone call from Doğan, who said, “Do not go to the picnic tomorrow.” When he returned to Switzerland, Doğan told him MIT had learned about a police raid on DK members and that the agency did not want him to get burned in the crackdown and did not want MIT in trouble with law enforcement and the judicial authorities.

Murat also learned that the PKK wanted to cooperate with the DK in expanding into the Black Sea region in the north of Turkey, a stronghold of Turkish nationalists, which made it nearly impossible for the PKK to operate in such a hostile environment. The DK promised to facilitate the PKK actions in that region according to Şimşir, who met with Cemil Bayık, a senior PKK commander. Bayık told Şimşir that both the PKK and the DK shared the same fate and that one cannot survive without the other.

As part of his assignment Murat also acted as a courier conveying secret messages from Switzerland to DK militants in Turkey, doing so with the approval and knowledge of the Turkish intelligence agency. On December 3, 2011, when he landed in Istanbul, he was greeted by MIT agents Irfan Aküzüm, Hüseyin Uğur and Nihat Topçu, who took a copy of the DK message, sealed it again and instructed Murat to deliver it to a DK militant named Volkan Karakuş (aka Vural) in Turkey. When the meeting took place, Vural told him he had recruited a young man who wanted to enlist with the DK and go to the military training camp in northern Iraq.

leftist Revolutionary Headquarters group in April 2009 and detained dozens of suspected members.

Two days later, on the day of his return, he met a MIT agent again at the airport to hand over the telephone he picked up when he first arrived in Turkey. After the meeting the police detained him when he was checking in. He was already flagged by the police when his phone conversation with DK militant Bayram Akadoğdu (aka Ali Haydar) was intercepted. The wiretaps, obtained with a court authorization as part of a criminal probe into the DK, showed him engaging in illegal activities on behalf of the DK.

Murat told the police that he had his own suspicions about assignments he had with MIT and noticed on several occasions that the critical information he passed to the intelligence agency did not result in a police crackdown or the thwarting of a DK plot. The information and contact details of the DK leaders he obtained and passed on to MIT did not result in any police action or prosecution, he said.

According to Murat the DK had nothing to with leftist revolutionary ideas, which were protected by powerful people in branches of Turkish state security and even had some international support. The DK was involved with drug trafficking, prostitution and gambling. He said MIT already knew that a DK militant named Rayif Demir (aka Terzi Rauf) was running an illegal drug and arms trade on behalf of the organization in Europe.

He said other Turkish leftist groups view the DK suspiciously and shy away from working together with it. He pointed out that Şimşir has no leadership skills to run the organization because he was a heavy drinker and suffered from psychological problems. At one time he even tried to commit suicide by shooting himself in the head, Murat claimed.

The prosecutor’s office had to separate Murat’s case from the DK case file under pressure from the government, which had changed the intelligence bill in 2012 to provide broader immunity for MIT agents from criminal prosecution. With a new amendment, the prosecution of MIT agents under the penal code required the permission of then-Prime Minister and current President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In most cases, the government did not allow the prosecution of intelligence officers even if they were clearly involved in breaking the law. Saved from legal troubles Murat, who was briefly jailed, returned to Switzerland.

In Switzerland Murat was questioned by Şimşir about allegations that he was connected to MIT. He lied and denied the reports. Şimşir asked for proof and wanted to see his statement. The MIT agent at the Turkish Embassy did not help, saying he was awaiting instructions from headquarters on how to proceed. On May 22, 2012 he went to Turkey again to plead with the police to delete parts of the statement in which he had revealed his work for MIT and asked them to take a new one, but the police said it couldn’t do what he was asking.

In a secret letter to the Istanbul prosecutor’s office, the Turkish intelligence agency acknowledged Murat’s work for the agency and revealed the names of intelligence officers in Switzerland who had worked with him:

According to Murat his father Yasin also worked for MIT in the old days, passing on the intelligence he collected from the leftist militant organizations in Turkey and abroad. Yasin was first active in a faction of the Turkish People’s Liberation Party-Front (Türkiye Halk Partisi/Cephesi in Turkish, THKP/C). The faction called Third Way/Resistance (Üçüncü Yol/Direniş) was led by Hamza Yalçın, a lieutenant who was dismissed from the Turkish military.

Yasin’s handler at the intelligence agency was a man named Yunus Akter, who protected him when he was in trouble with the law. According to his son Yasin was involved a in an exchange of gunfire with the police and fled the scene when his comrade Halil Ateş was wounded during the clashes. MIT agent Akter cleaned up the documentary evidence at the crime scene, preventing Yasin from being discovered by the police as a MIT operative.

Later, Yasin joined the Turkish Communist Party/Marxist Leninist (Türkiye Komünist Partisi/ Marksist-Leninist, TKP/ML) and the Turkish Workers and Peasants’ Liberation Army (Türkiye İşçi Köylü Kurtuluş Ordusu, TİKKO). He continued to pass intelligence to MIT until he left the country in an illegal border crossing in 1985 or 1986 and eventually settled in Switzerland.

When he flew back to Turkey on July 2, 1993, the police detained him at the airport on an outstanding arrest warrant. But his handler Akter came to his rescue and freed him from police custody. With help from MIT, Yasin took a job at the Sabancı Center, a commercial building that is home to one of Turkey’s major conglomerates led by the wealthy Sabancı family. He worked there as the director of a cleaning crew until 1995.

Yasin took his family back to Switzerland in 1995, but his contacts with MIT continued. His elder son Cengiz Şahin at one time was in charge of a unit of the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) in 2000 and 2001 and also applied to work with MIT. The DHKP/C is listed as a terrorist organization by the EU, the US and Turkey.