Levent Kenez/Stockholm

Spain’s record seizure of nearly 10 tons of cocaine from a cargo ship in the Atlantic Ocean has reignited questions about Turkey’s declared fight against narcotics, drawing attention to a pattern in which suspects are arrested in headline-grabbing operations but later released or acquitted often without convictions linking them to drug trafficking.

On January 11 the Spanish National Police and Navy intercepted Cameroonian-flagged vessel the United S in international waters roughly 535 kilometers southwest of the Canary Islands. Hidden among a shipment of salt, officers found 9,994 kilograms of cocaine packed into 294 bundles. Spanish authorities said it was the largest single cocaine seizure ever recorded in Europe.

The ship, which had departed Brazil and was sailing toward a European port, was stopped after surveillance detected suspicious activity, including speedboats approaching the vessel, a method commonly associated with narcotics transfers at sea. All 13 crew members aboard the vessel were arrested. The detainees included four Turkish nationals as well as citizens of Serbia, Hungary and India. The vessel was subsequently towed to the port of Tenerife. Spanish officials said the operation, code-named “Marea Blanca,” or “White Tide,” involved cooperation with law enforcement agencies from the United States, Brazil, the United Kingdom, France and Portugal.

The case quickly extended to Turkey after reports indicated that the United S was linked to a Turkey-based shipping company. The Istanbul Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office announced that it had launched an ex officio investigation, noting that four of the detained crew members were Turkish citizens. Turkish police conducted simultaneous raids at 19 locations across six provinces including İstanbul and Mersin and detained seven suspects on charges of forming a criminal organization, drug trafficking and laundering criminal proceeds.

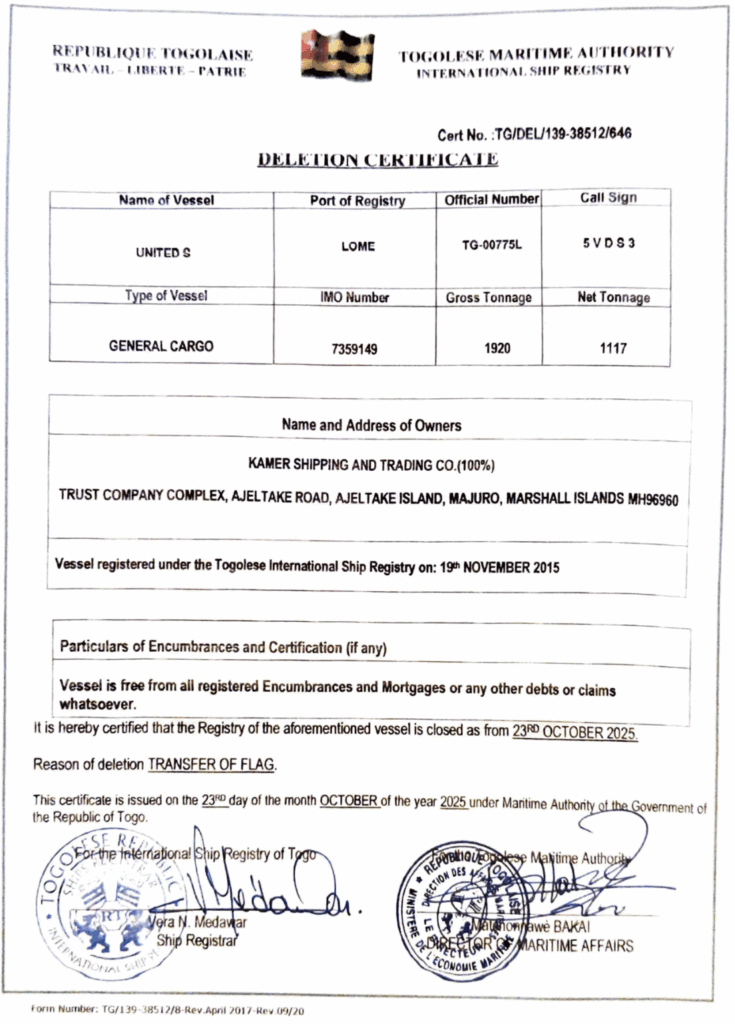

Prosecutors ordered the seizure of assets belonging to several suspects and to United Shipping, also known as Kamer Shipping & Trading Co., including bank accounts, real estate, company shares and cryptocurrency holdings. Three additional suspects were reported to be abroad and the subject of arrest warrants. The four Turkish crew members detained aboard the ship remain in custody in Spain.

As details emerged, Turkish media reported that the cocaine shipment was allegedly connected to Çetin Gören, a figure previously tried in Turkey’s high-profile Bataklık (Swamp) operation. That case was announced in June 2020 by then-interior minister Süleyman Soylu as the “largest drug operation in the history of the Turkish Republic,” with authorities saying 67 suspects were detained and tens of millions of lira seized.

Despite those claims the Bataklık case ended in May 2024 with the acquittal of all 73 defendants. The Ankara 33rd High Criminal Court ruled that prosecutors had failed to prove that seized assets were directly derived from specific drug offenses, a legal requirement under Turkish law. The court held that unexplained or undocumented wealth alone could not be treated as proceeds of a crime.

Company registry documents of the seized vessel’s owners. Although the owners recently stated that the ship had been sold, they were not spared from detention:

Gören, described by prosecutors as the organizer of an international drug network, spent more than two years in pretrial detention before being released. He was later acquitted along with all other defendants. Court records show that Gören had been convicted abroad: A Dutch court sentenced him in 2016 to 12 years in prison for drug trafficking and money laundering linked to a multi-ton cocaine shipment intercepted in Antwerp in 2012; and a Brazilian court sentenced him in 2012 to more than 12 years in prison on drug trafficking charges. Turkish judges, however, concluded that those foreign convictions did not establish a legally sufficient link between specific crimes and the assets seized in Turkey.

The Bataklık verdict reinforced a pattern seen in other large narcotics cases in Turkey, in which suspects are detained during major police operations, held for extended periods and later released or acquitted due to evidentiary standards that courts say are not met. In its 154-page reasoning, the court stressed that prosecutors must identify the exact predicate crime, time frame and amount of criminal proceeds, and ruled that this threshold had not been met.

Court rulings in the Bataklık case and in similar large-scale narcotics investigations show that Turkey’s money laundering laws require that prosecutors establish a direct and concrete link between seized assets and a specific, proven predicate crime. In practice this high evidentiary threshold has led to repeated acquittals in cases that were initially presented by authorities as historic breakthroughs in the fight against drugs and organized crime.

Bataklık was shaped by state policy at the time it was launched, with senior government officials publicly promoting the operation while judicial outcomes later undercut its stated goals. Despite sweeping rhetoric, the case produced no final convictions for drug trafficking or money laundering, raising questions about the effectiveness of such operations beyond their initial announcement.

The Spanish seizure has also drawn attention to Turkey’s growing role in international drug trafficking routes. According to information cited by Turkish prosecutors and foreign law enforcement agencies, the United S had departed from the port of Mersin, stopped at ports in Libya and Morocco, passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and crossed the Atlantic to Brazil. After docking in Fortaleza and Belém, the vessel allegedly took on cocaine near Suriname before heading back toward Europe.

Nordic Monitor previously documented a rise in cases over the past decade in which Turkish-linked vessels, ports or logistics companies appear in large cocaine seizures destined for European markets. Its reporting points to cooperation between Turkish-based criminal figures and international cartels, including Balkan and Latin American networks, based on court documents and official disclosures.

In several maritime cases shipowners have claimed that vessels were sold shortly before being intercepted, distancing themselves from responsibility. Kamer Shipping said the United S, built in 1975, had been sold in October to another company. Similar explanations were offered in earlier seizures involving aging cargo ships carrying multi-ton drug loads.

The contrast between the scale of the Spanish operation and the outcome of Turkey’s past prosecutions points to a recurring pattern in Turkish drug cases, where suspects are detained during highly publicized crackdowns but later move through the justice system without convictions once their cases reach the courts.

Investigations linked to the United S are continuing in both Spain and Turkey. Spanish authorities are pursuing charges related to international drug trafficking, while Turkish prosecutors say they are examining financial and logistical links connected to the vessel. The case now stands as one of Europe’s largest cocaine seizures and a renewed test of Turkey’s stated commitment to combating international narcotics trafficking.