Levent Kenez/Stockholm

The death of three police officers during a counterterrorism operation against suspected Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) members in western Turkey has exposed deep intelligence and security failures that challenge the government’s longstanding narrative of an effective and sustained campaign against the extremist group.

The operation in Yalova was not a confrontation with an unknown cell or an unforeseen threat. It targeted a location that had already been raided months earlier and individuals who had been repeatedly detained, investigated and released despite extensive extremist activity. The outcome has raised fundamental questions not only about tactical decisions taken on the ground but also about the broader structure of intelligence gathering, threat assessment and judicial follow-through.

Immediately following news of the raid, authorities imposed a broadcasting ban, a clear act of censorship that not only obstructed the public’s right to transparent information but also made it impossible to hold the government accountable for its actions.

Authorities said six members of ISIL were also killed during the raid. Officials have not publicly explained why the operation escalated to that extent, why resistance proved so intense or how security forces failed to anticipate the number of suspects inside the house and their level of preparedness. It has also sparked debate regarding how the militants were able to stockpile such a large amount of ammunition without being detected by security forces.

What has attracted particular attention is that the central suspect, Zafer Umutlu, was already known to law enforcement. He had previously been detained in a raid at the same location and had a criminal record that included multiple charges related to ISIS membership. Despite this, he was released and continued to live openly under his own identity, without apparent restrictions

Umutlu’s social media activity was neither hidden nor ambiguous. He publicly shared ISIS propaganda, calls for violence and messages describing repeated police raids that did not result in detention. These posts remained accessible for months, providing a visible record of radicalization and intent.

According to Turkish media, authorities reviewed the accounts followed by Umutlu on Instagram. During the investigation, one user attracted particular attention, a person who is believed to have been in another city at the time of the Yalova raid. Current findings suggest that the organization may have a broader network than previously assumed,, with officials expected to conduct further investigations.

Taken together, the Yalova case suggests that existing warning signs were not translated into preventive action. The location had previously been searched, the main suspect was known to law enforcement for ISIS-related activities and his extremist content remained publicly visible online, yet these factors did not lead to sustained detention or measures that might have averted the fatal outcome.

In the aftermath of the Yalova raid and the tragic loss of three police officers, public attention also returned to footage from an August convoy in the city where religious extremists displayed their banners. This resurgence of imagery highlights a continued presence of radical elements and raises questions about the effectiveness of local monitoring, signaling that extremist symbolism and mobilization remain visible and provocative despite repeated security operations.

Reports in the Turkish media indicate that the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) had submitted a parliamentary motion on January 31, 2024, to investigate ISIS’s Yalova-centered network. However, the motion was not put on the parliamentary agenda due to votes from the ruling party and its allies.

Harshly criticized Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya previously reported in parliament on December 17, 2025, that security forces had carried out 1,457 operations against ISIS in the past 10 months, while persistent failures in intelligence and prevention remain unaddressed. Government statements and social media posts have consistently highlighted raids, arrests and weapons seizures as evidence of sustained pressure on the group. However, the government has not released updated official data since 2020 on how many ISIS suspects are currently imprisoned, prosecuted or released under judicial supervision. Legal experts say this lack of transparency makes it difficult to evaluate whether frequent operations translate into lasting security outcomes or long-term disruption of extremist networks.

The Yalova case illustrates a recurring pattern: ISIS suspects are briefly detained and quickly released, enabling networks to regroup. The system appears busy with operations but fails strategically, prioritizing short-term interventions over sustained disruption.

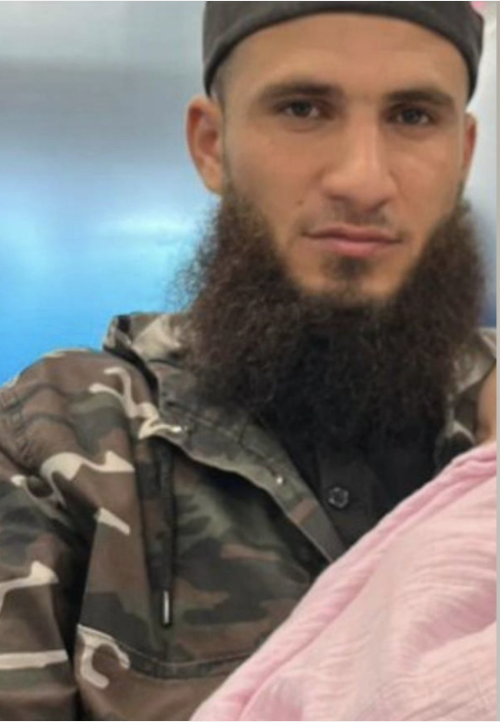

Another ISIS militant killed in the Yalova clash was Haşem Sordabak. Official records indicate that Sordabak was born on March 10, 1997, in Güroymak, Bitlis province. He had a criminal record indicating membership in an armed terrorist organization. Sordabak also maintained a social media account under his real name, where he shared content supporting ISIS members detained in Syria and Iraq.

The criticism is reinforced by earlier cases that revealed similar weaknesses. Bitlis province, where several of the Yalova suspects originally came from, has repeatedly surfaced in investigations involving ISIS recruitment and radicalization. Bitlis was also identified as a key location in the extremist networks linked to Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş, the police officer who assassinated Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov in Ankara in 2016.

Subsequent investigations showed that Altıntaş had been radicalized through Islamist circles connected to ISIS-aligned networks operating in and around Bitlis. Despite the gravity of the assassination and its international repercussions, no comprehensive judicial inquiry dismantled those broader networks.

The Yalova raid was not an isolated failure. In September the abduction and murder of a Turkish bus driver by a group linked to ISIS revealed similar weaknesses. The suspects in that case had been previously detained briefly, lived openly in multiple cities and crossed borders without effective interception despite prior scrutiny.

In both cases, critics say the emphasis on operational outcomes masked deeper institutional problems related to intelligence coordination, judicial processes and post-release monitoring.

ISIS’s presence in Turkey has not disappeared but rather has adapted. Small locally based cells continue to operate within known communities, often under intermittent surveillance rather than sustained disruption. The ability of such groups to regroup, relocate and remain active suggests that the threat has evolved rather than being eliminated.