Levent Kenez/Stockholm

A new report compiled by the Netherlands-based human rights group Stichting Justice Square has detailed a pattern of human rights violations in Turkey following a coup attempt on July 15, 2016, as recognized by multiple United Nations bodies between 2017 and 2024.

The 94-page document, titled “Violation Decisions Given by the United Nations After July 15, 2016,” reviews more than 40 rulings by the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the Human Rights Committee and the Committee Against Torture. It concludes that Turkey has repeatedly violated international human rights obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention Against Torture, despite being party to both treaties.

The report, prepared by lawyers based in the Netherlands, organizes the UN decisions chronologically, showing a consistent pattern of arbitrary detention, lack of due process, enforced disappearances and the use of torture.

Most cases involved civilians, journalists, academics and judges accused of membership in the Gülen movement, which the government refers to as the Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETÖ), blamed for the July 15, 2016 coup attempt. The movement, inspired by the late cleric Fethullah Gülen, has long been critical of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. To date, the Turkish government has not provided verifiable evidence linking the movement directly to the failed coup. Actions taken by Erdogan, the chief of general staff and the head of the National Intelligence Organization on the night of the coup have drawn scrutiny from opposition figures, who argue that these events may have been used to justify a sweeping political crackdown.

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, a body of independent experts established by the Human Rights Council, classified Turkey’s post-coup detentions under several categories of arbitrariness. Category I refers to deprivation of liberty without legal basis. Category II involves detention resulting from the exercise of fundamental freedoms such as expression or association. Category III relates to failure to comply with international guarantees of a fair trial. Category IV covers detention based on discrimination for political or other opinions.

In nearly every Turkish case reviewed, the working group found violations in more than one category. The rulings consistently cited breaches of Articles 9 and 14 of the covenant, which guarantees the right to liberty, presumption of innocence and a fair hearing before an independent tribunal.

According to the UN bodies, emergency decrees issued after the coup were used to justify prolonged detention without charge, secret evidence and restricted access to lawyers. In many cases, detainees were denied contact with family members and held under conditions the UN described as “inhuman and degrading.”

The report states that the UN experts identified a recurring denial of basic procedural rights. The working group noted that suspects were often held for weeks without being informed of the charges against them and that trials relied heavily on anonymous witnesses and digital evidence such as alleged use of the ByLock encrypted messaging app. According to numerous European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) judgments, Turkish courts had used ByLock as the sole or decisive evidence to convict thousands of people of terrorist organization membership, without examining individual circumstances or proving intent, reiterating that this approach was incompatible with basic legal standards.

In one decision the working group ruled that Turkish authorities failed to present any lawful basis for detaining a police officer for more than six months, stating that his right to be promptly informed of accusations and to challenge his detention before a court had been violated. Similar reasoning appeared in dozens of subsequent opinions, including those concerning journalists, civil servants and academics.

The Human Rights Committee, which monitors compliance with the covenant, found that Turkey’s Constitutional Court did not provide an effective remedy for detainees. It emphasized that judicial review must be “genuine and prompt,” not a prolonged or formal process without substantive relief. The committee also ruled that detaining individuals without bringing them before a judge for more than 10 days violated the covenant’s requirement of supervision of detention.

The report also discusses several cases addressed by the UN Working Group on the Committee Against Torture in which Turkish nationals were extradited or abducted from foreign countries and returned to Turkey. The committee determined that such transfers violated the international principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits sending a person to a country where they face a real risk of torture.

In cases involving Morocco, Pakistan and Azerbaijan, the UN concluded that those governments, acting at Turkey’s request, were jointly responsible for unlawful detentions and deportations. The working group found that Turkish authorities bore direct responsibility for these acts and called for the immediate release and compensation of the victims.

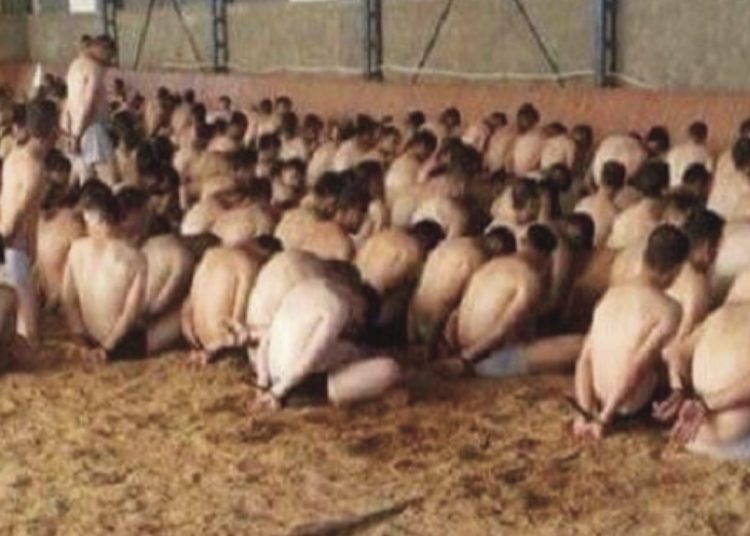

UN experts also documented consistent allegations of torture and ill-treatment in police custody and pretrial detention. The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention referred several Turkish cases to the UN special rapporteur on torture, noting that detainees reported beatings, threats and psychological pressure to obtain confessions.

The UN bodies also expressed concern over the erosion of judicial independence in Turkey. Several rulings involved judges and prosecutors detained on accusations of disloyalty. The working group concluded that these detentions reflected “executive control over the judiciary,” incompatible with the principle of separation of powers required by international law.

The working group found that detentions based on news coverage or alleged sympathy for banned organizations violated the principle of legality, which requires that criminal laws be clear and foreseeable. It warned that vague and overly broad counterterrorism provisions had a “chilling effect” on the press.

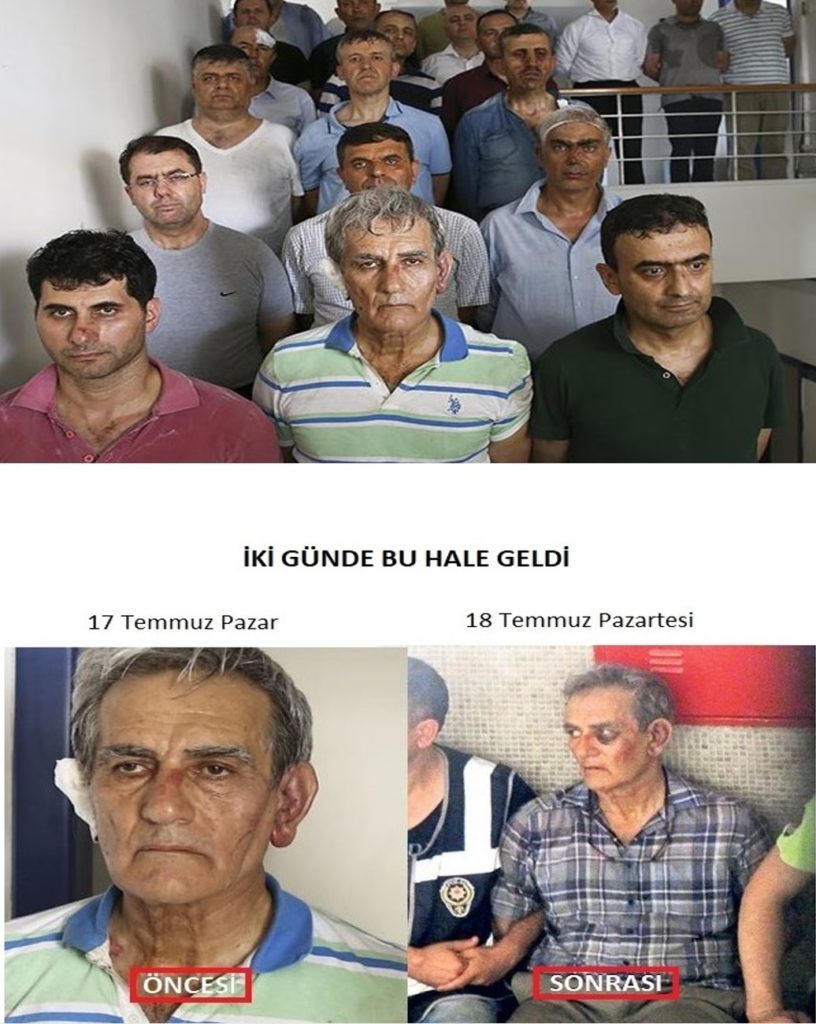

One of the most striking cases cited in the Justice Square report concerns Gen. Akın Öztürk, former commander of the Turkish Air Force, whose detention was recently ruled unlawful by the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. The Turkish government accuses Öztürk of leading the 2016 coup attempt.

In an opinion adopted at its 100th session in August 2024, the working group found that Turkey failed to present credible evidence linking Öztürk to the 2016 coup attempt. The UN body determined that his imprisonment lacked a legal basis and violated international fair trial guarantees under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The decision called for his immediate release, compensation for wrongful detention and an independent investigation into the officials responsible for his treatment.

The opinion described severe mistreatment during his time in custody, including physical abuse, deprivation of food and medical care and denial of access to independent legal counsel. The working group concluded that these acts amounted to torture and that the proceedings against him relied on coerced statements and manipulated evidence.

Once a highly decorated air force commander, Öztürk was sentenced to multiple life terms despite testimony suggesting he had tried to prevent the coup, not lead it. The UN’s findings cast further doubt on the Turkish government’s narrative of the failed coup and add to the growing record of international rulings faulting Ankara for post-coup human rights violations; if even the leader of the coup cannot be directly linked to the attempt, it exposes how hollow the government’s narrative really is

The UN’s rulings, while not legally binding, carry moral and diplomatic weight. Each decision urged Turkey to release detainees, provide compensation and align its laws with international human rights standards.

The findings also have implications beyond Turkey’s borders. The UN bodies stressed that other states must not cooperate in the extraterritorial abduction or deportation of Turkish citizens wanted by Ankara, citing multiple cases in which third countries were found complicit in such violations.

The report concludes that the UN’s findings now form a substantial body of jurisprudence documenting post-coup human rights violations in Turkey. It argues that the consistency of these decisions establishes a pattern that should inform future international accountability mechanisms.