Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

The Islamist government led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has never sought the extradition of fugitives responsible for the deadliest terrorist attack in Turkey’s history, despite knowing their whereabouts in Syria and maintaining close ties with the de facto interim government led by Ahmed al-Sharaa in the war-torn country.

A Nordic Monitor investigation has revealed that although Turkish authorities are fully aware of the locations of several ISIS suspects residing in Syria — and could easily request their detention and handover — not a single formal extradition request has been filed.

These revelations came to light in a letter signed by Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, who previously served as the head of the country’s intelligence agency, MIT.

Fidan’s letter, sent to the speaker of the Turkish Parliament on July 3, confirmed long-standing suspicions: Turkey has shown no genuine intent to prosecute the ISIS fugitives.

The letter, a copy of which was obtained by Nordic Monitor, underscores the Erdogan government’s continued reluctance to confront jihadist groups such as ISIS and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), with the latter led by al-Sharaa, also known by his nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Julan, who once benefited from Turkish intelligence support under Fidan’s leadership.

The case at the center of this scandal involves the twin suicide bombings carried out on October 10, 2015, in the heart of Ankara, killing 104 civilians. The bombings were believed to have been orchestrated by an ISIS cell in Turkey, with strong suspicions of tacit involvement by Turkish intelligence.

The letter by Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan reveals that Turkey never sought the extradition of fugitive ISIS suspects behind the country’s deadliest terror attack:

The timing of the attack —just weeks ahead of the snap parliamentary elections on November 1, 2015 — suggests it may have been used to stoke fear and sway public opinion, ultimately helping Erdogan’s ruling party recover the parliamentary majority it had lost in the June 2015 elections.

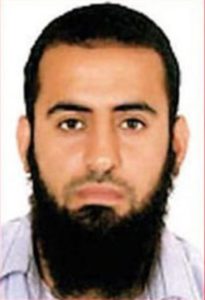

Of the 26 people prosecuted and convicted in the protracted legal proceedings, 16 ISIS operatives — Ahmet Güneş, Bayram Yıldız, Cebrail Kaya, Deniz Büyükçelebi, Edremit Türe, Hasan Hüseyin Uğur, İlhami Balı, Kasım Dere, Kenan Kutval, Muhammet Zana Alkan, Mustafa Delibaşlar, Nusret Yıbnaz, Ömer Deniz Dündar, Savaş Yıldız, Walentina Slobodjanyuk and Yakup Selağzı — remain at large.

While most are believed to be hiding in Syria, some may have fled to Iraq. Court documents, including police intelligence memos, indicate that the locations of at least five fugitives in Syria are precisely known to Turkish authorities. Still, as confirmed by Fidan’s letter, no formal effort has been made to secure their extradition. Instead, the Turkish government relies on INTERPOL Red Notices, without pushing Syria or Iraq for cooperation, an omission that raises serious questions about Ankara’s counterterrorism resolve.

This inaction is less surprising in light of previous revelations. One of the key fugitives, Balı (nom de guerre Abu Bakr or Ebu Bekir) — the mastermind behind three major terrorist attacks in 2015 including an Ankara attack that killed 142 people — had a covert relationship with MIT.

In 2021 Nordic Monitor published a leaked police intelligence memo showing that Balı had been in direct contact with Turkish intelligence officers. The memo revealed that in May 2016, Balı secretly met with MIT agents in Ankara and was put up for three days at the newly opened, five-star Söğütözü Anadolu Hotel, under the protection of MIT officers Serhan Albayrak (a contractor assigned to the Syria desk) and Ahmet Özçelik (a translator on the Iraq desk).

Adding to the scandal, records from Turkey’s National Health System show that Balı underwent three emergency procedures at Cihanbeyli State Hospital in central Turkey on July 25, 2016, while multiple arrest warrants for him were outstanding.

Under Turkish law, police are stationed at state hospitals and health personnel are required to notify authorities if a wanted suspect seeks treatment. What is more, the health system’s digital infrastructure automatically alerts law enforcement when suspects register. Yet, despite all this, no action was taken. Balı walked free.

Observers believe the Erdogan government is concerned that any arrest or trial of Balı could expose the clandestine cooperation between MIT and ISIS, potentially implicating top officials in a scheme that used jihadist networks to advance both domestic and foreign policy objectives.

Wiretaps included in the Ankara bombing case file show that authorities were aware of Balı’s role in facilitating the transit of Turkish and foreign fighters into Syria through Turkey. Nevertheless, no meaningful counterterrorism operations were launched against his network.

Evidence presented during the trial indicated that several deliberate omissions by Turkish authorities may have enabled the 2015 Ankara bombing. The surveillance of the bombers — members of an ISIS cell from Gaziantep near the Syrian border — was mysteriously halted just before the attack. Checkpoints at the city’s entrance were removed, allowing the bombers to drive unimpeded into Ankara.

Following the attack, the Erdogan government imposed a blanket media gag order, blocked a parliamentary initiative to establish an investigative commission, banned public commemorations at the Ankara train station and deployed riot police to disperse grieving families who attempted to hold vigils, often using tear gas and brute force.

Between 2020 and 2025, the court overseeing the case submitted at least six official inquiries to the Ministry of Justice requesting information about the extradition process for the fugitives. Each time, the ministry responded in the negative.

In a final letter dated May 13, 2025, the ministry effectively told the court to stop asking.

“To avoid unnecessary loss of time and effort,” the ministry wrote, “it is considered more appropriate for our ministry to provide information only in the event of developments rather than being asked for updates at regular intervals.” The message made clear that further inquiries about the ISIS fugitives would not be welcome.

Meanwhile, Turkish authorities continue to inflate the number of ISIS-related detentions in public statements, to create an illusion of vigorous counterterrorism efforts. However, convictions remain rare. Most suspects are released after brief interrogations or walk free during trial. When convictions occur, sentences are often lenient.

This reflects the Erdogan government’s permissive — even protective — stance toward ISIS. The judiciary has repeatedly failed to hold ISIS operatives accountable. Even parliamentary attempts to determine how many convicted ISIS members are serving time in Turkish prisons have been blocked by the government, which cites “national security” to justify its refusal to release the data.