Levent Kenez/Stockholm

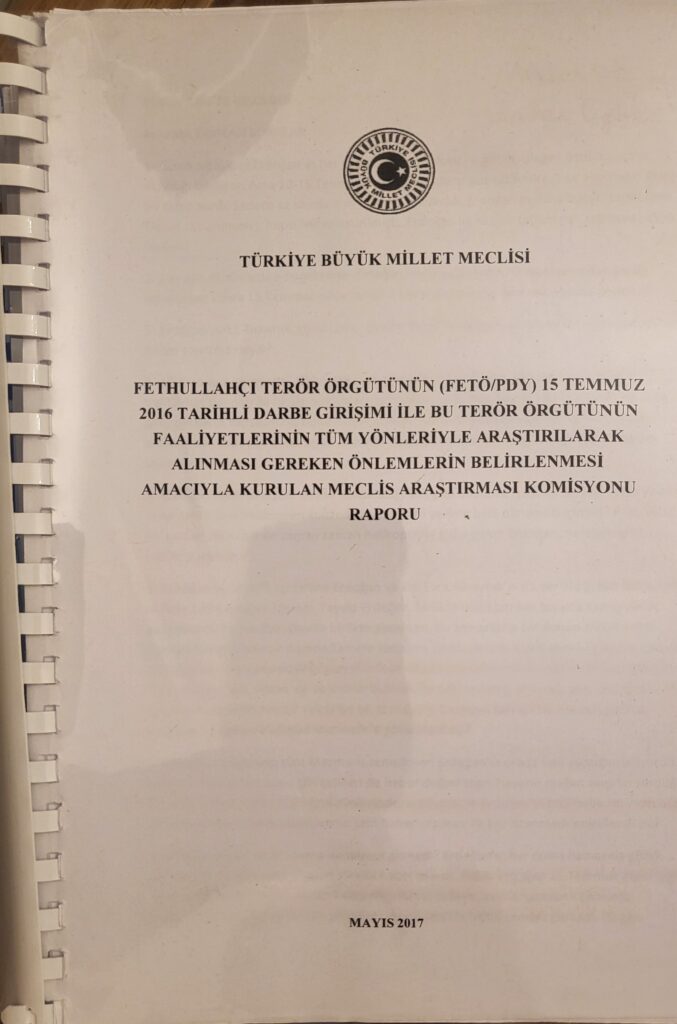

Nine years after a coup attempt in Turkey on July 15, 2016, the most comprehensive parliamentary investigation into the event remains unpublished, a move critics say was driven by fears that its findings could implicate senior government officials and bolster the legal defenses of those accused of involvement, according to behind-the-scenes accounts that have surfaced in recent years.

Although a parliamentary commission was quickly formed to investigate the attempted coup, the final report was never officially released. Despite the passage of nearly a decade, the Turkish Parliament has yet to issue a formal account of the commission’s findings.

The Turkish government has long blamed the abortive putsch on followers of the Gülen movement, which is inspired by the late Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen and has been targeted by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan since the corruption investigations of December 17-25, 2013, which implicated him while he was serving as prime minister, along with his family members and inner circle.

The Erdogan government refers to the movement as a terrorist organization, though its members deny involvement in the coup attempt and claim the attempted takeover was used as a pretext for an extensive purge of dissidents.

The government’s unilateral designation of the group as a terrorist organization has not been formally recognized internationally, a reluctance widely attributed to the belief among global actors that the label is politically motivated rather than based on independently verifiable evidence.

According to accounts shared in the Turkish media, the decision to withhold the parliamentary report was made after senior political figures were warned of the potential legal dangers of releasing it. Just before the report was scheduled for publication in 2017, prominent legal experts are said to have visited top ruling party officials, including parliamentary leaders, and advised against making the findings public.

“They said the facts, allegations and documentation in the report could later backfire on you,” journalist Barış Pehlivan revealed despite his opposition to the Gülen movement during a nationally broadcast television appearance in 2021. “A published parliamentary report could support legal cases abroad and damage Turkey’s position internationally. Their advice was: Don’t officially print the report.”

That behind-the-scenes warning, according to the same broadcast, prompted the shelving of the document despite months of work and extensive hearings. Selçuk Özdağ, the vice chair of the commission, confirmed these claims, stating that the political leadership was indeed cautioned and influenced by legal concerns.

Following the end of İsmail Kahraman’s term as speaker of parliament, it emerged that the final report had not been archived or formally submitted in accordance with parliamentary procedure. His successor, Mustafa Şentop, confirmed that no valid report had been entered into the records of the parliament.

“In line with parliamentary bylaws, a report must be agreed upon by the commission and submitted officially,” Şentop said in a public statement. “There is no report that meets these criteria. Therefore, no official commission report exists on the July 15 events.”

However, documentation and testimony from multiple opposition members of the commission tell a different story. They say a draft was prepared, circulated and even sent to the speaker’s office in July 2017.

The lack of an official archive record, critics argue, is a deliberate maneuver designed to erase the report from institutional memory and avoid public scrutiny.

The commission held 22 meetings for a total of 142 hours, during which it heard testimony from representatives of 94 institutions and 50 individuals. Members also conducted on-site inspections at key locations, including the Grand Yazıcı Hotel in Marmaris, where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was initially reported to have narrowly escaped capture, a claim that was later contested, and the Bosporus Bridge in Istanbul, where dozens were killed during clashes.

Over the course of its work, the parliamentary commission generated multiple iterations of its findings. The first version, a 936-page draft, was leaked to the press in December 2016, revealing extensive testimony and preliminary assessments. Months later, in May 2017, a revised 639-page draft was circulated internally to gather dissenting views from minority members of the commission. What was believed to be the final version, comprising 1,097 pages, was reportedly delivered to the Office of the Speaker on July 12, 2017, just days before the commission’s mandate expired.

According to the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), the first version contained serious investigative material and reflected a genuine effort to uncover the truth. The second, shorter version removed significant content, raising suspicions of political interference. The final version, the CHP claims, included politically motivated accusations and excluded dissenting opinions submitted by opposition members.

Excerpt from the opposition dissent note submitted by the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) on the coup investigation report:

One controversial section added in the final version accused then-CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu of having close ties to the network blamed for the coup, an assertion denied by the party and never proven in court.

“The government’s aim was never to investigate the coup,” a CHP document said. “The goal was to weaponize the narrative and silence critics.”

Notably, two of the most central figures of the July 15 events, then-chief of general staff Hulusi Akar and then-National Intelligence Organization (MİT) director Hakan Fidan, were not called to testify before the commission. This omission, despite repeated opposition requests, has been one of the main sources of controversy.

Observers believe their testimony could have shed light on early warnings, response strategies and potentially conflicting accounts of what unfolded that night. Their absence has led many to question the credibility and completeness of the commission’s work.

The official account states that only 8,651 military members took part in the coup, corresponding to 1.5 percent of the Turkish Armed Forces. Of those, 1,761 were conscripts and 1,214 were military cadets. Given that some 150 generals and thousands of lower-ranking officers were sentenced on coup charges, military experts find it odd that such a small number of troops allegedly participated. Many believe it was a false-flag operation Erdogan used to purge his opponents within the military and consolidate power.

By branding the coup as a wide-ranging conspiracy, the government justified mass arrests, constitutional amendments and the imposition of a two-year state of emergency. Critics say this period marked the beginning of a new era of authoritarian rule in Turkey, characterized by the erosion of judicial independence, freedom of expression and political pluralism.

Notes from the first meeting of the parliamentary commission:

Opposition parties were not silent during the commission’s investigation. The pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) in its official note declared that the commission’s final output “did not aim to shed light on the coup but rather to legitimize the government’s version of events.”

“The final report fell far short of answering pressing questions,” the party said in its note. “The commission bent the facts to reinforce a single political thesis. The declared state of emergency has since institutionalized a level of lawlessness that resembles the very coup it claimed to resist.”

The HDP noted that, rather than promoting reconciliation and clarity, the government’s response deepened social divisions and fostered an atmosphere of fear and suppression.

Despite repeated calls from lawmakers, journalists and civil society, the July 15 commission report remains buried, if not entirely erased. Parliament has refused to revisit the issue, and no serious attempt has been made to republish or investigate the report’s findings.

Meanwhile, according to data published by the state-run Anadolu news agency on July 14, 2025, a total of 390,354 individuals have been detained in post-coup investigations as of July 2025. Of these, 113,837 have been arrested on suspicion of participating in the uprising or belonging to banned organizations.