Abdullah Bozkurt / Stockholm

The assassination of a 48-year-old drug trafficker in Turkey has cast a revealing spotlight on how Iranian criminal figures are able to effortlessly obtain Turkish citizenship, adopt new identities and orchestrate expansive transnational criminal operations — often with minimal resistance from, and in some instances with the direct facilitation of, Turkish authorities.

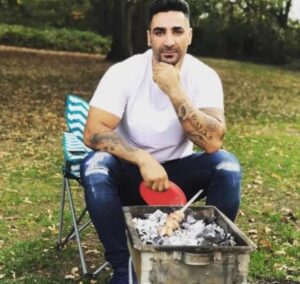

The revelation emerged following the fatal shooting of Iranian national Yousef Ali Akbari in Istanbul on the evening of December 8, 2024, in what appears to have been a turf war between rival criminal networks. While Turkish authorities launched an investigation — standard protocol in the aftermath of such incidents — the case inadvertently exposed troubling details about how Akbari and his associates had been operating with near-total impunity in Turkey.

According to the investigation, Akbari acquired Turkish citizenship in 2023 and officially adopted the Turkish name Aras Yılmaz in an effort to conceal his true identity, despite a well-documented criminal history. He had two prior entries in police records and had already been flagged by both Turkish law enforcement and the National Intelligence Organization (Millî İstihbarat Teşkilatı, MIT) for his involvement in illicit activities.

How Akbari managed to pass the citizenship vetting process remains unclear, as the investigation file contains no information regarding how he obtained approval or who may have facilitated it. Under normal procedures, multiple red flags should have been triggered during the review of his application. His successful navigation of these safeguards strongly suggests the involvement of high-level protection within the Turkish government or assistance from individuals wielding considerable political influence.

All applications for Turkish citizenship ultimately require approval from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has significantly eased the process for foreigners investing in Turkey or purchasing property. With the judiciary and law enforcement institutions firmly under the Erdogan government’s control, legal issues faced by international fugitives can often be resolved through bribes, political protection or direct intervention.

Further investigation into Akbari’s murder revealed that another Iranian associate in his network, who also obtained Turkish citizenship and assumed the name Sait Aksoy, had similarly been naturalized.

Akbari is believed to have established a criminal enterprise in Turkey under the apparent protection of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP), a key political ally of President Erdogan. The MHP has long faced allegations of serving as a political patron for mafia networks, organized crime syndicates and drug trafficking operations. Both the party and Erdogan are benefiting financially through kickbacks and bribes in exchange for providing legal cover and administrative immunity to these groups.

Akbari played a central role in trafficking drugs from Iran to Turkey, with subsequent distribution to third countries. He was also involved in sourcing raw materials from Iran to manufacture narcotics in clandestine laboratories set up in Turkey. Among his known associates was Reza Hamati, an Iranian national and a pivotal figure in the network.

Prior to his assassination near a restaurant at the Vadi Istanbul shopping mall in the Ayazağa district of Sarıyer, Akbari had operated with minimal interference from Turkish authorities. It was only following his death that a limited crackdown was initiated. Three weeks later, police arrested eight suspects — both Turkish and Iranian nationals — in what appeared to be a “controlled and limited” operation, seemingly designed to provide the government with a pretext for plausible deniability. Those arrested included İsmail Gözde, Meysam Zohouri Rad, Milad Sadeghzadeh, Hemati, Ahmet Khaleel, Sait Aksoy, Burak Uşar and Berat Ayhan.

The investigation appears to have been strategically managed to mitigate the political fallout from Akbari’s murder. While minor operatives were apprehended, the central figures orchestrating the drug trafficking network, along with those offering political and legal protection, were left untouched by Turkish law enforcement.

Case files reveal that Akbari’s top aides, Hamati and Mahmoud Davarpanah Fard — both Iranian nationals — were well known to Turkish authorities, who were fully aware of their networks, operational methods and Turkish associates. In rare instances, police and customs officials successfully intercepted shipments, seizing over four tons of methamphetamine, 70 kilograms of heroin and 105 kilograms of precursor chemicals used in drug production.

For instance, one significant seizure — 1,982 kilograms of liquid methamphetamine in the border province of Ağrı on March 14, 2024 — was directly linked to Akbari’s network. Despite this, no action was taken against him or his top associates at the time, and the investigation file provides no explanation for this apparent inaction.

Facing criticism for their delayed response, Turkish authorities scrambled to assert that an investigation into the network had been launched as early as September 2022, leading to some arrests and seizures. However, no convincing explanation was offered for their failure to target Akbari or his senior operatives, with authorities instead focusing on low-level street dealers.

Wiretaps included in the investigation file reveal that the drug operation persisted even after Akbari’s murder. His deputies were recorded discussing shipments of ethanol — a crucial precursor in methamphetamine production — being transported from Iran to Turkey, frequently clearing customs without incident. The network also brought in Iranian chemists and specialists to assist with drug manufacturing, yet none of those people were apprehended by Turkish authorities.

Akbari was ultimately murdered as a result of an internal dispute within the drug network. He was shot by contract killer Mert Akçay, who was paid 1 million Turkish lira for the job and received his orders from rival trafficker Emre Battal, whose business had been undermined by Akbari’s expanding operations. Battal remains at large.

Akbari’s case is not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern in Erdogan’s Turkey, where Iranian criminal figures including those affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force have found a safe haven to carry out illegal activities.

Another Iranian national, Ahmed Nazari Shirehjini, who is wanted in Europe on organized crime charges, was recently identified as yet another criminal who obtained Turkish citizenship. Like many others involved in the drug trade and organized crime, Shirehjini has ties to Mehmet Ağar, a former interior minister believed to control significant portions of Turkey’s police apparatus.

In fact, trade records reviewed by Nordic Monitor reveal that Shirehjini is listed as a business partner of Ağar’s son, Zülfü Tolga Ağar, a lawmaker from Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and a member of the parliamentary Defense Committee.

Ağar — long considered a mafia godfather in Turkey — maintains close ties to various organized crime syndicates and operates with impunity, thanks to the political protection he enjoys from both the AKP and its partner, the far-right MHP.

Shirehjini, who is currently outside Turkey, has also been linked to drug trafficking and illegal gambling operations in the Turkish-controlled breakaway territory of northern Cyprus. He has reportedly laundered money on behalf of the Iranian regime through various illicit schemes.

Over the past decade, the US government has imposed sanctions on numerous Turkish individuals and entities for facilitating Iranian sanctions evasion, reflecting the permissive environment provided by the Erdogan administration. Corruption investigations in Turkey in 2013 — and subsequent US federal court cases — further exposed Erdogan’s ties to Reza Zarrab, an Iranian sanctions-buster who laundered billions of dollars through Turkish banks on behalf of Tehran.