Abdullah Bozkurt / Stockholm

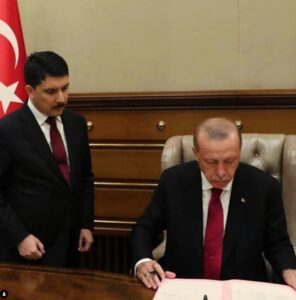

Hasan Doğan, chief of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s cabinet — the Turkish equivalent of the American chief of staff — occupies one of the most influential and strategic positions in the Turkish government. He acts as the gatekeeper to the highest office in the land and serves as the behind-the-scenes whisperer shaping presidential decisions and national policies.

A theology graduate, Doğan began his political journey in the now-defunct Felicity Party (Fazilet Partisi), a pro-Iranian Islamist group rooted in a Turkish interpretation of the Muslim Brotherhood ideology. After the Constitutional Court banned the party in June 2001 over alleged fundamentalist activities, Doğan aligned himself with Erdogan’s newly formed Justice and Development Party (AKP), established just two months later.

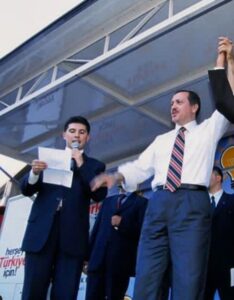

Doğan started out in the AKP’s youth branches, often serving as Erdogan’s warm-up speaker during election rallies. Over time, he became one of Erdogan’s most trusted aides. He was deputy chief of staff when Erdogan was prime minister, and by 2008, he had risen to the role of chief of staff — a position he has held ever since, even after Erdogan transitioned to the presidency in 2014.

Although officially awarded the symbolic title of ambassador, the real influence Doğan wields far surpasses the status of any cabinet minister or vice president. He can exert his will on any government agency with minimal resistance, due to the power he holds as Erdogan’s closest confidant and gatekeeper.

Doğan controls access to the president, influences senior appointments in the administration, and filters the information that reaches Erdogan’s eyes and ears. Perhaps no one understands Erdogan better than his chief of staff, who works him day and night and follows him closely like a shadow. Doğan is deeply familiar with Erdogan’s impulses, instincts and private sentiments toward both allies and enemies. He knows exactly which emotional buttons to push to steer the president in a desired direction.

This makes him uniquely positioned to manipulate Erdogan’s decisions. For instance, Doğan is well aware of Erdogan’s aversion to individuals who receive glowing media attention. The president is notoriously suspicious of anyone who gains popularity through the press, fearing that factions within the government are attempting to “sell” candidates to him via media coverage.

Doğan exploits this by feeding strategic information to pro-government media outlets, crafting narratives that influence Erdogan’s opinion on candidates for cabinet posts or other high-level appointments. In many cases, Erdogan ends up choosing the individual Doğan prefers, possibly without even realizing the manipulation.

Born into a poor family in Kızılcahamam, a district in Ankara Province, Doğan has nonetheless amassed a personal fortune. Much of it reportedly comes from illegal commissions earned by selling access to the president. According to insiders, even arranging a meeting with Doğan himself can cost lobbyists and businesspeople over $100,000 — a price paid by those seeking government contracts, licenses or favors.

A lifelong hardline Islamist, Doğan has long been the go-to figure for radical groups seeking access to the presidency. Confidential documents previously published by Nordic Monitor included wiretaps that captured Doğan in private conversations with known Islamists, during which he offered help for their causes.

One such individual was Yasin al-Qadi, an Egyptian-born Saudi national who had been blacklisted by both the US Treasury and the United Nations al-Qaeda Sanctions Committee. In 2013, al-Qadi sought Doğan’s help in securing a Schengen visa after failing to obtain one independently. Doğan lobbied several Western embassies in Ankara using the influence of the presidency. While most embassies declined the request, the Finnish Embassy considered it, though their decision was delayed pending instructions from Helsinki.

At the time, al-Qadi was transferring large sums of money to Turkey as part of a joint business venture with one of Erdogan’s sons, Necmeddin Bilal Erdogan. Turkish investigators described this venture as an organized crime operation aimed at defrauding the state of valuable public property in Istanbul. Despite being under a UN travel ban, al-Qadi was frequently meeting with Erdogan and then-intelligence chief Hakan Fidan.

When the visa plan failed, Doğan advised al-Qadi to obtain Turkish citizenship to ease his international travel.

In another case, Doğan received an urgent request in September 2013 from Osama Qotb, nephew of Sayyid Qutb — the ideological father of the Muslim Brotherhood. Qotb asked Doğan to intervene on behalf of radical Kuwaiti cleric Sheikh Hakim al-Mutairi, a convicted felon with known ties to al-Qaeda. Al-Mutairi had been barred from entering Turkey, but following pressure from Erdogan’s office, he was allowed entry.

Later, when al-Mutairi was scheduled to participate in an anti-Egypt conference in Istanbul, Turkish authorities initially shut it down. However, after Qotb reached out to Doğan, the event was allowed to proceed. Al-Mutairi was even granted Turkish residency. In December 2023, he was briefly detained on a Kuwaiti arrest warrant but was quickly released following intervention at the highest levels of Erdogan’s administration.

Doğan is now reportedly working with Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan, a former spymaster, to position Fidan as Erdogan’s successor in the event of the president’s death or health-related departure from office. Doğan believes that by helping Fidan rise, he can retain — or even expand — his power in a post-Erdogan era.

The influence that comes with Doğan’s title is immense. He plants loyalists in key positions across the bureaucracy, controls Erdogan’s agenda and schedule and even fills the president’s calendar to distract him while pushing other bureaucratic maneuvers behind the scenes.

As Erdogan’s gatekeeper, Doğan holds more sway than any official in the ruling party or government. Ministers sometimes wait weeks or even months to meet with Erdogan — delays often orchestrated by Doğan as a demonstration of his own power.

Occupying a critical intersection in Turkey’s bureaucratic machinery, Doğan can either expedite or delay official processes. For example, he can forward documents needing the president’s signature or let them sit on his desk indefinitely. From appointing local health directors to naming university rectors, most mid and high-level appointments require Erdogan’s approval — which in practice means they go through Doğan first. Hundreds of documents reach the presidency each week requiring the president’s signature, and Erdoğan relies heavily on Doğan, often signing them without bothering to review their contents.

Rarely making public statements, Doğan prefers to operate from the shadows, using proxies to exert his influence. Yet he holds the key to the most powerful office in Turkey, quietly shaping both policy and the future of the nation — especially as he works behind the scenes on Erdogan’s succession plan.