Levent Kenez/Stockholm

The Turkish Parliament approved a controversial cybersecurity law on March 12, amending certain provisions but retaining penalties for spreading “false information” about data leaks, a clause critics say threatens press freedom and free speech.

The law, which aims to bolster Turkey’s cyber defenses, establishes a legal framework for the recently formed Cybersecurity Directorate. It grants the directorate broad authority over data collection and cybersecurity enforcement, raising concerns among civil rights groups about potential overreach and privacy violations. The law is part of Turkey’s broader effort to modernize its digital infrastructure amid rising cyber threats targeting government agencies, financial institutions and private enterprises.

One of the most contentious provisions — allowing the Cybersecurity Directorate to conduct searches and seize data without a court order — was removed from the final version of the bill following strong opposition from lawmakers and civil rights groups. However, Article 16, which imposes criminal penalties for disseminating false information about cyber incidents, remains a focal point of criticism.

Text of the new cybersecuty law:

Under an amendment proposed by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), Article 16’s revised fifth clause states: “Anyone who, despite knowing there is no data breach in cyberspace, creates or disseminates false content to incite public concern, fear or panic, or to target institutions or individuals, shall be sentenced to two to five years in prison.”

Opponents argue that the clause’s vague wording could be used to suppress investigative journalism and silence whistleblowers. Media watchdogs and human rights organizations warn that journalists reporting on cybersecurity breaches could face prosecution, even when covering legitimate concerns about data protection. Critics state that similar provisions in Turkey’s disinformation law have led to the prosecution of journalists and social media users in the past, raising fears that the new cybersecurity law could further erode press freedoms.

The legislation calls for harsh punishment for cyberattacks against Turkey’s critical cyber infrastructure. Individuals involved in cyberattacks or in storing unlawfully obtained data in cyberspace now face between eight and 12 years in prison. Additionally, those who obstruct cybersecurity authorities from accessing requested documents, software or data could receive one to three years in prison and a fine.

Furthermore, the law criminalizes breaches of confidentiality obligations and abuse of authority, imposing sentences ranging from four to eight years for violations. Cybersecurity experts warn that while stricter penalties may deter cybercriminals, the law’s broad definitions could also be used against individuals who inadvertently possess or share sensitive digital content.

As Turkey seeks to strengthen its digital infrastructure, cyberattacks have increased in both frequency and sophistication. In 2023 Turkey faced multiple large-scale cyberattacks targeting financial institutions, telecommunications networks and government platforms. According to the Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK), Turkey has recorded a 40 percent increase in cybersecurity incidents over the past two years. These attacks have underscored the need for a robust legal framework, but critics argue that the new law prioritizes state control over digital security rather than protecting individual privacy.

Nordic Monitor previously reported that the Cybersecurity Directorate was given extensive powers under the new law, raising concerns over potential surveillance and privacy violations. The law formally defines the responsibilities of the Cybersecurity Directorate, established by presidential decree on January 8. The directorate will oversee cybersecurity resilience and maturity levels for public institutions and critical infrastructure organizations. It will also conduct risk assessments, maintain data inventories and implement cybersecurity measures.

A cybersecurity council, to be chaired by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, will be established to shape national cybersecurity policy and strategy. The council will include ministers, the head of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MİT), the Defense Industry Agency president and the Cybersecurity Directorate chief. Critics argue that the council’s composition heavily favors government and security agencies, limiting independent oversight.

Additionally, the Cybersecurity Directorate is empowered to conduct cyber threat intelligence gathering, analyze malware and cooperate with international cybersecurity agencies. However, concerns remain over how Turkey will handle cross-border data sharing. Article 6 of the law grants the directorate the ability to share cybersecurity-related data with foreign entities, but it lacks explicit safeguards against potential misuse by foreign governments or corporations. Critics warn that without a strong data protection framework, sensitive national security information could be exposed to external threats.

Despite the amendments, civil rights groups remain concerned about the law’s potential impact on freedoms. Journalists and activists argue that the law’s broad and vague definitions — such as “critical infrastructure” and “cyber threats” — could lead to arbitrary enforcement.

The Freedom of Expression Association has warned that the law lacks sufficient judicial oversight, undermines the principle of legal certainty and grants excessive powers to the executive branch without adequate checks and balances. The group urged lawmakers to introduce additional safeguards to prevent abuse.

Legal experts have pointed out that the law’s provisions conflict with international human rights standards. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has previously ruled against Turkey in cases involving restrictions on freedom of expression and digital rights. If the law is enforced in a way that suppresses dissent or investigative journalism, it could result in new legal challenges at the international level.

The law comes amid growing concerns over data security in Turkey following multiple high-profile data breaches. Reports indicate that personal information from government databases has been illicitly sold online, with opposition lawmakers citing documented cases of compromised data, including leaks from the Supreme Election Council (YSK) and the Ministry of Health. These incidents have fueled public skepticism over whether the government can effectively safeguard citizens’ data while increasing state control over digital spaces.

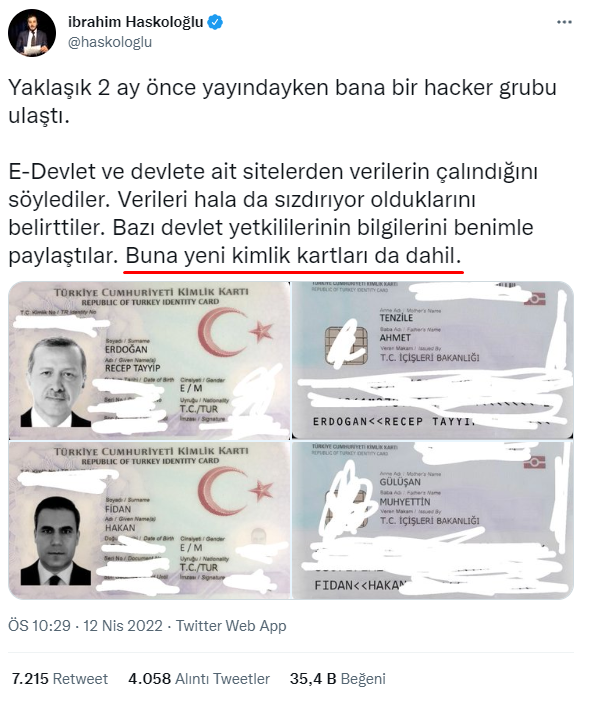

Public anxiety over cybersecurity escalated in 2022, when journalist İbrahim Haskoloğlu shared identity documents allegedly belonging to President Erdogan and former intelligence chief Hakan Fidan. Haskoloğlu claimed that a hacker group had accessed Turkey’s state-run E-Devlet system, exposing systemic vulnerabilities. While his revelations prompted discussions on cybersecurity deficiencies, Haskoloğlu was arrested and detained for eight days before being released pending trial.

In recent years Turkey has faced increasing scrutiny over its digital policies. In 2020 the government passed a social media law requiring platforms like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube to appoint local representatives and comply with government takedown requests. The law led to increased censorship, with thousands of social media posts removed or restricted. Critics fear that the cybersecurity law could be used in a similar manner to control online discourse and limit public access to information.