Levent Kenez/Stockholm

A former military officer and Turkish intelligence operative convicted of smuggling arms to jihadist groups in Syria claimed in court on January 2 that he once had close ties with the leader of Syria’s Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a militant group that evolved from al-Qaeda’s former affiliate and ousted President Bashar al-Assad on December 8.

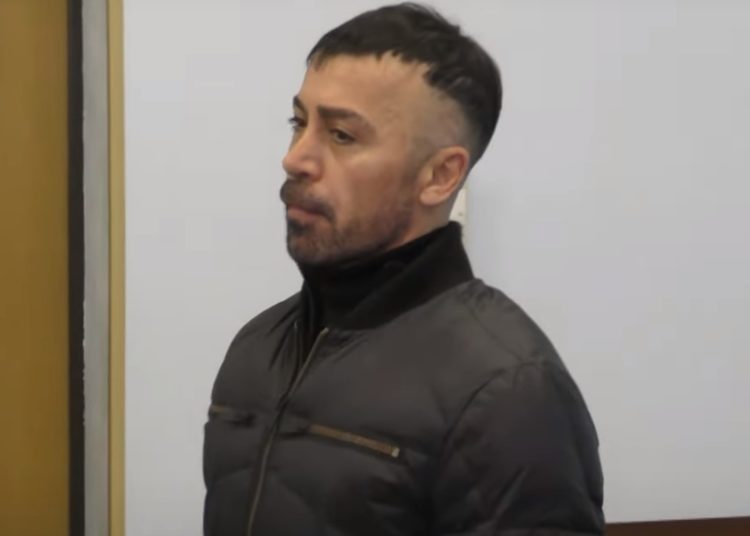

“I was friends with Syria’s Ahmed al-Sharaa, also known as al-Jolani. Now Jolani is in power, and I’m the one serving a sentence for selling weapons to them,” said Nuri Gökhan Bozkır in his defense, Turkish media reported.

Bozkır, who had previously been released in the high-profile trial concerning the 2002 murder of academic Necip Hablemitoğlu, was later sentenced to more than 21 years in prison for trafficking arms and explosives disguised as onion shipments to Syria. Despite his lengthy sentence, he was surprisingly released on probation but was rearrested for violating judicial supervision measures.

During the last hearing, he expressed frustration with what he described as a betrayal by the state, saying, “The work I did for my country’s interests has turned into a legal case against me.”

Nordic Monitor had previously compiled reports detailing Bozkır’s court statements and profiling his complex background, shedding light on his role in covert operations and shadowy dealings. Bozkır is a former Turkish military officer and arms smuggler whose story is marked by allegations of clandestine operations, illegal extraditions and controversial ties to both Turkish and Ukrainian intelligence. Born into a life that initially revolved around military discipline, Bozkır’s trajectory took a drastic turn following his dismissal from the Turkish Armed Forces. Accused of engaging in illicit arms trafficking, he became embroiled in international controversies, particularly regarding the Syrian conflict and the clandestine world of intelligence operations.

Bozkır fled Turkey in 2015 in the midst of a criminal investigation into his alleged role in supplying arms to jihadist groups in Syria, reportedly in coordination with Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization (MIT). His departure for Ukraine marked the beginning of a prolonged saga involving legal battles, accusations of political maneuvering and claims of abuse. Despite living in Ukraine in relative safety, his alleged crimes continued to attract the attention of Turkish authorities. The turning point came in January 2022, when Ukrainian intelligence operatives handed Bozkır over to Turkish intelligence in a covert operation. The method of his transfer — reportedly in a coffin aboard a Ukrainian aircraft — highlighted the secretive and extrajudicial nature of the operation.

Following his arrival in Turkey, Bozkır claimed he was subjected to 25 days of torture at a black site run by MİT near Ankara’s Esenboğa Airport. He described being confined in a small box, beaten and forced to endure physically and psychologically abusive conditions. He alleged that his captors injected him with unknown substances, rendering him semi-conscious for days. His claims of torture were dismissed by Turkish authorities, who presented his detention as a legal process. Despite his appeals for an investigation into the alleged mistreatment, the judicial system appeared to shield the intelligence agency from scrutiny, with the presiding judge reportedly aligned with the government’s political agenda.

Bozkır had confessed in previous hearings that in 2019, due to an embargo, he supplied arms and ammunition that the Turkish military was unable to procure to jihadist groups in Syria:

Bozkır’s name is also tied to one of Turkey’s most infamous unsolved murders: the 2002 assassination of academic Necip Hablemitoğlu. Turkish prosecutors accused Bozkır of involvement in the killing, alleging that the operation was carried out by a military unit to which he belonged. However, Bozkır insists he was scapegoated by the administration of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan as part of a broader strategy to eliminate political opponents and consolidate power.

He also helped the Erdogan government in a witch hunt pursued against members of the Gülen movement, a group that is opposed to Erdogan and critical of his regime for pervasive corruption and Turkey’s aiding and abetting of armed jihadist groups. He said he had informed Turkish authorities about members of the Turkish Armed Forces who he claimed had links to the movement so they could be purged.

His personal life in Ukraine, where he lived with his Ukrainian wife and maintained a network of business interests, added another layer of complexity to his story. He claimed to have connections to high-ranking Ukrainian officials, including former and current presidents, and even offered to assist Turkish intelligence in tracking down dissidents in Ukraine.

In previous court hearings, Bozkır admitted to acting as a subcontractor for companies having contracts with Turkey’s top defense procurement institution, the Defense Industry Agency (Savunma Sanayii Başkanlığı, SSB).

“In 2019, during the Afrin operations, there was a covert embargo on Turkey, making it difficult to procure critical ammunition. The Free Syrian Army [FSA] wasn’t receiving supplies,” Bozkır testified. “I had stockpiles in my warehouses in Ukraine and was supplying them. I operated as a subcontractor for companies contracted by the SSB,” he said.

The reopening of the Hablemitoğlu murder case, in which Bozkır stands accused, carries significant political ramifications in Turkey. It highlights the delicate balance between President Erdogan’s government and the neo-nationalist factions, once considered adversaries. Observers suggest that Erdogan has used the case strategically to eliminate rivals and tighten his control over key state institutions. The involvement of influential figures, such as billionaire İnan Kıraç and senior military officials, indicates that Bozkır’s story is closely linked to the broader power struggles within Turkey’s political and intelligence networks.

By revisiting past cases and exposing the illegal activities of these nationalist elements, Erdogan appeared to deliver a calculated warning to deter dissent within these circles.