Levent Kenez/Stockholm

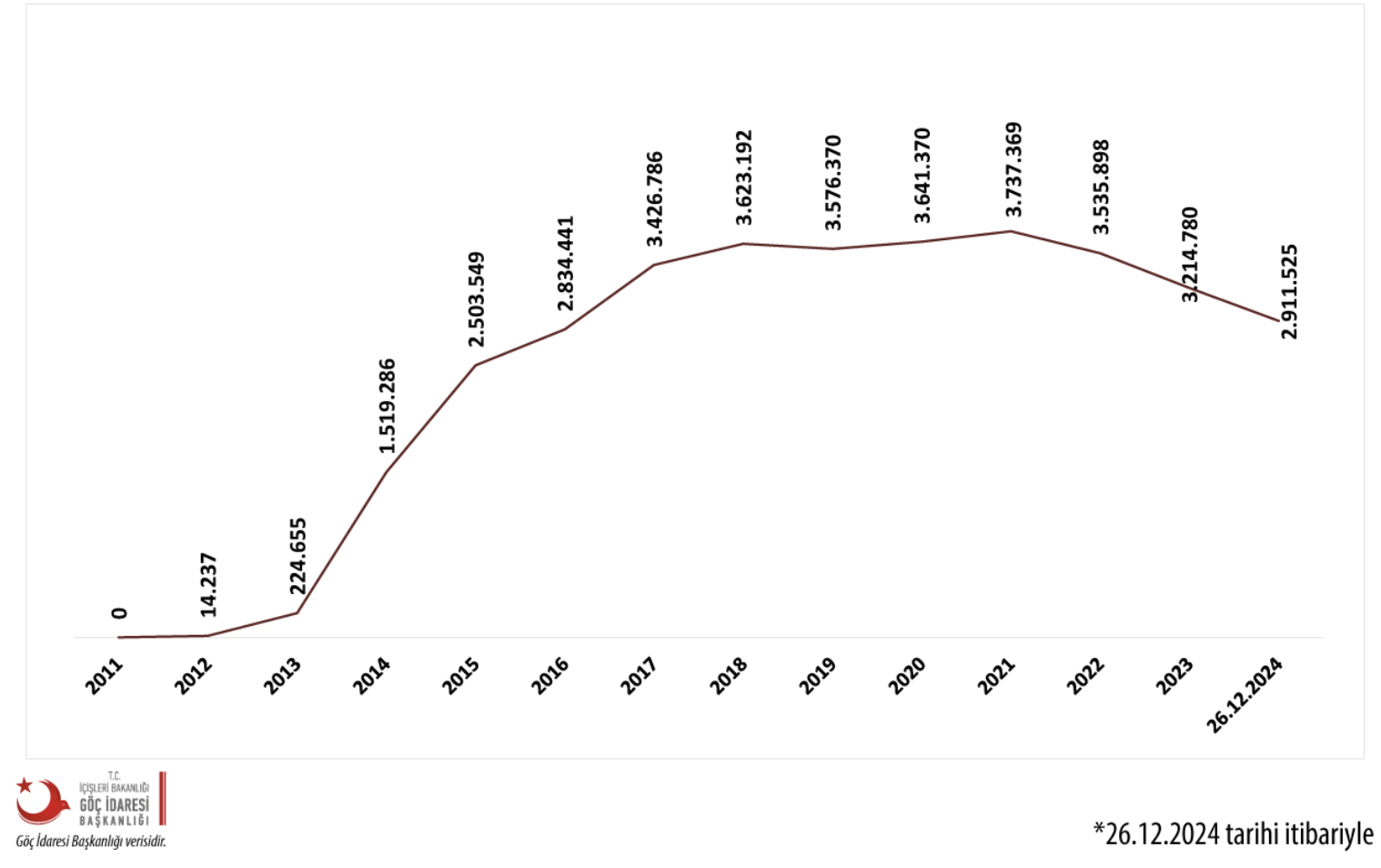

Following the December 8 takeover of Damascus by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a coalition of Islamist groups supported by Turkey and dominant in Syria’s opposition-held regions, former President Bashar al-Assad was ousted, signaling a dramatic shift in Syria’s political landscape. In the aftermath of this development, the future of the 2.9 million Syrians under temporary protection status in Turkey, according to official figures, became one of the country’s most pressing issues. While the opposition calls for the return home of all Syrians, the government does not share the same view. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has made clear that no one will be forced to return, saying that Syrians who want to stay in Turkey can do so. However, in a country where public unease about refugees is growing, Erdogan’s stance is underpinned by political, diplomatic and economic considerations.

Speaking at his ruling party’s meeting in parliament on December 25, Erdogan said, “We are providing every possible kind of assistance to our Syrian brothers and sisters in Turkey who want to return, either temporarily or permanently. We will also allow for temporary border crossings for a certain period of time. By summer, with schools going on holiday, we expect increased activity at border gates, and we are already making preparations for this.”

He went on to say, “Our policy will be as follows: We will assist those who want to return, but we will not force anyone to leave. For our brothers and sisters contributing to Turkey’s economic, academic, scientific or commercial life, we will keep our doors open if they want to stay,” adding, “As always, the opposition will undoubtedly try to undermine this process as they have in the past.”

The main reasons behind Erdogan’s allowing Syrian refugees to stay in Turkey lie primarily in the demands of the small and medium-size business sector that supports him. Turkey’s large Syrian refugee population plays a significant role in the country’s labor market. The Turkish government and businesses are keen on maintaining this labor force, despite ongoing debates over their return to Syria. Syrians, especially those working informally, contribute to filling labor gaps in areas where local Turkish workers are reluctant to take jobs, primarily in agriculture, construction and low-wage factory work. This includes crucial areas such as livestock breeding, where labor shortages are widely reported. For instance, Turkish officials have acknowledged the difficulty in finding workers for tasks such as shepherding, an area where Syrians provide much-needed manpower. This reliance on Syrian workers, often willing to accept lower wages and harsher working conditions, has made them indispensable for sectors that are integral to the Turkish economy.

According to the Ministry of Labor and Social Security’s Foreign Work Permit Statistics for 2023, 108,520 Syrians in Turkey have work permits. However, a significant portion of Syrians are believed to be working informally. It is estimated that around 1 million Syrians are employed in total. To work legally, Syrians must have a work permit, which can only be applied for by their employers, who are also required to pay a work permit fee. After hiring, employers must provide at least the minimum wage to the workers. Furthermore, there is a specific employment quota for Syrians in certain sectors. If a Syrian worker is granted a work permit, it is valid only in the province where their temporary protection status is recognized.

Experts suggest that the Turkish government turns a blind eye to the informal employment of Syrians to support businesses that need affordable labor. This approach, while beneficial for the economy, has drawn criticism for contributing to a significant black market for labor, which deprives the state of tax revenue and puts additional strain on public services, particularly healthcare. Many employers prefer Syrians because they are willing to work under conditions that local workers eschew, including low wages and a poor work environment.

Erdogan’s stance on keeping Syrians in Turkey also has long-term political implications, including the effects on elections. Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Erdogan has advocated for an open-door policy towards Syrians, a position that has won him significant popularity and affection among the Syrian population in Turkey. According to Ministry of Interior data, as of November 2023 the number of Syrians who had acquired Turkish citizenship stood at 237,995, with this number steadily increasing. In a 2019 statement Erdogan emphasized the importance of expanding the citizenship process, saying, “Why? Once they become citizens, they can find jobs, work with any institution, and contribute.”

In Turkey’s current presidential system, where every vote is important, Syrians may not yet play a decisive role in elections, but their votes are expected to become increasingly valuable in the near future. As Erdogan plans his re-election campaign or envisions a scenario where a family member takes his place, the support of Syrians will become even more crucial. Additionally, with constitutional amendments that the government is preparing to propose in 2025, such as the shift to a single-round presidential election in which the candidate with the most votes wins, the significance of the Syrians’ votes could rise further. Under Turkish law, a person can vote in the first election held after they become a citizen, and this is likely to increase Syrians’ political influence. The opposition has raised concerns, alleging that citizenship registrations are completed with commonly used Turkish names to prevent Syrians from drawing attention as new citizens. This has led to opposition groups’ checking birthplaces first in the election records to identify Syrian voters. Furthermore, in 2022, the government permitted citizens to change their names via the e-Government portal, sparking accusations that this move was intended to allow Syrians to replace their Arabic names with Turkish ones. While name changes typically require a court petition in Turkey, this policy change fueled suspicions that the government was facilitating Syrians’ integration into the political landscape.

It’s no secret that Syrian migrants in Turkey have become a key bargaining chip between President Erdogan and the European Union. In exchange for keeping refugees in Turkey, the Erdogan government not only receives financial aid but also benefits from the international community overlooking its poor human rights record. Following the regime change in Syria, EU member states suspended asylum applications for Syrians, and some countries have offered financial incentives to encourage their return. However, many Syrians, disillusioned with the economic and social hardships in Turkey, are increasingly looking to EU countries for a better life rather than returning to their home country.

Not surprisingly, just few days after the regime change in Syria, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made an official visit to Turkey, on December 12. During a joint press conference with President Erdogan, Von der Leyen announced that the EU would allocate an additional 1 billion euros to Turkey for Syrian refugees. This follows the EU’s previous commitment under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey (FRIT), which provided 6 billion euros in aid to support refugees in the country. FRIT is designed to fund projects in key areas such as humanitarian assistance, education, health, municipal infrastructure and socioeconomic support, with projects running to mid-2025.

Although the EU has implemented mechanisms to ensure proper oversight of how these funds are spent, it’s widely acknowledged that government-aligned companies and associations have profited significantly from these financial resources.

It is clear that Erdogan will not easily part with Syrians since they bring economic, electoral and diplomatic gains. However, if he fails to improve the struggling economy in the coming years, people will likely view Syrians still residing in Turkey as a serious issue and complain about them. The opposition will undoubtedly bring this topic to the forefront in order to gain the votes of these dissatisfied people.

Certainly, how the new regime in Syria progresses and whether the country will provide a suitable economy and social environment for the return of those who have left are equally important. It is also necessary to keep in mind that the implementation of these changes in the short term is not realistic.