Levent Kenez/Stockholm

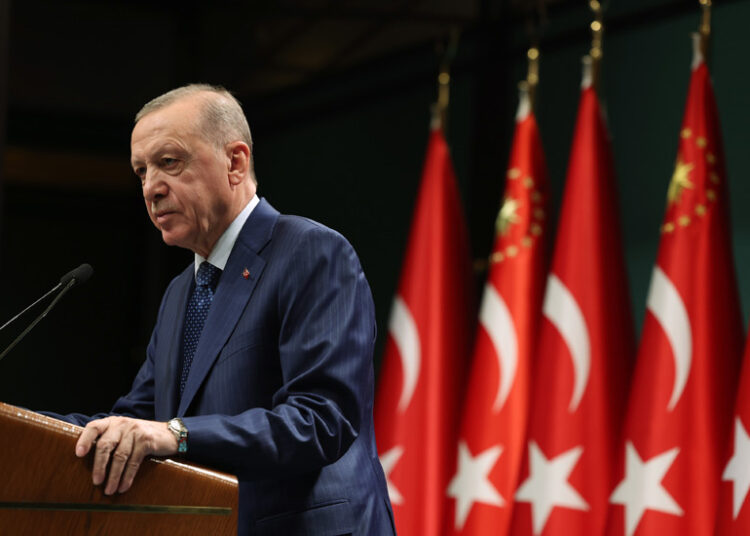

The government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan aims to punish dissidents as agents through an amendment to the Turkish Penal Code (TCK). The new regulation, expected to soon be presented to parliament for approval, is anticipated to be enacted before the legislature breaks for summer recess on July 1.

According to reports in the pro-government media, a series of proposals called the 9th Judicial Package includes new penalties for espionage under the umbrella of what is called “Agents of Influence,” previously absent from the TCK. The term will be added to the definitions of “espionage” and “spying” in the code.

The amendment aims to identify individuals who influence public opinion by disseminating propaganda against Turkey, although appearing to favor Turkey’s interests. Additionally, people propagating anti-Turkey views via social media will also be classified as agents of influence under the new regulation. These individuals are defined as those who disrupt the country’s economic, social or public order.

Increasing penalties for espionage are also on the government’s agenda. According to the draft amendment, offenses under the title “Crimes Against State Secrets and Espionage” in the TCK, which involve destroying or obtaining documents related to state security or its internal or external political interests, could result in prison sentences ranging from eight to 12 years. People who commit the same crime during wartime could face life imprisonment, while those obtaining information regarding state security could incur sentences ranging from three to eight years. Life in prison is proposed for individuals who disclose classified information for purposes of political or military espionage.

Justice Minister Yılmaz Tunç, following recent police operations targeting Israeli spy networks in Turkey, hinted that the government was working on new legislation to prevent foreign countries from spying in Turkey.

In a series of operations earlier this year, Turkish authorities detained dozens of people suspected of planning kidnappings and engaging in espionage for Israeli intel service Mossad, leading to the arrest of more than 20 suspects. Tunç said on March 8 that 63 people had been arrested in Turkey for alleged espionage for Israel since 2021, which rose to 65 with the arrest of two others in April.

The amendment proposed by the Turkish government shares similar intentions with Russia’s foreign agent law, which Russian President Vladimir Putin has utilized to imprison or intimidate international journalists who refuse to register as foreign agents. Furthermore, Georgia is currently preparing to enact a foreign agent law akin to Russia’s. On Wednesday the European Union cautioned Georgia that the adoption of such a law would hinder progress toward EU membership. On May 1 thousands of Georgians, including many young people, staged a large protest against the law in the capital city of Tbilisi. Tens of thousands of Georgians have taken to the streets to oppose the legislation, fearing it will undermine Georgia’s aspirations for Euro-Atlantic integration.

The Erdogan regime in Turkey, with its media influence and control of the judiciary, can easily label or punish opponents as terrorists, spies or traitors. Turkey faces serious problems regarding judicial independence. Courts including the Constitutional Court are under the tight control of the Erdogan government. According to the 2023 World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index, Turkey was ranked 117th out of 142 countries, dropping one rank compared to 2022. The country was ranked 137th in terms of constraints on government powers and 133rd in fundamental rights.

In 2022 Turkey passed a highly controversial media law that has faced strong criticism from legal experts and journalists for introducing censorship of the media. It also included provisions for censorship and protections in favor of the Turkish intelligence agency (MİT).

Under the new law if there’s reasonable suspicion that documents belonging to MİT are used in publications, MİT has the authority to take action to block the content, and journalists possessing such documents may face criminal prosecution. Regardless of the accuracy of the news, the use of MİT documents in reporting is prohibited.

With new articles added in 2022 to the TCK, the crime of “publicly disseminating misleading information” was detailed for the first time. A person who spreads disinformation is defined as “a person who publicly disseminates false information about the internal and external security, public order or general health of the country in a way that is suitable for disturbing the public peace, with the sole aim of creating anxiety, fear or panic among the public. Those who commit this crime will be sentenced to imprisonment of between one and three years. If the accused hides it or commits it within the framework of terrorist organization activity, the penalty will be increased by half.”