Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

The Turkish government, already under scrutiny by a global watchdog for serious shortcomings in combating money laundering and terrorist financing measures, has recently submitted a new bill that will make it difficult to graduate from increased monitoring, which is commonly referred to as being on the “grey list.”

The bill, submitted to parliament by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) on November 24, includes several provisions aimed at significantly reducing or entirely eliminating corporate taxes for companies and income taxes for individuals operating abroad if they transfer all or a portion of their earnings to Turkey.

The bill, presented as part of an incentives package to bolster Turkey’s troubled foreign exchange currency reserves, were criticized by the opposition as a new tactic to attract questionable funds to Turkey.

“[I]t lacks clarity regarding how the source of the funds to be brought into the country will be audited. It is unacceptable for shell companies that transferred their assets to tax havens and offshore accounts to return these assets to our country with a type of wealth amnesty package,” wrote opposition lawmaker Selim Temurci in his dissenting opinion to the Planning and Budget Committee report.

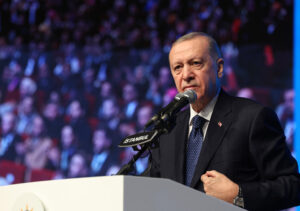

Other members of the committee and, subsequently, lawmakers in the General Assembly echoed similar concerns. Ahmet Davutoğlu, a former prime minister, described the bill’s purpose as a money laundering effort by the government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Turkey has already become a haven for money laundering activities orchestrated by organized crime syndicates and drug traffickers. Numerous terrorist groups have been discovered utilizing the Turkish financial system to facilitate funds transfers.

The transformation of Turkey into a hub for such activities has been facilitated in recent years by the Erdogan government. The administration has introduced various wealth amnesty provisions, promising no auditing and no imposition of criminal or administrative measures for funds brought into Turkey.

Article 59 of the bill provides both partial and complete tax exemption for funds brought in from abroad:

The bill appears to be following a similar pattern, albeit in a more sophisticated manner than its predecessors, by incentivizing cash transfers to Turkey without posing questions about their origin.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog, placed Turkey on the grey list in October 2021. Subsequent reviews have maintained Turkey’s status on the same list, citing a lack of strategic measures to combat money laundering and terrorist financing activities.

Four articles in the bill envisage that if companies bring profits earned abroad to Turkey, half of these gains are exempt from income or corporate taxes. The 50 percent tax break is applied to services such as architecture, engineering, design, software, education and health services provided abroad and is increased to 80 percent if all the revenue is brought into Turkey.

A bombshell revision was buried in the last paragraph of Article 59 of the bill, which states that “the president is authorized, within this article, to individually or collectively reduce the tax rates related to the tax burden to zero or increase them up to the corporate tax rate, to reduce other rates individually or collectively to zero or increase them up to 100 percent.”

In other words, President Erdogan can authorize a full tax exemption for profits transferred to Turkey if he decides to do so, without any legislative or judicial review of his decision.

This revision has sparked an uproar among the opposition, claiming that President Erdogan is usurping the legislative body’s main authority, which is to impose taxes and approve ways of collecting taxes. Article 73 of the Turkish Constitution clearly states that levying taxes is exclusively under the jurisdiction of the parliament.

To limit debate on the bill, the government buried the proposed changes in an 86-article omnibus bill that introduces a wide array of changes to 31 pieces of legislation. Half of these changes are related to alterations in tax regulations. The legislative impact study report about the proposed changes was handed over to the committee members just before its meeting on November 28, limiting the opposition’s ability to thoroughly review the assessment.

Furthermore, no stakeholders, such as unions, citizens interest groups and others, were invited to the committee to present their views on the bill. They were not part of any discussions when the bill was drafted by the government, either. The committee, dominated by majority lawmakers from Erdogan’s party and its ultranationalist allies, approved all changes in two days without providing much opportunity for the lawmakers to deliberate on the bill.

Although many of the changes fell within the jurisdiction of other parliamentary committees, such as the committee on Public Works, Planning, Transportation and Tourism, as well as the Constitutional Committee, none of them included the bill in their agenda. They did not undertake a review and debate, even though the Speaker’s Office referred the bill to these committees to seek their opinion.

The committee quickly sent the bill to the General Assembly, where half of its articles were adopted at the December 7 session. The rest will be adopted after the assembly finalizes the budget.

The opposition argued that the changes would create more challenges for Turkey, especially given the country’s already heightened monitoring by the FATF. They expressed concern that the bill could undermine Turkey’s efforts to remove itself from the grey list.

According to a report issued by the FATF in July 2023, Turkey still exhibits strategic deficiencies in complying with the recommendations made by the FATF. The report urged Turkey to undertake more thorough money laundering investigations and prosecutions as well as to conduct more financial investigations in terrorism cases.

Opposition lawmaker’s dissenting opinion on the bill on the grounds that it will be used for money laundering and worsen Turkey’s case with the FATF:

To address these deficiencies and enhance its anti-money laundering/combatting the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regime, Turkey would need to take additional measures. This includes strengthening its financial regulatory framework, intensifying law enforcement efforts and fostering international cooperation to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing activities.

The widespread abuse of the Turkish financial system by various criminal elements, including mafia groups, drug traffickers, organized crime syndicates and terrorist organizations over the past decade, is widely attributed to the permissive political environment fostered by the government of President Erdogan.

The mechanism employed by the Erdogan government to attract illicit funds as well as legally obtained but undeclared wealth is referred to in Turkish law as the “wealth amnesty,” or “varlık barışı” in Turkish. Wealth amnesty legislation has been passed multiple times in the Turkish Parliament, largely due to President Erdogan’s majority control of the legislative body. The most recent adoption of such an amnesty occurred last year when an amendment to a bill was presented to parliament by Erdogan’s ruling party, the AKP, and it was quickly adopted by the General Assembly.

According to the amendment, both individuals and entities had until March 31, 2023 to bring in cash, gold or other capital wealth from abroad that was not previously disclosed in Turkey. The amendment does not permit any audit or investigation into such assets under any circumstances, providing total immunity for money launderers, drug traffickers and others who transfer their wealth to Turkey. Individuals who were already under investigation by government auditors will also be able to exploit this amendment by claiming that the wealth under audit was obtained through such transfers.

The government would not impose any taxes on such transfers if the transferred funds were kept in a bank for at least a year. It was clear that the amendment was catering to crime syndicates and allowed them to launder money using Turkey’s banks and its financial system.

The opposition claims that the new tax breaks or exemptions for foreign currency in the bill submitted in November are a novel approach to providing a wealth amnesty.

The lack of transparency and concerns over potential money laundering, exemplified by the wealth amnesty bills, have contributed to Turkey’s continued placement on the grey list by the FATF since 2021.

Turkey has submitted an action plan to the FATF to end the enhanced monitoring, which has negatively impacted Turkey’s financial and economic standing. The heightened risk premiums in borrowing indicate that international lenders perceive increased risks associated with lending to Turkey, making it more expensive for the country to borrow funds. Furthermore, being on the grey list has posed challenges for the Turkish government in attracting foreign investment, particularly at a time when the country is already grappling with financial hardship and economic challenges.

The bill represents a rollback of actions taken by the government since 2021 to address shortcomings highlighted by the FATF. It is expected to impede progress and create more uncertainty in the AML/CFT regime, which could contribute to eroding the trust of international bodies like the FATF and financial markets. This, in turn, may make it harder for Turkey to regain its standing and attract foreign investment.

Turkey has not only permitted organized crime groups and terrorist organizations to utilize the Turkish financial and banking system for fund movement but has also misused measures and mechanisms intended to combat money laundering and terrorism financing for political purposes. In recent years, numerous foreign governments, intergovernmental organizations and nongovernmental human rights groups have expressed concern about the abuse of AML/CFT measures to suppress dissent, silence opposition and punish legitimate groups critical of the government’s policies.

The politicization of institutions responsible for combating financial crimes, such as the Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK), the body that coordinates with the FATF, remains a serious concern as it undermines the independence and effectiveness of these bodies. The removal of senior police chiefs and top administrators in the Interior Ministry, coupled with the politicization of MASAK, raises questions about the impartiality and credibility of MASAK’s actions.

Currently, MASAK is being utilized to generate reports that are manipulated to target legitimate businesspeople, journalists and human rights activists under the guise of fighting terrorism. This poses a serious threat to the rule of law and fundamental human rights in Turkey. In 2021, the year Turkey was placed on the FATF grey list, the Erdogan government confiscated the assets of journalists on fabricated terrorism financing charges as part of a crackdown on freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

Law enforcement and judicial institutions in Turkey are perceived as being dependent on political signals from the government, lacking the ability to act impartially and without bias. Consequently, actions taken to combat financial crimes, including money laundering and terrorism financing, are seen as being influenced by political considerations rather than being solely based on evidence and the rule of law.

With the bill, the Erdogan government, once again, reaffirmed the fact that it has no real interest in restoring the rule of law, respecting rights and freedoms or genuinely cracking down on criminal enterprises.

Furthermore, Turkey’s new economy czar, Mehmet Şimşek, who is tasked with steering Turkey off the FATF’s grey list, does not inspire much confidence. His office drafted the new bill without involving stakeholders or opposition lawmakers. As a former finance minister in the Erdogan government, Şimşek has been accused of enabling corrupt practices and political interference in financial institutions such as MASAK.