Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Ahmet Cemalettin Çelik, the number two at Turkish intelligence agency MIT, has been working to keep his boss, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in power as the country heads towards elections in May.

Çelik, a long-time Erdogan loyalist and political appointee, had in the past played critical roles in aiding and abetting unlawful practices that shored up Erdogan’s power during critical periods. He went after police officers who had uncovered Erdogan’s illegal activities involving a number of suspects, including a one-time al-Qaeda financier, and made sure they were punished for simply doing their jobs.

Abusing his position overseeing electronic surveillance and signal intelligence, he executed illegal plots to eavesdrop on Erdogan opponents and fabricated evidence to falsely accuse them as well as leaking information to influence the political debate.

Çelik oversaw intelligence operations in foreign countries, especially in Europe and North Africa, and positioned himself as the key intel official who sits in the room with Europeans and Americans to sort out issues that would help promote Erdogan. Be it talks with Sweden and Finland on their NATO membership prospects or resolving outstanding issues with White House officials, Erdogan consistently embedded him in Turkish delegations.

Not much is known about his background, but it is clear that Erdogan trusts him implicitly, to the extent that Çelik has his eyes and ears in sensitive talks from which Erdogan hopes to derive political and personal benefit, sometimes at the expense of Turkey’s national interests.

Growing up in a conservative and religious family with six siblings, Çelik was guided by his father, İbrahim Çelik, an imam and preacher. He studied political science and international relations at Ankara University and started working for the government in an entry level job at the Office of the Prime Ministry after graduation. He helped write draft bills, legislative amendments and government decrees. He climbed the ladder quickly and became head of security at the office, protecting Erdogan.

In 2012 Erdogan assigned him to MIT, where he worked in signal intelligence and electronic surveillance under MIT Undersecretary Hakan Fidan, another Erdogan loyalist who has been running the agency since 2010. When Erdogan faced a massive corruption scandal that incriminated him and his inner circle in an Iran sanctions-evasion scheme, Çelik was one of the few people Erdogan turned to for help in weathering the crisis.

The bribery investigations, which were made public December 17 and 25, 2013 by public prosecutors in Istanbul, unmasked Erdogan’s corrupt scheme by revealing overwhelming evidence including court-approved wiretaps. On December 23, 2013, only four days after the first corruption probe became public knowledge, Erdogan asked Çelik to leave his job at MIT and become head of the Telecommunications Directorate (TİB), a key agency that fulfills court orders for wiretapping suspects in criminal investigations.

Erdogan was in a panic because he didn’t know what other investigations prosecutors were pursuing against suspects that might have implicated or incriminated him further. By controlling TİB through his loyalist, he would know what court warrants were sent to the agency and would have a chance to derail the probes.

That is exactly what Çelik did. As soon as he arrived at TİB, he removed department heads and branch chiefs and replaced them with personnel from MIT. The wiretaps in TİB’s possession were studied, and all the judges who had granted authorizations for technical surveillance and all the prosecutors who requested warrants for surveillance together with members of the Security General Directorate who were involved were identified.

In the end nearly 3,000 judges, prosecutors and police officers who had submitted requests for wiretaps over the years were listed and marked for reassignment or dismissal.

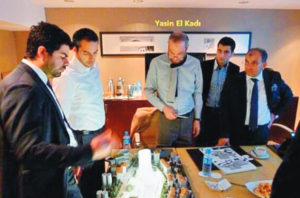

One of the tasks Çelik was given by Erdogan was to determine who was involved in the wiretapping of his associates, including Yasin al-Qadi, a Saudi national, at one time designated an al-Qaeda financier by both the UN Security Council and the US Treasury. In a top secret document obtained by Nordic Monitor, Çelik wrote on March 24, 2014 that he was able to identify who in the police department had downloaded wiretaps from TIB servers and sent the list to Erdogan loyalists in the government in order to punish the police officers who simply did their job as part of a criminal investigation under orders from prosecutors.

Top-secret letter signed by Ahmet Cemaleddin Çelik targeted police officers who monitored one-time al-Qaeda financier Yasin al-Qadi, a close associate of Turkish President Erdogan:

Al-Qadi was designated as al-Qaeda financier by the US Treasury, and the United Nations Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee listed him under terrorism as a part of Security Council resolutions. The Turkish government also issued an official circular designating him as a terrorist, barring him from entering Turkey or transferring funds in the country.

Yet he secretly made trips to Turkey including on Erdoğan’s official plane in 2011 when he was still under sanctions, followed by more trips under Erdogan’s protection, meeting with Erdogan, MIT chief Hakan Fidan and others. Al-Qadi was later removed from the UN list, followed by the US Treasury delisting his name.

Another secret letter signed by Çelik on February 27, 2014 shows he was very much involved in a witch hunt to punish police officers who had listened to and transcribed court-authorized wiretaps and sent them to the prosecutor’s office as part of a criminal investigation.

Secret letter signed by Ahmet Cemaleddin Çelik that reveals he went after officials who unmasked Erdogan’s massive corruption network in criminal investigations:

After putting TİB fully under Çelik’s control, Erdogan rushed a bill through parliament on February 5, 2014 granting significant powers to the agency to monitor GSM networks, social media platforms and the internet, where a large amount of damning evidence on the corrupt practices of the government was leaked and shared. Çelik set up a special unit called the Sosyal İzleme Merkezi (Social Monitoring Center) to track social networking sites such as Twitter and Facebook. The government started running surveillance of internet users 24 hours a day and shared the information with MIT. The new unit also tracked GSM network lines to monitor communication apps such as Viber, Signal and WhatsApp.

TİB was also given the authority to block access to specific websites without the need for a court order, reversing an earlier practice. The new bill also granted broad immunity from prosecution to TİB personnel unless permission was granted by the TİB president and the government. The provision was added to the bill because people in TİB were reluctant to share data with others for fear of facing criminal charges in the future.

Empowered with the new legal provisions, TİB blocked Twitter and later YouTube in March 2014 and did not enforce local courts’ rulings to lift the blocks. It took a Constitutional Court judgment to force TİB to act.

Another plot devised by Çelik at TİB was to tamper with system logs to fabricate evidence against critics of the Erdogan government, especially members of the Gülen movement, a group that is opposed to the repressive practices of the Turkish government. In fact, a whistleblower on April 22, 2014 sent a detailed letter to media outlets revealing what Çelik was up to at the agency. The anonymous source said he worked at TİB and personally witnessed the plot unfold.

According to the whistleblower’s account, Çelik ordered the new people he brought from the intelligence agency to enter the electronic serial numbers (ESNs) of the mobile phones of prominent people into the system and then erase them. These deleted records would later be recovered by technicians as if they had discovered a major conspiracy. The goal was to falsely accuse those who were dismissed from TİB of wiretapping unsuspecting people and smear them in public.

The whistleblower, who identified himself as an employee of TİB at the time, said he was going public with the information because he didn’t want to be part of a smear campaign that could endanger the lives of many innocent people who had served the institution.

In May 2014 another scandal involving Çelik made headlines in Turkey. On May 7, 2014 a former expert who had worked at TİB’s data processing bureau filed a criminal complaint with the Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office against TİB President Çelik and two department heads at the directorate.

In his petition the complainant claimed that Çelik had engaged in many unlawful actions since he was appointed TİB president and had put immense pressure on staff at the directorate and sacked those who did not comply with his unlawful orders. The complainant was one of them, the petition said. The complainant also confirmed the April whistleblower’s allegations, saying two department heads working at TİB tampered with its system logs under instructions from Çelik. According to the expert, Çelik and other officials at the directorate were engaged in efforts to fabricate evidence to accuse certain people of criminal behavior.

He also argued that he was illegally removed from his job after the former president of TİB was reassigned by the government. He said he was working at the data processing bureau and that the Information Technologies and Communications Board (BTK) was authorized to remove or appoint experts to the bureau. “However, I was fired unlawfully as per the directive of the head of TİB,” he stated.

In June 2014 TİB came under the spotlight when news that some TİB employees were unlawfully interrogated at agency headquarters for hours by Çelik and other officials including MIT agents. A complaint by a former employee, identified only by the initials H.D., was filed with the prosecutor’s office and revealed that Çelik and unidentified people accused him of committing crimes and interrogated him although they had no legal authority to do so. The interrogation lasted roughly seven hours, until just past midnight. Çelik also participated actively in the questioning, asking what H.D.’s political viewpoints were.

H.D. objected to the questioning, saying such an interrogation was unlawful and that he wanted to call his lawyer, which they refused to allow him to do. “A bald officer with a goatee threatened to lead me handcuffed and by the nose in front of my colleagues,” said H.D. He also wrote in the complaint that the officers recorded the interrogation with their mobile phone cameras.

The Erdogan government abolished TİB in August 2016, and the wiretaps requested by law enforcement agencies and authorized by the courts were transferred to the BTK. As his mission was complete, Çelik returned to the spy agency to serve as deputy intelligence chief.

Today Çelik runs the spy agency’s external relations, visiting foreign countries and participating high-level meetings representing the intelligence service. He was a member of a delegation when Turkish officials attended a meeting in January 2019 to talk to then-US National Security Advisor John Bolton and Joseph Dunford Jr., the then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and other American officials in Ankara.

He was also present during tense talks held among Turkish, Swedish and Finnish delegations over the Nordic countries’ bids to become members of the NATO military alliance.

Turkish intelligence operations in Europe, Libya and the breakaway Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus are included in his portfolio as well.

One of his brothers, Ömer Faruk Çelik, a long-time political Islamist, is a mayor in the Şehzadeler district of Manisa province. He ran on Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) ticket after serving in various positions in the party’s provincial administration.

Another brother is Mustafa Halit Çelik, a lawyer who works for the government-run General Directorate of Foundations (Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü). He has long been actively involved with the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (İnsan Hak ve Hürriyetleri ve İnsani Yardım Vakfı, or IHH), described as the logistics supplier for al-Qaeda’s global operations. He was a board member at the IHH and ran the charity’s Izmir branch. The IHH works closely with Turkish intelligence and helps support radical jihadist groups in Syria including al-Qaeda.

Abdurrahman Çelik, another brother, works for the Religious Affairs Directorate (Diyanet). In the past he worked as an imam under the Turkish-Islamic Union for Cultural and Social Cooperation in Austria (ATIB), an organization that is linked to the Turkish government.

Ahead of the May 14 presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey, MIT’s Çelik has reportedly been involved in various schemes to provide a boost for Erdogan in his election campaign and abusing the intelligence agency’s resources and directing its capabilities to undermine the opposition bloc led by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu.