Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

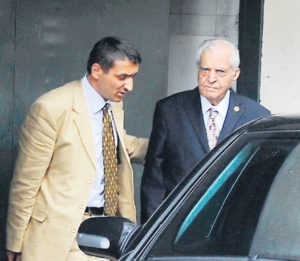

Yıldırım Demirören, son of the late businessman Erdoğan Demirören and a close associate of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has built his wealth on the unlawfully seized assets of a businessman from the minority Greek (Rum) community who was brutally murdered in Turkey,

The confidential documents that implicated Demirören’s family in the murder and asset theft were incorporated in a court file for the first time in 2018 thanks to efforts by journalist Mehmet Baransu, who testified how he managed to get ahold of classified intelligence documents and government communiqués.

The court documents obtained by Nordic Monitor give the horrific details of the murder and theft in a chilling environment that still continued a decade after the September 6-7, 1955 mob attacks on the Greek minority in Istanbul and Izmir, which were clandestinely orchestrated by Turkish authorities.

Baransu, a prominent investigative journalist who broke dozens of agenda-setting headline stories in his career, has been wrongfully jailed by Erdoğan since March 2015 as part of a government campaign to muzzle critical voices in the Turkish press and intimidate investigative journalists.

Journalist Mehmet Baransu’s testimony in court in October 2018:

Yet, even from behind bars, Baransu managed to put the murder and corroborating evidence into the official record when he appeared in court to defend himself against the ludicrous charges filed by the government to keep him in prison for eternity. He used his defense to explain how the Demirören family enriched themselves at the expense of a Turkish-Greek businessman and how the case was hushed up by the authorities. This was the first time the allegations against Demirören became part of the proceedings in in a court that tries serious offenses in Turkey.

Testifying at the Istanbul 23rd High Criminal Court in October 2018, Baransu provided a detailed account of how he obtained documents from a Demirören family member named Ferruh Karakaş, a nephew of Demirören senior and cousin of Demirören junior, who shared documents and letters that exposed how the murder and theft took place. He also received a cache of documents from other sources including the former lawyer of a crime boss who was asked by Demirören to kill the surviving member of the Greek family.

Karakaş shared the documents with Baransu amid a long-running family feud over the distribution of assets that had erupted within the Demirören family. Disgruntled family members who were cheated by Erdoğan Demirören and his son of the estate left by their grandfather threatened to go public and thought media exposure might give them leverage to negotiate with Erdoğan Demirören.

Turkish intelligence agency MIT’s secret report on the murder of the Turkish-Greek businessman:

According to the court testimony of Baransu, Karakaş approached other journalists to pitch the story but none dared write the exposé out of fear of repercussions from powerful business magnate Demirören and his associates in the Turkish government. Given the fact that the murder was covered up with the involvement of police, the intelligence agency, politicians and other high-ranking officials, nobody dared open Pandora’s box.

Baransu was different. He agreed to write the story provided that the allegations checked out and that the claims were verified by other sources and witnesses. He did his due diligence and worked on the story for months, reviewing hundreds of documents, going through old newspaper articles and interviewing dozens of current and former Turkish government officials as well as nongovernmental sources that had knowledge of the murder. The story was finally published in the independent Taraf daily on May 20, 2013, two years before the Erdoğan government decided to shut down the newspaper.

Karakaş’s aunt, Nurhan Aksoy, who died of cancer on May 15, 2008, left a will instructing her children to expose her brother Demirören’s dirty laundry to the public and handed over handwritten letters along with classified documents to support the exposé. Among those documents was a reference to a report written by MIT in 1982 that implicated Demirören as the murderer of two people whose assets were later transferred to him.

That report mysteriously disappeared, and copies of it in several government agencies were destroyed, although its content was mentioned in other documents. After a long search, Baransu managed to find a copy from a source he never expected months later.

The victim of this terrible saga was a Greek man named Yorgo Papadopulos (in official records he was known as Yorgi Papadopulo), the owner of Arşimidis Müessesesi Otomobil Malzemesi Ticaret Türk Anonim Şirketi (Arşimidis), an auto parts dealer. His roots were in the small Turkish province of Niğde in the heart of Anatolia where his father Mina worked as a farmer. His family moved to Istanbul when he was 10, and he was educated there.

He started working for Arşimidis, a company that sold car and bicycle parts, in the 1930s, became a shareholder in time and eventually was named CEO of the company. He spoke English, French, German, Turkish, Greek and Arabic. He married a Greek woman named Afroditi. The couple had two children, but none survived.

Trade registry records from 1957 that show Yorgo Papadopulos as the owner of Arşimidis:

The multimillionaire couple mysteriously disappeared from the face of the earth in 1963, according to a family acquaintance who pursued a decades-long search for traces of them. Trade registry records for the company reviewed by Nordic Monitor indicate that Yorgo was alive at least until 1967 since his name was recorded in company minutes, meetings and filings. Those documents that were submitted to the support trade registry filings may very well have been falsified as Baransu later discovered many forgeries in the company documents.

A filing made on October 31, 1967 mentioned that Yorgo had sent a letter from Geneva on March 20, 1967 saying that he had resigned as CEO and sold his shares. A Turkish man named Necdet Çobanlı, who was Yorgo’s legal counsel, replaced him as owner and CEO of the company. On April 15, 1977 Erdoğan Demirören, a deputy to Çobanlı, took over the company according to the records, and Çobanlı resigned. In January 2013 the company ceased operations and was merged with real estate investment firm Taksim Gayrimenkul Yatırımı ve Danışmanlık A.Ş., which is also owned and controlled by the Demirören family.

Letter of resignation of Yorgo Papadopulos that was allegedly sent from Geneva was mentioned in a trade registry filing in 1967:

It turned out that the “gang of four” — Çobanlı, Demirören, Adnan Başer Kafaoğlu (a financial advisor who later became a high-ranking bureaucrat and served as finance minister) and Vural Arıkan (an accountant who also later became finance minister) — conspired to murder the Greek businessman and his wife and illegally seize their assets. They thought nobody would bother to investigate and claim their estate since they believed the couple had no relatives.

According to government documents, it was alleged that Demirören and another man identified only by the first name of Aliko strangled Yorgo with either a necktie or some sort of shawl in the businessman’s own car. Yorgo’s surviving family members believe his wife Afroditi was also murdered around the same time and that her body was set ablaze with gasoline in a remote location in the Halkalı district. The Arşimidis company and all the family’s assets were transferred to Çobanlı and his associates under fake documents. They thought they were in the clear and had gotten away with the murders and the unlawful seizure of assets.

Trade registry record that shows Demirören took over the Arşimidis firm:

What they didn’t know was that Yorgo was quietly looking for his relatives in Turkey when he was alive and had met a sister he never knew he had. The sister, Panayot, had converted to Islam and changed her name to Zeynep Aslan under circumstances that were not clear. She was married to a man named Sıtkı Arabulan and was living in Mersin province.

The sister reached out to Çobanlı to inquire about Yorgo. Çobanlı responded in a letter on December 13, 1967 and said Papadopulos had passed away in Geneva and that his wife went back to Greece. As proof, he sent a news clip published in Hürriyet the same day he wrote the letter that claimed Yorgo had passed away eight days earlier in Geneva after surgery and had left behind assets valued at 300 million Turkish lira. According to the article, the businessman was buried in Geneva without informing his family members, friends or loved ones. Afrodit moved to Athens in Greece after that, the article alleged.

The Hürriyet story was entirely fabricated thanks to the efforts of Çobanlı and his associates’ influence at the daily. It was damage control amid panic and an attempt to create a plausible narrative to mask the murder and illegal transfer of assets after a family member emerged to claim their inheritance. The gang also created fake documents such as border entry and exit records by the police showing that the couple flew abroad but never returned. Baransu said the official stamps on the records were all forgeries.

Mehmet Baransu’s headline story in the Taraf daily on Arşimidis:

Yorgo’s newly found sister and her husband challenged the asset transfers and launched a legal battle that did not go anywhere even though a family court confirmed that she was in fact a sister to Yorgo and had a right to an inheritance. In the meantime, Çobanlı turned Arşimidis over to Demirören and moved to the US, where he lived off Yorgo’s seized assets.

It was a heroic Turkish couple who had befriended the Papadopulos family when they were alive that championed the campaign against the gang of murderers. The couple, medical doctor and retired colonel Hayri Esen and his wife Inayet Esen, forged close ties with Papadopulos after Afroditi became a patient of the doctor and was treated in his office. They were puzzled when the Papadopulos couple suddenly vanished without a trace and without a word.

First page of a story on Arşimidis in the Taraf daily:

Esen passed away in 1970, but Inayet, at the request of Arabulan, whom she knew from Mersin, continued the campaign to return the wrongfully seized assets to their rightful owner and see the murderers punished. Using her late husband’s network of friends in the military and government, Inayet started digging to find out what had happened to the Papadopulos family. In an interview she gave to the Turkish 2000’e Doğru (Towards 2000) magazine on November 6, 1988, she explained how she managed to find out what had happened to the Greek family and who had murdered them.

Inayet was discreetly told by an agent of Turkish intelligence agency MIT the details of the murder and how Demirören was personally involved in choking the businessman to death. The agent, a long-time friend of Inayet, told her that documents about the murder were kept in the archives of the Istanbul Governor’s Office. With this information, Inayet filed a complaint with the police and asked them to interrogate Demirören and his murder accomplice. But a then-police chief, Ahmet Atesli, who headed the homicide unit, threatened her with detention, saying she should not be stirring up trouble around an old case that he described as simply the death of an “infidel” long ago.

Second page of the story on Arşimidis in the Taraf daily:

In his investigation, Baransu discovered that Demirören received help from Istanbul’s then-police chief Hayri Kozakçıoğlu in creating fake documents that ostensibly showed the Papadopulos couple’s foreign trips and justified the illegal asset transfers. Among the forged documents was a passport belonging to Afroditi with exit stamps at the border as well as a power of attorney that allegedly had Afroditi’s fingerprint indicating her consent. The documents bore official stamps and signatures that were later proven to be forgeries in a family dispute court case in Istanbul concerning the distribution of assets from an estate. Apparently all the documents were created to justify the transfer of assets.

Kozakçıoğlu later became a governor of Istanbul and did everything he could to derail the investigation into the murders and asset seizure. In return Demirören employed Kozakçıoğlu’s son Ferhan in his own firm for a sizable salary. Although the son had an office on the same floor as Demirören, he rarely showed up for work but kept receiving big paychecks every month.

Another MIT report on Arşimidis:

Although she was stonewalled in her initial inquiries, that did not stop Inayet from looking further. She wrote petitions to the National Security Council as well as commander of the martial law administration in Istanbul after a military coup in 1980. None of her inquiries were successful in getting the authorities to file charges against Demirören and his associates. She claimed the Demirören gang wielded significant influence over the government and paid numerous bribes to make the case go away. Inayet’s complaints nevertheless managed to move the wheels of government and helped register and investigate claims.

Baransu’s exposé in 2013 accompanied by official documents rattled Turkey when it revealed that the Turkish authorities knew about the murders. Both the police and intelligence agency wrote reports about the murder of Yorgo and his wife and implicated Demirören as the killer. According to General Staff documents, an inquiry was launched after Inayet filed a complaint on October 21, 1981 with the military authorities that were running the country at the time.

Two days later the General Staff referred the complaint to the Martial Law Coordination Presidency (Sıkıyönetim Koordinasyon Başkanlığı) in Istanbul, a body that governed the city under military rule. A second but anonymous complaint was also received by the General Staff around the same time, and that was forwarded to Istanbul as well.

Inayet Esen’s interview in a Turkish magazine about the murders:

The Martial Law Administration (Sıkıyönetim Komutanlığı) in Istanbul sent the complaints to intelligence agency MIT for investigation. After completing its own probe, MIT sent two letters to the General Staff, the first on January 28, 1982 and the second on April 8, 1982, about the results of the investigation. The MIT letters were signed by intelligence chief Burhanettin Bigalı.

The General Staff asked the First Army (1. Ordu), which was in charge of enforcing martial law in Istanbul after the coup, to investigate the allegations as well. The army also sent its findings to the General Staff, first on April 6, 1982 and then on July 16, 1982. None of the communications received by the General Staff from the two institutions refuted the allegations in the complaints. The General Staff merged all the reports and sent them to the Prime Ministry on August 20, 1982 for further action.

At this stage, the government is supposed to elevate the matter to a prosecutor’s office for a criminal investigation that would have certainly led to indictments and a trial. But the case languished in the office with no action.

The case file was submitted for review to Turgut Özal, who was elected prime minister in 1983 in the first election after the military transferred power to a civilian government. According to Baransu, who sourced the information from Demirören family members, the file was stolen from the prime minister’s desk by Özal’s wife Semra, who was a close friend of one of Erdoğan Demirören’s sisters. They had been meeting at a women’s group called Papatyalar (Daisies) in Istanbul.

The sister gave the document to Demirören and attached a note reading, “Semra Hanım handed me this document. It was sent to the prime minister’s attention. One of your enemies made this happen. She didn’t let Özal read it.” Testifying in court in 2018, Baransu said he had verified the handwritten notes of both the sister and Semra Özal that were found on the stolen case file.

The details of the murder were also verified by Mehmet Eymür, a retired MIT official who served in senior positions in the agency’s special bureau and counterterrorism and operations departments for many years. After Baransu’s report in Taraf, he shared what he knew of the case on his own website on May 27, 2013 and revealed the names of MIT officials who were involved in derailing the investigation and who helped the murderer evade justice.

He said MIT İstanbul Regional Chairman Osman Nuri Gündeş played a crucial role in hushing up the allegations. According to a leaked confidential intelligence report that was published in the Nokta magazine on September 4, 1988, Gündeş and his associates in the government were involved in extorting money from non-Muslim minority groups in Istanbul. It was similar to the protection money that mafia groups demand, and many people in the minority community had to pay for fear of retribution.

The report also mentioned the Arşimidis case and incorporated a detailed report drafted by the Istanbul police smuggling and intelligence unit (Kaçakçilik İstihbarat Şube Müdürlüğü) on November 23, 1984 that was also shared by the intelligence agency.

The report made clear that Demirören was involved in the murder of the Greek businessman and had illegally seized the victim’s assets with forged documents. The report also mentioned that Demirören threatened to have Arabulan, who was trying to secure a fair share from the state for his wife, killed by notorious mafia leader İdris Özbir, also known as Kurdish İdris (Kürt İdris) in Istanbul. After the threat, Arabulan, accompanied by Inayet, paid a visit to the mafia leader and told him about the conversation he had with Demirören and the threat of murder.

Özbir saw an opportunity to make money off the plight of Arabulan. Instead of helping him and his wife, the mafia leader demanded money from Demirören to keep it quiet and not disclose the secret documents he obtained from Arabulan. In the end, Özbir was paid 300 million Turkish lira by Demirören as hush money to not pursue the case. Özbir passed away at home in 2002.

In his court testimony, Baransu said that after his story was published in Taraf in May 2013, Erdal Ilikgöz, the former lawyer of Özbir, reached out to him and handed over the entire case file including classified intelligence documents about the murder. The documents, entrusted to the lawyer by the mafia leader before his death, had never been made public. Baransu wrote a follow-up story on the murder based on these new documents.

This is not the only murder Demirören was accused of being involved with. The MIT document implicated him in two other murders as well: an unnamed brick manufacturer and propane gas dealer Metin Çam, both of whom died under mysterious circumstances before their assets were confiscated by Demirören.

Baransu said he had verified claims in the documents by talking to government officials who had served between 1980 and 1990 and worked for months to make sure the story was a solid one. He submitted his article along with the official documents to the editorial board at Taraf. Everybody was excited about the exclusive story that was certain to set the agenda in Turkey. However, Oral Çalışlar, the newly assigned editor-in-chief who took over management of editorial policy after legendary Turkish author and critical journalist Ahmet Altan stepped down, was not enthusiastic.

The Erdoğan government was happy with Çalışlar, who killed the story and never ran it despite the objections of journalists and the entire team of editors at the paper. Today Çalışlar works for the Posta newspaper, owned by the Demirören family. He was rewarded by Demirören for killing the explosive story about the family’s dark past.

Baransu, frustrated, did not give up, however, and continued his investigation and even managed to get the General Staff to verify all the documents in his possession some 30 years after the murder was first recorded in military documents in early 1980s. He also learned that the case against Demirören was never closed and is still pending. Investigation case file No. 1984/1101, initiated by the prosecutor’s office in Beyoğlu, was later sent to the Sultanahmet Courthouse, where it vanished in the early 1990s. Baransu called his contact at the General Staff to make sense of the comment sent to Taraf and double checked whether the case was still open. In response, his contact said that was the case in the records of the General Staff. If it had been closed, the court would have informed the General Staff, which it never did.

After Çalışlar left Taraf, Baransu pitched his article again to the new editor-in-chief, Neşe Düzel, who took over the helm of the newspaper on April 27, 2013. Düzel agreed to publish it as well as the follow-up stories on the illegal business dealings of the Demirören family. Demirören, who was the owner of the Milliyet and Vatan newspapers at the time, made no comment on the story the day it was published. Later in a brief comment to the now-defunct Wall Street Journal Turkish edition, he said the allegations were all rubbish. His lawyer, Cemalettin Mutlu, said his client has never faced a murder investigation.

Demirören died on June 8, 2018 without being held to account for the murder and asset theft. His son Yıldırım now runs the family business and works closely with the Erdoğan government. With a $750 million loan from Turkish state lender Ziraat Bank, the Demirören group purchased Doğan Media on March 22, 2018, which included the Hürriyet newspaper, broadcaster CNN Türk and mainstream TV station Kanal D, turning all of them into government mouthpieces. Yıldırım reportedly never repaid the loan, and the government ignored parliamentary questions on its fate.

Today, the Turkish regime pursues the same policy of pillage and plunder by unlawfully seizing the assets of members of the Gülen movement, a group critical of the Erdoğan government, valued at tens of billions of US dollars. The courts, controlled by the government, fail to provide restitution to those whose wealth was stolen and redistributed to cronies of Turkish President Erdoğan.