Levent Kenez/Stockholm

The Turkish Ministry of Justice in a decree on Sunday demoted the head of an İstanbul court who opposed the transfer to Saudi Arabia of the case of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who was brutally murdered in the Saudi Consulate General in Istanbul in 2018, appointing the judge to a post below his seniority. In his statement to the media, the judge announced that he would retire in protest. It is ironic that the timing of the demotion roughly coincided with the Saudi crown prince’s visit to Ankara.

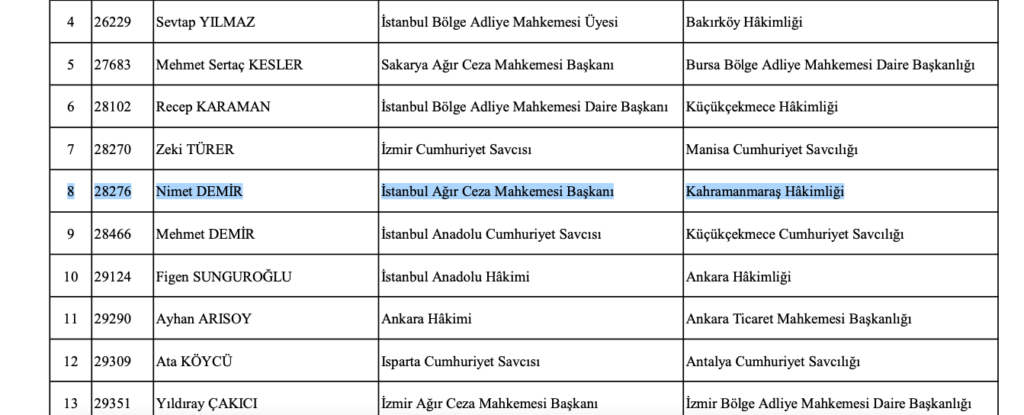

In April Nimet Demir, head of the 12th High Criminal Court, opposed the transfer of the file regarding the murder of Khashoggi to Riyadh. Moreover, he wrote a dissenting opinion after an objection made by Khashoggi’s lawyers was rejected by a majority vote in his court.

According to Turkish judicial procedure, an objection is made to the court whose numerical designation follows the number of the court where the trial was held. During a hearing at the 11th High Criminal Court in April, the decision to transfer the file to the Saudis was made, and Khashoggi’s lawyers appealed to the 12th High Criminal Court, where Demir is the presiding judge.

Indirectly criticizing the political decision taken by the government to restore relations between Turkey and Saudi Arabia, Demir claimed in his dissenting opinion that the transfer of the case to Riyadh contravened Turkish law.

“The life, property and honor ofJamal Khashoggi was under the guarantee of the Turkish state,” he wrote, adding that the reckless and brutal murder of Khashoggi carried out by Saudi operatives in İstanbul was an attack on Turkey’s trustworthiness as a country as well as on the honor and dignity of the state. He claimed the 26 defendants would be the judges in their own cases.

Demir also said it was weak to say, “What can we do, the Saudis won’t hand the defendants over to us.”

“I am of the opinion that the transfer of the case and the removal of the Red Notices for the defendants are incompatible with values such as justice, equality and honesty.”

Demir characterized the transfer of the case as the price for fixing the poor bilateral relations between Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

After his demotion on Sunday, Demir told Turkish media that he was not expecting such a decision from the government. Stating that he was trying to do what was necessary for the values of democracy, human rights and freedoms, Demir claimed that this is a stance that will always be criticized by authoritarian states and that he is the victim of that stance.

Announcing that he would leave the legal profession, Demir said he would soon send his petition for retirement to the ministry.

Describing himself as a conservative, he did not think that the government would go so far as to appoint him to a position beneath his seniority.

“I didn’t think they would dare do this, that they would be so reckless,” he said.

After the murder of Khashoggi in 2018, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan harshly criticized the Saudi regime, with which he had been angry since the Arab Spring, and especially targeted Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). There was also an intensive campaign in the pro-government media against MBS, whom Erdoğan described as “a bloody-handed murderer.” In an effort to put Salman into a more difficult situation, the Turkish government shared the evidence obtained by Turkish intelligence with foreign media outlets. Erdoğan declined the Saudi demand to share the evidence with them and claimed that it would be destroyed.

In response to the Turkish propaganda, Riyadh unofficially boycotted Turkish goods, a move that caused Turkish companies to lose a significant market share in the Gulf region.

However, immediately after the transfer of the case, Erdoğan made an official visit to Saudi Arabia, meeting with Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz and de facto ruler MBS on April 28. Claims by political observers that the termination of the Khashoggi case in Turkey was a prerequisite for the re-establishment of relations between the two countries proved to be right.

Meanwhile, MBS will make an official visit to Turkey on June 22. Speaking to reporters following Friday prayer, Erdoğan said he would be welcomed at the presidential palace in Ankara.

In the same decree published on Sunday, Judge Kürşad Bektaş, who voted in favor of the defendants in the Gezi protest trial and argued that there was not sufficient evidence to impose a sentence, was appointed as a prosecutor in the small province of Tokat. While the opponents claimed that this was also a form of punishment, the pro-government media argued that it was time for Bektaş to be transferred to a new position and that he was appointed to the city he had requested in order to be close to his hometown of Samsun.

Turkey frequently comes to the attention of the world with the pressure on lawyers, judges and prosecutors. Nordic Monitor previously reported that Turkey was put on notice by the United Nations for a systematic and deliberate campaign to crack down on judicial members with blatant abuse of counterterrorism laws in order to punish them for representing critics, opponents and dissidents.

A recent report dated April 22, 2022, submitted to the UN Human Rights Council by Diego García-Sayán, special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, highlighted the practice of Turkish prosecutors who routinely launch cases against lawyers on terrorism charges for activities undertaken in the discharge of their professional duties.

Prosecutors who follow the political guidelines of the government of President Erdoğan also associate lawyers with the alleged crimes of their clients, according to the report.

The UN reported that between 2016 and 2022 more than 1,600 lawyers were prosecuted and 615 were placed in pretrial detention. Four hundred seventy-four lawyers have been sentenced to a total of 2,966 years in prison on the grounds of membership in a “terrorist organization.”

In the aftermath of a coup attempt in 2016, 4,560 judges and prosecutors were dismissed and replaced by Erdoğan loyalists, many of whom were barely out of college and others who were politicians in the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). A total of 2,431 of the judges and prosecutors were detained on trumped-up charges. Some 30 percent of Turkey’s judges and state prosecutors were dismissed and/or jailed, part of a sweeping crackdown that has seen more than 130,000 people sacked or suspended from the military, police and the civil service.