Nordic Monitor/Stockholm

A Turkish journalist detained in Norway, where he went to apply for asylum, is fighting a legal battle against deportation to Turkey. If the journalist is deported, his arrest is considered certain given the previous actions of the Turkish government.

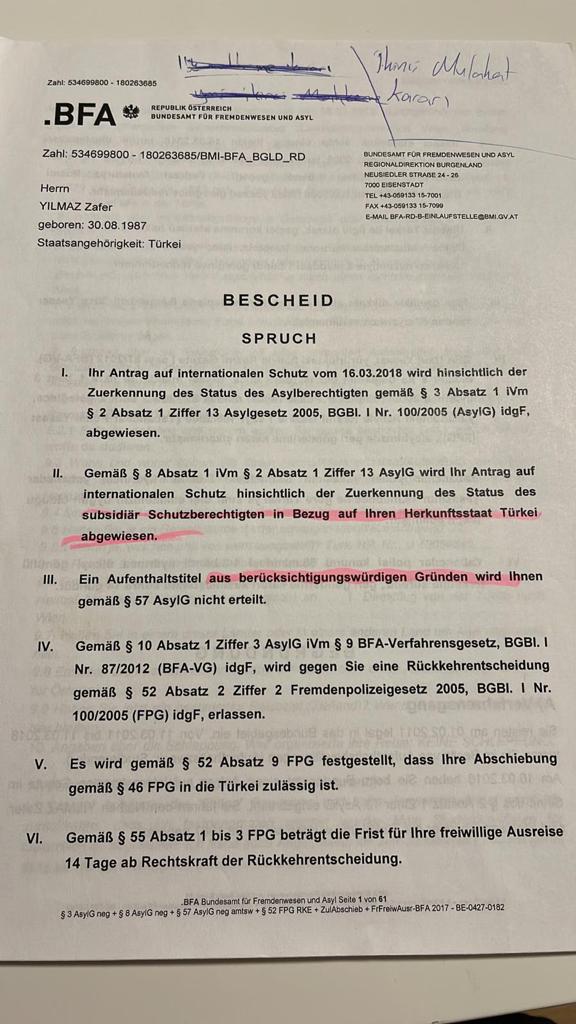

Zafer Yılmaz, 35, an editor for the Vienna-based Kronos news website who lived in Austria for almost 10 years and whose asylum application in Austria was previously rejected, was detained in Norway on April 15.

Yılmaz arrived in Norway to apply for asylum status a second time and to avoid deportation to Turkey. The Norwegian authorities stated that the decision of the Austrian court is binding on them due to Schengen rules, rejecting his application, Nordic Monitor has learned. He is now in custody, awaiting the conclusion of his appeal of the rejection of his application.

In 2018 Yılmaz applied for international protection and asylum in Vienna, where he first went to study at university 10 years ago, due to his affiliation with the Gülen movement, a group critical of the Turkish government.

Sources aware of the matter told Nordic Monitor that since Yılmaz has been living outside Turkey for a number of years, he could not submit official documents such as a search warrant or an arrest warrant issued for him. It is believed that the Austrian authorities assessed that there was no risk of arrest or mistreatment for him in Turkey. However, especially after an abortive coup in 2016, the Turkish government detained hundreds of thousands of people affiliated with the Gülen movement, which it claims was behind the coup attempt. According to data compiled from official statistics on terrorism convictions between 2015 and 2020 by Solidarity with OTHERS, a nongovernmental human rights organization based in Brussels, terrorism investigations were launched into 1,977,699 people by prosecutor’s offices all over Turkey.

After his asylum application was rejected twice by the local court, Yılmaz applied to the Austrian Constitutional Court on the grounds that his application was rejected due to procedural errors he made. However, the Constitutional Court declined his request since it did not fall within its jurisdiction. So the journalist faced the risk of being deported to Turkey and imprisoned, despite the fact that the European Court of Human Rights has ruled multiple times that the deportation of foreign citizens to countries where torture or ill-treatment is a genuine risk contravenes the European Convention on Human Rights.

Yılmaz claims that a time gap between the expiration of his residence permit and his asylum application caused a misunderstanding and that the Austrian authorities made an incorrect assessment. Stating that he went to Norway as a last resort in order to avoid deportation to Turkey, he has requested his documents meeting the asylum conditions be re-evaluated. Yılmaz’s lawyer is also trying to get him released. His colleagues worry that sending him back to Austria would mean that he is sent to Turkey since a decision was taken by the Austrian authorities to deport him to Turkey.

Yılmaz is among the founders of Free Journalists, a nongovernmental organization founded in Vienna in 2016 to support independent journalism and journalists in exile. Yılmaz is also an editor at Kronos, the publication arm of Free Journalists. Publishing in Turkish and German, Kronos is particularly interested in human rights violations and political issues in Turkey. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), access to the Kronos website has been banned 33 times by Turkish courts, indicating that Kronos is already on the black list of the Turkish government and the courts under its influence. The website also includes news stories of journalists fleeing Turkey to avoid arrest and ill-treatment. The fact that Yılmaz works for Kronos is sufficient reason for his arrest and mistreatment if he goes to Turkey.

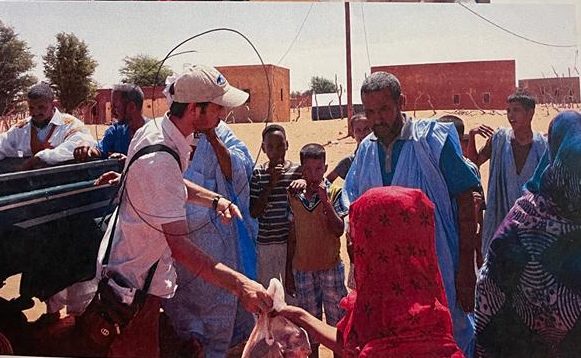

Yılmaz was a volunteer with the Kimse Yok Mu charity, which was banned by the Turkish government because of its affiliation with the Gülen movement. There are photographs showing Yılmaz taking part in the aid activities of the charity in Mauritania in 2013.

Kimse Yok Mu was set up in 2004 in Istanbul and had quickly developed internationally recognized relief programs in partnership with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The group was the only aid agency that held UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) special consultative status at the time.

It was active in 113 countries for years and developed the capacity to deliver emergency relief in disaster zones as well as to rebuild infrastructure in communities, thereby providing long-term assistance, which included the construction of homes, hospitals, schools and health facilities. However, it came under fire by the Turkish government when Erdoğan started attacking the Gülen movement. First, Kimse Yok Mu’s licenses to raise, hold and use funds for charitable work were suspended on September 22, 2014, and the charity was shut down in 2016. A large number of employees were jailed or faced arrest and prosecution on dubious charges. Many people were subsequently arrested simply because they made a donation to the charity group. Nordic Monitor previously published how donators were secretly profiled by Turkish intelligence.

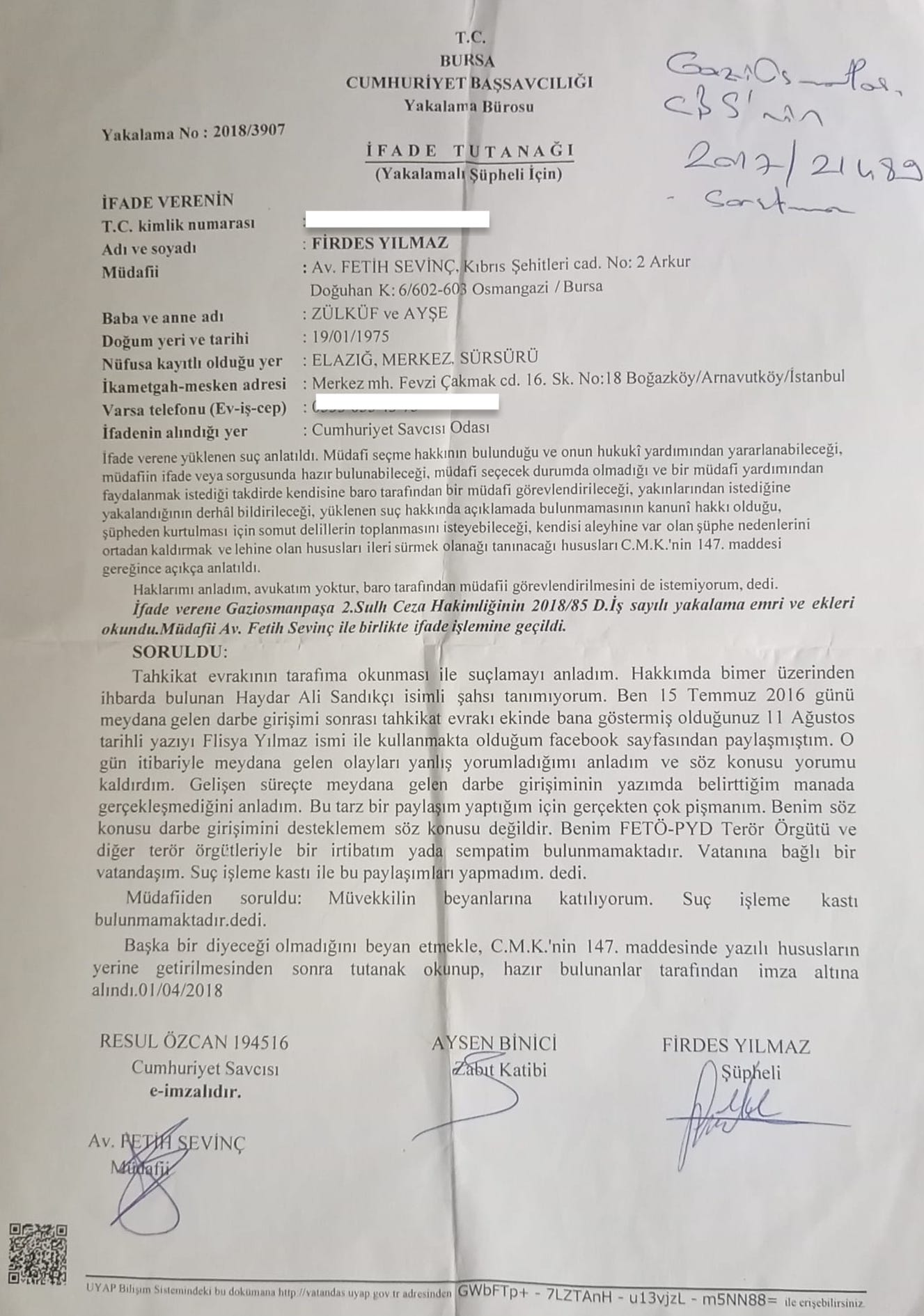

Another risky situation for Yılmaz is that an arrest warrant was issued for his sister in 2018 for alleged affiliation with the Gülen movement. For Turkish courts, a family member’s affiliation with the Gülen movement is sufficient reason to investigate and prosecute other family members. Many people in Turkey are still in prison because of their kinship relations.

Doğan Ertuğrul, the editor-in-chief of Kronos and a prominent journalist in exile, states that Yılmaz took part in the establishment of Kronos and also worked as the software, design and graphic editor of the website. He adds that Yılmaz assumed the responsibility of preserving Kronos’ writing and photographic archive and was writing stories on technology and lifestyle.

“Extradition of our colleague to Turkey means the risk of detention, imprisonment and ill-treatment. Therefore, he should definitely not be deported from Norway. I urge the Norwegian authorities and journalism and human rights organizations to consider this risk,” Ertuğrul says.

Levent Kenez, another journalist who fled Turkey, was recently at risk of being extradited to Turkey from Sweden. “If you are a journalist opposed to the government, getting arrested when you return home is something anyone in Turkey can easily predict today,” Kenez says.

According to Kenez, bringing government opponents from abroad to Turkey is a sign of success for Turkey’s diplomatic missions. He says he later learned that the extradition process initiated against him last year was a result of the insistence of the Turkish Embassy in Stockholm.

“I am sure that the Turkish Embassy in Oslo has been following Yılmaz’s case and will present it as a success if he is deported. They may even engage in a rivalry with the embassy in Vienna. They will present it as the Turkish government’s great victory in media outlets close to the government,” Kenez adds.

According to official reports, 118 people who are affiliated with the Gülen movement from 28 countries have been deported to Turkey. All of them were later arrested. Meanwhile, the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) does not process Turkey’s Red Notice requests because they are politically motivated.

In 2021 Nordic Monitor published secret Turkish Foreign Ministry documents revealing how Turkish diplomats collected information on the activities of critics in Norway, profiling their organizations and listing their names as if they were part of a terrorist organization.

An official document from the Directorate General for Consular Affairs at the Foreign Ministry dated October 21, 2016, confirms clandestine spying activity in Norway that has long been suspected. The document shows how critics who have been living in Norway for decades as well as those who have recently sought refuge to escape a massive crackdown in Turkey were spied on.

This week, Turkey was ranked 149th among 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) 2022 World Press Freedom Index, with the prominent press organization warning about rising authoritarianism in the country and declining media pluralism.

“Authoritarianism is gaining ground in Turkey, challenging media pluralism. All possible means are used to undermine critics,” said the press organization.