Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

The Turkish government released a convicted Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) fighter citing COVID-19 pandemic risks, allowing him to return to Syria to resume his activities on behalf of the terrorist organization.

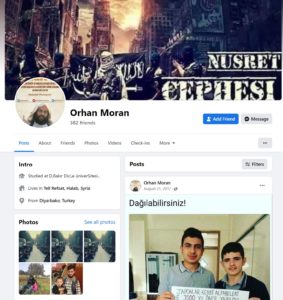

Orhan Moran, 32, has long been known as a jihadist to Turkish authorities and was shuffled through a criminal justice system that has proven to be lenient and forgiving when it comes to punishing dangerous jihadists from al-Qaeda and ISIS groups.

He fled Turkey in 2013 to escape a prison sentence following a conviction and went to Syria using smugglers who were allowed by the Turkish government to operate and traffic jihadists in the border areas. He helped recruit many from Turkey’s predominantly Kurdish province of Diyarbakır to the ranks of armed jihadist groups in Syria.

In his statement he said he had worked for a charity organization in Aleppo without naming it. His Facebook profile gives hints on what this organization might be. He frequently shared messages about the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (İnsan Hak ve Hürriyetleri ve İnsani Yardım Vakfı, or IHH), a Turkish charity that has helped both al-Qaeda and the ISIS in Syria.

He also sponsored the Jabhat Nusra-affiliated Öncü Nesil Humanitarian Relief Association (Öncü Nesil İnsani Yardım Derneği), whose members were investigated and arrested only to be released after intervention in the case by the Erdoğan government in Turkey. His profile picture features Nusra with a picture of Abdallah Muhammad Bin Sulayman Al-Muhaysini, an al-Qaeda cleric of Saudi origin who is among the leaders of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Syria.

Although he was wanted and faced an outstanding arrest warrant, Moran traveled between Turkey and Syria many times according to his own statement. On February 21, 2020 he turned himself in at the border and was arrested on charges of terrorism, more specifically over his links to HTS, also known as al-Qaeda in Syria. Turkish authorities let him go on February 15, 2022 citing pandemic risks. A month later, he went back to Syria to rejoin his jihadist comrades and connect with his Syrian wife and children.

On April 18, 2022 he was brought back to Turkey by Turkish intelligence agency MIT (Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı), and his detention was advertised in the pro-government press as a major sweep by MIT. He was alleged to be in preparation to attack Turkish troops stationed in the north of Syria. A picture of him in handcuffs and posing between Turkish flags was taken by the state news agency Anadolu and shared by many media outlets.

His detention appeared to be a public relations stunt by the agency, which has come under criticism for aiding and abetting various armed jihadist groups in Syria. The government news service praised the MIT operation and claimed Turkey has carried out numerous counterterrorism operations against ISIS in recent years.

Yet, Moran, who had been a fugitive for seven years between 2013 and 2020 and violated his conditional release in 2022, was quickly released after a brief detention in April, just like many jihadists who were simply reshuffled in the criminal justice system as part of the revolving door policy by the Islamist government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. His release was not covered by the Turkish media.

Moran’s case raised questions about how many ISIS, al-Qaeda and other dangerous jihadists were released by the Erdoğan government using the pandemic as an excuse. The government never announced figures on such inmates, but the government-endorsed bill in April 2020 allowed some 90,000 prisoners to go temporarily free in order to relieve Turkish prisons overcrowded with some 300,000 inmates during the pandemic.

The Erdoğan government categorically excluded political prisoners, journalists, lawyers and human rights activists from the release and kept them behind bars, prompting criticism from the opposition, the EU and the UN as well as an outcry from human rights organizations. The Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF) documented abuse in prisons during the pandemic era in its report, “Left Behind to Die: COVID-19 in Turkish Prisons and Discrimination Against Political Prisoners.”

The report lambasted the Erdoğan government for its discriminatory approach in reducing the prison population that benefited murderers and jihadists but excluded political prisoners.

The pandemic-related release has been renewed 12 times since it was first introduced in April 2020.

Among those released was notorious Turkish mafia boss Alaattin Çakıcı, known for his ties to Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and an ally of President Erdoğan. Çakıcı had been convicted of establishing and leading a criminal organization and committing a series of murders.

Thousands of militants, both Turkish and foreign, have used Turkish territory to cross into Syria with the help of smugglers in order to fight alongside ISIS groups there. Turkish intelligence agency MIT has facilitated their travel, with Kilis, a border province in Turkey’s Southeast, one of the main crossing points into ISIS-held territory. Human smugglers were known to have been active in the border area, although Turkish authorities often overlooked their trips in and out of Syria.

Turkish officials do not disclose the number of successful convictions in ISIS cases and decline to respond to parliamentary questions asking for such information. Instead, they often float figures on the number of detentions and arrests, which in many cases result in release and acquittal.

Erdoğan announced on October 10, 2019 that there were around 5,500 ISIS terrorists in Turkish prisons, of which half were foreign nationals. Yet on October 25, 2019 then-Justice Minister Abdülhamit Gül stated at a press conference that there were 1,163 ISIS arrestees and convicts in prison.