Levent Kenez/Stockholm

An Istanbul court on Monday convicted eight people, including philanthropist Osman Kavala, for their roles in anti-government protests in 2013. The defendants, accused of organizing a riot to overthrow the government, have been sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Many in Turkey think the verdict is unfair and that it is a political decision under pressure from the government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Apart from those convicted on Monday, there are other people who paid a price for the 2013 protests. These are state officials who opposed Erdoğan’s harsh and uncompromising stance against the protesters. They lost their jobs and later went to prison on terrorism charges.

Judge Rabia Başer, while working at the Istanbul 1st Administrative Court, canceled Erdoğan’s project to turn Gezi Park into a shopping center, a plan that had caused the protests to begin in the first place. The decision was later upheld by the Council of State. The Gezi Park protesters welcomed the decision and described it as a victory.

On July 17, 2016 a detention warrant was issued for Başer, who was among 2,745 judges and prosecutors suspended after a controversial coup attempt on July 15, 2016. Başer, who went to the courthouse and turned herself in, was arrested the same day. In 2018 she was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison for membership in a terrorist organization.

Since the abortive coup in 2016, the Turkish government has been regularly dismissing civil servants on accusations of membership in FETÖ, a derogatory term coined by the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to refer to the faith-based Gülen movement as a terrorist organization.

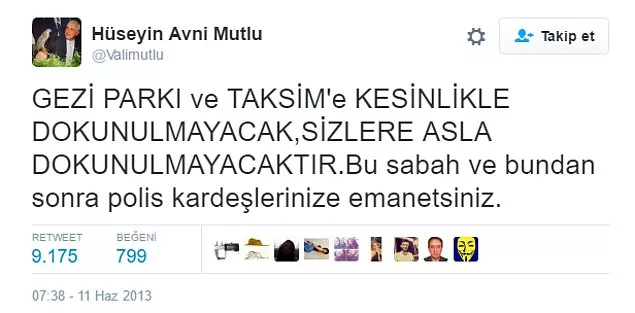

Another person who was victimized by the government is Hüseyin Mutlu, the governor of Istanbul at the time. Mutlu, who advocated ending the Gezi protests through negotiation, had met with the protesters a few times. The governor, who tried to ease the tension with social media messages, made an effort not to turn the police against the demonstrators and advised then-Interior Minister Muammer Güler not to intervene harshly with the crowds.

Mutlu was also among those arrested after the coup attempt on charges of attempting to overturn the constitutional order by force of arms and attempting to overthrow the government.

Mutlu was sentenced to three years, one month, 15 days in prison for the crime of “knowingly and willingly helping the organization without being a member of it.”

During the Gezi protests, one of the things Erdoğan frequently repeated was that protestors attacked and harassed a woman wearing a headscarf with a small child on June 1, 2013 in front of the Kabataş ferry pier near Gezi Park.

Zehra Develiğlu, the daughter-in-law of a ruling party mayor in İstanbul, said she was attacked by half-naked men and that they urinated on her, but no evidence could be found confirming the incident. Moreover, a CCTV video that emerged a month later revealed that Develioğlu had not been attacked at all and that she got into her husband’s car when he came to pick her up without incident. However, Erdoğan continued to claime that the Gezi protesters attacked headscarved women for a long time.

Ertan Erçıktı, the Istanbul public security branch manager at the time, was dismissed because he exposed the lie about the attack. He was later arrested for plotting against a pro-al-Qaeda terrorist organization called Tahshiye. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison in 2017.

Mesut Yılmaz, deputy director of the intelligence branch of the Istanbul Police Department, told Nordic Monitor that Şenol Kazancı, an advisor to then-Prime Minister Erdoğan who would later become head of the state-run Anadolu Agency, came to them and asked for a photograph or video of the alleged Kabataş attack. He said he told him there was no picture. “Despite this, Erdoğan didn’t hesitate to repeat the lie of a woman wearing a headscarf being attacked in Kabataş,” Yılmaz says.

Yılmaz recalls his department reported that the crowd gathered in Gezi Park had nothing to do with terrorism. Yılmaz states that thanks to the Istanbul police chiefs persuading the interior minister, people were able to gather in the park; the government had ordered from the very beginning of the protests that no one should be allowed in.

Yilmaz, who says they received instant information from the plainclothes policemen who stayed with the protesters in tents in the park, claims that the death toll would have been much higher had the İstanbul police chiefs not resisted the government.

Yılmaz thinks Kavala was convicted to intimidate Erdoğan’s opponents, sending the message that if anyone takes to the streets or does anything similar in the future, they will end up like Kavala.

Yılmaz, who was imprisoned for two years, is currently living in exile in the US. There is still a search warrant out for him. He thinks his colleagues Serdar Güldalı and Ahmet Öztürk, who are in prison, are being punished by the government for complying with the law.

Another Kabataş-like piece of propaganda spread by the government regarding Gezi Park was that activists who took shelter in a nearby mosque after the police fired tear gas had drunk beer there. Fuat Yıldırım, one of the officials at the mosque, said the young people did not drink alcohol in the mosque.

Yıldırım, who also said, “I’m a religious official, I cannot lie,” also revealed to the public the pressure he was under. A few months after the Gezi protests, Yıldırım was transferred to another place as punishment.

In an audio recording leaked to social media after the Gezi events, then-interior minister Güler told Cemal Kalyoncu, owner of the company that was to build the planned shopping mall, that he begged Prime Minister Erdoğan to allow the activists to read out a press statement but that Erdoğan ordered him to intervene aggressively with the demonstrators.