Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

A secret draft directive for the Turkish navy concerning warships transiting the strategic Bosporus and Dardanelles straits in times of peace and of crisis in accordance with the provisions of the 1936 Montreux Convention authorized the Turkish navy to block vessels before their entry into the straits.

According to the draft “Joint Air and Missile Defense Directive of the Turkish Armed Forces” (Türk Silahli Kuvvetleri Müşterek Hava ve Füze Savunma Yönergesi), which updated the rules of engagement in 2016, the Turkish navy was authorized to monitor warships passing through the Turkish straits and prevent violation of articles of the Montreux Convention, deny ships in violation entry to the straits in the first place and escort them out if they had managed to enter them.

The rules apply during peacetime and times of crisis in resorting to force by the Turkish Armed Forces and bring a number of restrictions to the actions of commanders and vessels in the field, in the air and on the sea.

For example, the directive requires commanders in the field to report every incident to their superiors in Ankara and to act according to orders given by the leadership in scenarios such as intercepting a warship or using force against a foreign vessel. It means Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will be calling the shots.

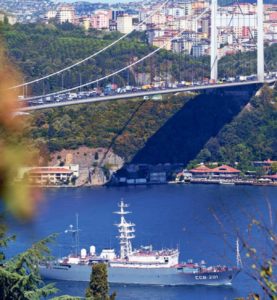

The cover and parts of the draft directive concerning the rules of engagement in the Turkish straits with respect to the Montreux Convention:

The 246-page directive, a copy of which was obtained by Nordic Monitor, lays out in detail the rules and regulations for the use of missiles and air defense elements by the Turkish armed forces in order to protect Turkish interests. It also covers the rules of engagement for violators of the Montreux Convention in the straits and in Turkish territorial waters. The update was ordered by Hulusi Akar, the then-chief of general staff and currently defense minister and replaced previously issued directives.

“Foreign warships that are found to be in violation of the rules of the Montreux Convention are blocked before entering the strait. After entering the strait, these vessels are accompanied or closely monitored during their passage when a situation is found to be contrary to the rules of the Montreux Convention,” the directive states.

The document makes clear that limitations on the rules of engagement in the straits would be lifted for states that are at war with each other, suggesting that the Turkish navy would have a freer hand in acting against Russian and Ukrainian warships that transit the straits. The rules of engagement would remain in effect for non-warring parties according to the secret directive, which means that Turkey could chose to allow NATO allies or others that want to send military aid to Ukraine through the straits.

The directive explicitly makes reference to the Montreux Convention as well as international law, saying that the rules of engagement would not be in violation of such agreements that are binding on Turkey.

Against the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Turkey has so far remained ambiguous on how to enforce the rules for transiting warships other than stating that it would exercise its rights under the Montreux Convention. Although Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu described the Russian military operations in Ukraine as a war on February 27 during an interview with CNN Türk, Turkish officials including President Erdoğan have been reserved in their speeches.

On February 28, 2022 President Erdogan said Turkey would implement a provision of Montreux in a way to de-escalate the crisis. “We have decided to use the authority given to our country by the Montreux Convention regarding the ship traffic in the straits in a way that will prevent an escalation of the crisis,” Erdoğan said, adding to that Turkey would not sever its ties with either Russia or Ukraine. He criticized NATO allies for not doing enough while noting that Turkey would fulfill its obligations as an ally.

The double talk coming from Turkish leadership means only one thing. The ruling Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) government hopes to weather the crisis with minimal adverse impacts amid growing difficulties in the domestic economy, increased pressure from the political opposition and heavy reliance on Russian gas and tourism revenue. Erdoğan also fears that Russia may press harder in Syria’s Idlib province and intensify military operations against Turkish-backed opposition groups, prompting a new refugee wave towards Turkey.

Unlike its NATO allies, Turkey also did not close its airspace to Russian aircraft and shied away from joining any punitive economic measures and sanctions on Russia.

Ankara most likely has no intention of fully enforcing the Montreux provisions that could invite the wrath of Moscow. The rules of engagement would provide significant leeway for President Erdoğan on how to implement the provisions.

Text of the 1936 Montreux Convention:

The rules of engagement on the sea explicitly state in section 7 that “the rules of maritime engagement in the form of deterrent and coercive measures such as boat/ship sinking, firing, harassment and similar engagements that can create political impact and/or consequences are put into effect with the permission of the Chief of General Staff in accordance with the authority given by the Prime Minister.”

In other words, only Erdoğan — who abolished the prime ministerial position in 2017 when Turkey switched to a presidential system of governance from a parliamentary democracy – can order the firing, sinking or harassment of foreign warships in the Turkish straits.

The directive reflects Turkey’s long-standing position to avoid any conflict over the Montreux Convention and to keep peace in the Black Sea. Ankara has since the beginning of the 2000s opposed US pressure to allow a new and permanent NATO force in the Black Sea, fearing that it would violate the convention and complicate relations with Russia.

Turkey’s balancing act between the US, its long-time NATO ally, and Russia, its neighbor and trading partner, has become more complicated in recent years, especially with a massive purge of pro-NATO officers from the Turkish military in the aftermath of a false flag coup attempt in July 2016.

The fact that Erdoğan has consolidated so much power in his hands and tightened his grip on the army, intelligence, parliament and judiciary is also a cause for concern for many Turkey observers. Acting on the whims of one man, Turkey has in the past found itself in hot water with both Russia and its NATO allies.

A change in the rules of engagement with respect to Syria led to the shooting down of a Russian Sukhoi Su-24M on November 24, 2015 by a Turkish F-16 fighter jet near the border with Syria, close to where Turkey’s Hatay and Syria’s Latakia provinces meet in mountainous terrain. Nordic Monitor previously published documents showing that President Erdoğan instructed the Turkish Air Force to shoot down a military aircraft and that the order was executed by Akar, who personally congratulated the pilot who took the shot.

The downing of the Russian jet caused a diplomatic row between the two countries, with Russian President Vladimir Putin calling it “a stab in the back,” until Moscow and Ankara agreed to restore relations in June 2016. Although Erdoğan and other Turkish leaders had initially defied Russian threats and vowed to act again in line with the rules of engagement if another violation were to take place in the air, they later toned down the rhetoric.

On the other hand, an array of problems emerged between Turkey and the US after Ankara’s purchase of S-400 long range missiles from Russia, a divergence on policies with respect to Syria and the Erdoğan government’s help to Iran in circumventing US sanctions. Turkey was expelled from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program and was subjected to sanctions and restrictions.

The Montreux Convention was signed on July 20, 1936 by Turkey, Bulgaria, France, the UK, Australia, Greece, Japan, Romania, the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. During peacetime, light surface vessels (defined as warships displacing more than 100 tons but not above 10,000 tons) of all powers may transit the straits after giving prior notice to Turkey as required by the convention. Turkey may waive the notification requirement if the warships are transiting for the purpose of providing humanitarian assistance.

The convention applies specific individual and aggregate tonnage and numbers limits. These limitations effectively preclude the transit of capital ships and submarines of non-Black Sea powers through the straits, unless exempted under Article 17. Article 17 of the convention permits a naval force of any tonnage or composition to pay a courtesy visit of limited duration to ports in the straits at the invitation of the Turkish government. In such instances, the tonnage and numbers limitations of the convention do not apply. Warships of non-Black Sea powers may not remain in the Black Sea for longer than 21 days.

Despite being the subject of much discussion since it entered into force, the Montreux Convention has survived major crises, including World War II, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact and Russian conflicts with Ukraine and Georgia.

The implementation of the agreement is the responsibility of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Standard operating procedure foresees that notification of warships intending to transit the Turkish straits be made initially with the Turkish Foreign Ministry, which in turn passes the request to the General Staff and that the request be assessed by the Naval Command, which shares the notification with the relevant branches within the Joint Address Indicator Group code named MAGG-7063, military units that have a mandate to monitor passing warships.

A copy of the notification is also sent to the Signal Intelligence Directorate (MIT Sinyal İstihbaratı Başkanlığı, SINISTHBSK) in Ankara, which is run by the National Intelligence Organization (MIT).