Levent Kenez/Stockholm

The judge representing Turkey on the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), Saadet Yüksel, continues to stand apart from the majority in human rights cases related to Turkey. Expressing dissenting or partly concurring opinions on almost every decision, Yüksel addresses the politicized Turkish courts, even in cases in which she makes the same decision as the majority but argues that there is a lack of communication between the ECtHR and Turkey’s Constitutional Court. In the applications made after a controversial coup attempt on July 15, 2016, which led to a proliferation of major human rights violations in Turkey, she takes a position in favor of the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan government.

Nordic Monitor previously reviewed the cases in which Yüksel dissented from majority opinions in which the applicants were political critics of President Erdoğan, taking an explicit stance in line with local Turkish courts. Among these applicants were Selahattin Demirtaş, the former co-chairman of a pro-Kurdish opposition party, businessman Osman Kavala and journalists Kadri Gürsel and Ahmet Şık.

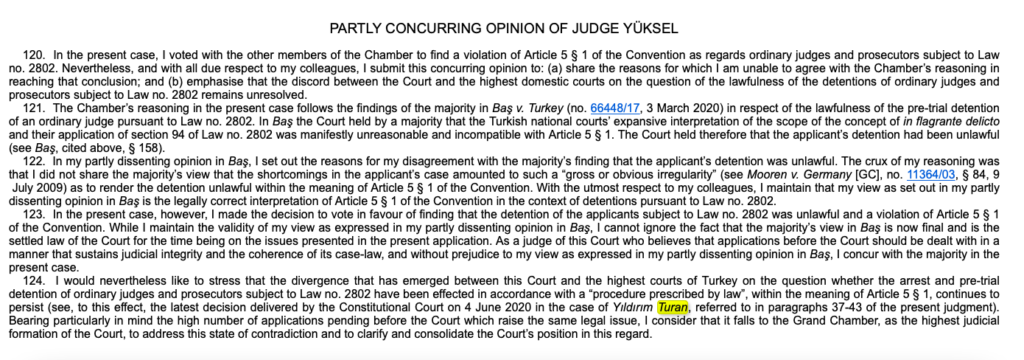

In November 2021 the ECtHR condemned Turkey for the arrest of 427 judges and prosecutors in the days following the failed coup and ruled that the arrests were carried out through procedures that violated the European Convention on Human Rights. It ordered the Turkish government to pay 5,000 euros to each applicant. Referring to a previous decision of the court, Yüksel stated that she complied with the majority because it constituted case law but stated that she did not agree that the rights of the applicants had been violated. She also expressed disagreement between the court and the highest courts in Turkey regarding “compliance with the procedure prescribed by law.”

Human rights defenders frequently criticize the Turkish Constitutional Court, arguing that journalists in particular are victims of decisions made by members who are sympathetic to Erdoğan. The Constitutional Court previously ruled that decree-laws enacted during a state of emergency imposed by the government following the coup attempt in 2016 are binding and that some fundamental rights may be suspended in exceptional circumstances. Yüksel frequently refers to the Constitutional Court, arguing that domestic remedies have not been exhausted and lends credibility to the Constitutional Court.

Last December the ECtHR ruled that Turkey had violated the fundamental rights of well-known journalist Nazlı Ilıcak, who was detained on July 26, 2016 and arrested on July 29, and ordered the country to pay damages to her. The only judge who did not agree with the decision was Yüksel. In her partly dissenting opinion on the ruling, Yüksel wrote that the pretrial detention imposed on Ilıcak was justified under Article 5 § 1. Contrary to her colleagues, Yüksel agreed with the domestic authorities, who had “plausible reasons” for suspecting Ilıcak of having committed offenses that required pretrial detention.

On Tuesday the ECtHR ruled that Turkish-German journalist Deniz Yücel’s pre-trial detention in 2017 violated his rights — the right to liberty and security and the right to compensation for unlawful detention — as well as his right to freedom of expression. The court ordered Ankara to pay Yücel damages in the amount of €12,300.

Yüksel also opposed this decision on the grounds that Yücel had applied to the Turkish Constitutional Court, which ruled that Yücel’s security and freedom of expression were violated in 2019. Claiming that Yücel is no longer a victim, Yüksel also criticized the ECtHR’s finding that the Constitutional Court’s compensation was low. In its decision the ECtHR examined whether Yücel was no longer a victim and argued that Yücel’s application to the ECtHR was different from the one made to the Constitutional Court.

Following Yüksel’s appointment to the top court, Human rights observers expressed concern about her impartiality given the close relations between her and Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Not only was her brother Cüneyt a former AKP lawmaker and deputy chairman, but Yüksel herself was affiliated with Islamist foundations supported by the Erdoğan government. She was also an assistant to and student of the late Burhan Kuzu, a chief aide and leading propagandist of President Erdoğan. Nordic Monitor previously published a report on Yüksel’s strong ties to the government.

Meanwhile, ECtHR President Róbert Ragnar Spanó said at a press conference on Tuesday the court had received 15,250 applications from Turkey in 2021, an increase of 30 percent over the previous year. When asked why the applications of journalists Hidayet Karaca and Mehmet Baransu, who have been imprisoned in Turkey for almost seven years, have not yet been examined, he cited the court’s insufficient resources as the reason.

Yüksel and Spanó were at the center of harsh criticism in September 2020. Spanó was the first ECtHR president to pay an official visit to Turkey, the government of which is a party to more than 16 percent of the cases before the Strasbourg court. Spanó and Yüksel met with President Erdoğan behind closed doors at his presidential palace.

Those who expected Spanó to give a strong message to top officials that Turkey must implement European court judgments and respect the rule of law were disappointed. Spanó made courtesy calls and received an honorary doctorate from Istanbul University, which has fired scores of academics in a massive crackdown since 2016, at a ceremony that students and journalists were not allowed to attend, at Spanó’s request. Spanó also went to Yüksel’s hometown of Mardin, a city in southeastern Turkey

French daily Le Monde claimed that Yüksel and Spanó are close friends, implying that their relationship is more emotional than professional.