Levent Kenez /Stockholm

The Turkish Justice Ministry in its periodic peer-reviewed journal censored scores of academic articles and papers written by judges and prosecutors who were dismissed or imprisoned as part of a witch-hunt following an abortive coup in 2016, a Nordic Monitor study has revealed.

The Journal of Justice (Adalet Dergisi), which has been published since 1873 by the Justice Ministry, aims to contribute to the judiciary with academic works and support the academic evaluation of the legal policies implemented by the ministry, according to its official website. The journal, which is published twice a year in Turkish, mostly includes articles by ministry personnel. Each issue contains 15 to 20 articles, some of which are also published in English.

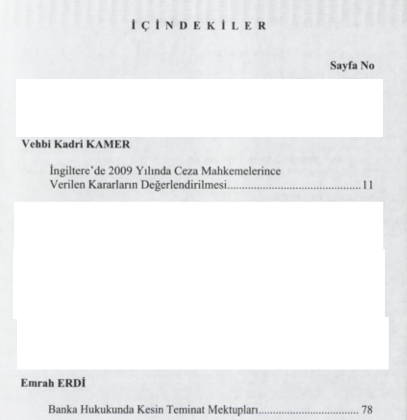

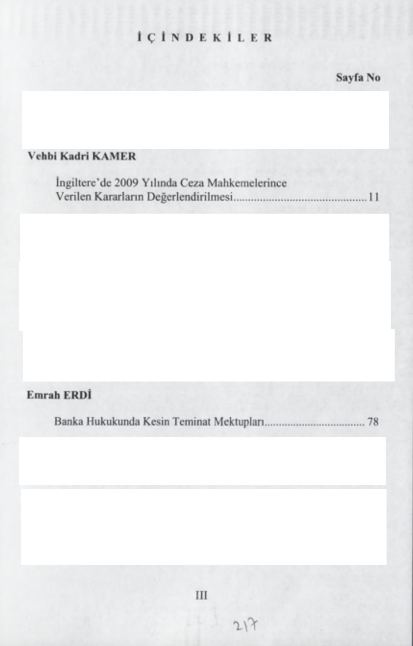

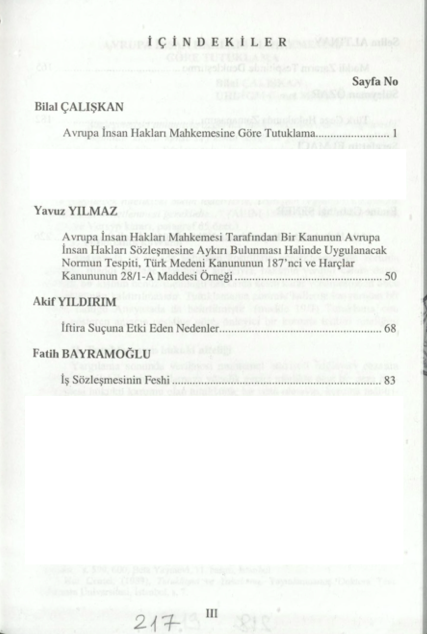

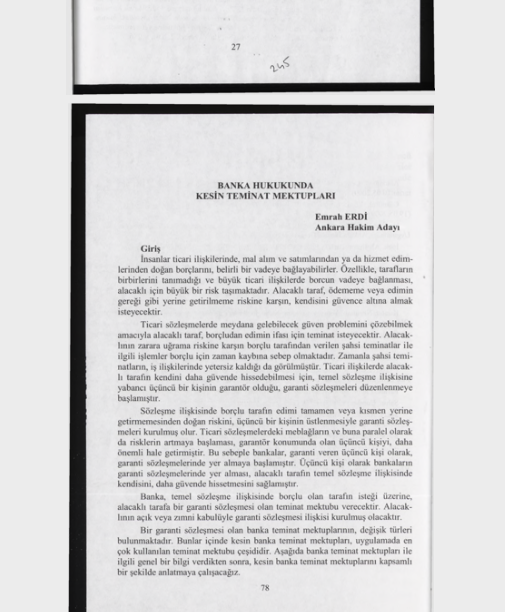

An examination of the journal archives on its website reveals that some articles published before 2016 were removed. The titles were covered with white strips in the table of contents. It appears to have been censored quite amateurishly, as the hard copies of the journals were converted to PDFs. It seems the ministry did not feel the need to redesign it digitally.

For instance, in the 40th issue published in May 2011, the content of only six articles can be accessed digitally. Interestingly, page 27 of the journal is followed by page 78. Likewise, in the 48th issue published in January 2014, the 82nd page comes after the article that ends on the 25th page.

Considering that the censored articles cover 2016 and earlier, it appears they were removed from the archive because they were written by judges and prosecutors who were purged, regardless of content.

In the aftermath of the coup attempt, 4,560 judges and prosecutors were dismissed and replaced by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan loyalists, many of whom were barely out of college and others who were politicians in the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). A total of 2,431 of the judges and prosecutors were detained on trumped-up charges. Some 30 percent of Turkey’s judges and state prosecutors were dismissed and/or jailed, part of a sweeping crackdown that has seen more than 130,000 people sacked or suspended from the military, police and civil service.

Among the members of the judiciary who were imprisoned, those who tried cases that angered the government was put in solitary cells. For example, during the Gezi Park protests of 2013, Judge Rabia Başer, who canceled the government’s project to transform the park into a shopping mall, and her husband Mustafa Başer, who ruled to release a number of imprisoned journalists in 2015, a judgment that was not enforced by the government, have been in solitary cells in different cities for 63 months. They have never seen each other during this period of time. When they were first jailed, they were forbidden to even exchange letters as part of state of emergency prohibitions implemented immediately after the coup attempt.

Members of the judiciary who lost their jobs but were not imprisoned were not able to become lawyers as a result of government pressure although there is no legal obstacle barring their way. They were not even hired by private companies due to the fear of the government. Stories of judges and prosecutors who work in menial jobs are frequently shared on social media.

Meanwhile, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) last week condemned the arrest of 427 judges and prosecutors after the failed 2016 coup attempt. The Strasbourg court considered that the arrests were carried out through procedures that violated the statute that protects representatives of justice and that therefore the Turkish state will have to pay 5,000 euros in compensation to each of those affected, most of whom are in prison.

Legal experts claim that although the decision referred specifically to members of the judiciary, it concerns all civil servants who lost their jobs, showing that they are in the right according to the norms of universal law, even if they can’t get satisfaction in local courts. The Turkish Constitutional Court currently cannot make a decision on dismissed civil servants that challenges the government’s rhetoric labeling them as terrorists.