Abdullah Bozkurt / Stockholm

Turkish authorities disclosed the phone records of slain Russian ambassador Andrei Karlov, revealing the Russian envoy’s contacts in Turkey and abroad, a move that may invite the wrath of Moscow.

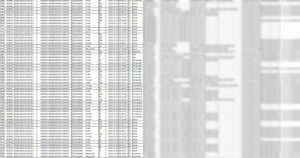

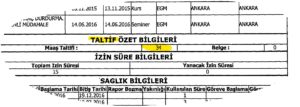

Karlov’s phone and SMS text messaging records totaling 3,317 items since January 1, 2015 until the day he was assassinated, December 19, 2016, by a Turkish police officer were fully incorporated into the murder case file in a deliberate act by prosecutor Adem Akıncı, who could instead have sealed them after review in lieu of an investigation.

The phone records, reviewed by Nordic Monitor, show the Russian ambassador’s daily routine, whom he talked with while representing his country’s interests in Turkey and what numbers he frequently called.

None had anything to do with the assassination, and there was no hint that might have shed light on the murder that was committed by 22-year-old police officer Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş, who was rewarded multiple times with bonuses for his services by the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

It begs the question of why the prosecutor decided to reveal all the ambassador’s contacts within the two-year time frame when he could have deemed the evidence confidential and gotten it sealed by a judge. Instead he opted to make it part of the public record.

Akıncı was specially selected by the Erdoğan government to lead the investigation. He was ordered to sabotage the probe by obscuring the evidence that pointed to radical pro-government groups that had links to the regime. None of the imams, some of whom were on the government payroll, who played a role in radicalizing the assassin were investigated as accomplices by Akıncı.

The prosecutor denied several requests filed by Russian investigators and embassy officials during the course of the investigation despite being urged otherwise by the foreign ministry desk that handles Russia. In one case the Russian government sought a lie detector test for a key suspect whom Turkey claimed to be complicit in the assassination of the ambassador. Although the suspect agreed and waived his privacy rights, Akıncı refused to more forward with the Russian request.

On another occasion Turkey rejected the Russian government’s urgent request not to conduct an autopsy on the body of the slain ambassador. The note sent by the Russian Embassy in Ankara stated that the ambassador’s grieving widow, Marina Mihaylovna Karlova, married to him for 45 years, did not want a Turkish medical examiner to perform the autopsy on her husband’s body, signaling that the Russian government wanted to keep the body intact and take the first look at it as part of its own investigation.

Turkish intelligence agency MIT also helped the prosecutor set up a false suspect to deceive a Russian delegation that was scheduled to visit Turkey for a fact-finding mission. The revelations about the plot were made in a court hearing on September 4, 2020 by a victim who was abducted and tortured by MIT.

It was clear that the Erdoğan government set up the investigation and ensuing trial to be derailed from the start. The Turkish prosecutor ignored all leads to pro-government groups; did not indict any radical figures who had been in contact with the assassin in the months leading up to the assassination; and deliberately deflected the focus of the probe away from people close to the Erdoğan government. Instead, the government-critical Gülen movement and others were scapegoated with no real evidence presented by the prosecutor to support the allegations.

There are a number of pieces of evidence in the case file that show the killer was in fact radicalized by jihadist literature, attended prayer circles organized by pro-government jihadist cleric Nurettin Yıldız and had been befriended by known al-Qaeda militants. However, the government did not pursue the leads into jihadist networks and did not investigate the al-Qaeda figures who had worked with the killer. It was also revealed that the Erdoğan government had given the killer 34 bonuses in two years’ time.

The trial concluded in March 2021 with the conviction of the scapegoats. The real culprits who helped the assassin radicalize remain free with the help of the Turkish government. Russian authorities conducted their own investigation into the incident and asked that a copy of the case file be forwarded to the Russian prosecutor’s office. Russian observers followed the trial proceedings, and Russian delegations went to Turkey several times to meet with the Turkish authorities who had investigated and prosecuted the case.

Akıncı was a low-profile prosecutor in the town of Kuşadası until the Erdoğan government decided to bring him to the capital city of Ankara on June 2016, and handed him the case files involving critics and opponents of the Erdoğan regime. His taking over the investigation into Karlov’s assassination was surprising given his lack of experience and credentials in prosecuting complex cases that have international repercussions.

For his services in legal cases in which the government intervened to secure the desired outcome, Akıncı’s position was upgraded in April 2019.

In the meantime, Russia’s own investigation into the murder is still underway.