Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

An operative of Turkish intelligence agency MIT who ran covert operations in southeastern Europe and organized rallies in front of foreign embassies in Ankara turned out to have played a key role in a false flag coup bid in 2016, court documents have revealed.

Ercan Şen, a Turkish official, returned to Turkey from Bosnia and Herzegovina, where he had spent two weeks running clandestine operations on behalf of the spy agency, just in time to take up his position around the Gendarmerie General Command headquarters. His job was to lead a mob towards the headquarters, which was already on edge over a possible terrorist threat and had beefed up security in and around its perimeter.

Staff at the headquarters thought they had come under attack as predicted by intelligence picked up days before the coup attempt on July 15, 2016, which turned out to be a false flag plotted by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his military and intelligence chiefs to launch an unprecedented purge from the military, police, gendarmerie and other government branches.

Şen is one of those rare people to have admitted on the record that they knew about the coup bid long before it took place. In fact, before the Turkish president and other government officials started accusing opposition group the Gülen movement of complicity in the attempt, he told the court he knew Gülenists were behind it and confirmed this when he called a journalist friend of his living in Germany. The movement’s leader, Fethullah Gülen, denied the government accusations, and the Erdoğan government has failed to present evidence linking the movement to the abortive putsch.

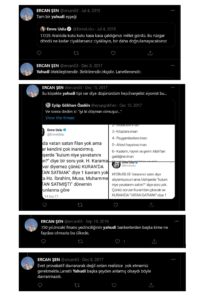

Ercan Şen’s testimony during cross-examination:

Nordic Monitor identified several other MIT agents who played critical roles in framing generals in the military mobilization that appeared to be very limited in number and confined to only a few cities. Sadık Üstün, a MIT operative who played a key role in organizing Islamist groups in Libya in 2011 and later returned to Turkey to run political operations on behalf of President Erdoğan, was the first agent who inadvertently exposed the false flag.

Üstün, a military man-turned-spy, prematurely named a decorated general, senior member of the Supreme Military Council (YAŞ) and former Air Forces Commander Akın Öztürk, as the leader of the putschists when the general was still at his daughter’s home, located some four or five kilometers from Akıncı Air Base, the alleged headquarters of the putschists. Öztürk, who had no affiliation with the Gülen movement, was completely unaware of the plot and was playing with his grandchildren on the night of the coup attempt.

Şen appears to be another MIT agent who made a mistake when he listed himself as a plaintiff in a coup trial and was forced to take the stand for cross-examination. Appearing as a witness at the Ankara 23rd High Criminal Court hearing on December 10, 2018, Şen said he drove 3,000 kilometers from Bosnia to arrive in Ankara on July 15, accompanied by Bosnians.

He arrived in the vicinity of the presidential palace and gendarmerie headquarters and started organizing people and blocking the road around the time some troops were mobilized to respond to the possible a terrorist attack. He said an associate named Irfan who works in Skopje, Macedonia, had given him some 300 Turkish flags and that he had distributed most of them to be used in pro-Turkey demonstrations in Bosnia. He still had some 30 or 40 flags left in his car and took them to Turkey, suggesting that everything was planned in advance.

He claimed he was injured with a bullet to the ankle and visited a hospital before returning home. But he did not stay there and later joined the rally in front of General Staff headquarters, egging on the mob gathered there as well as leading them in raiding the headquarters, which prompted warning shots from special forces deployed to protect the General Staff.

Ercan Şen’s motion through his lawyer to participate the coup trial as a plaintiff:

He admitted that he worked for the government but claimed his activities in Bosnia and during the coup attempt were civil activism. When asked directly whether he worked for MIT, Şen’s response was evasive. He said there was nothing wrong with working for the intelligence agency but claimed he was in a senior position at the Ministry of Education without elaborating on what that position entailed.

The defense asked how he was able to use a high-powered, military grade G-3 rifle when he was working for the Education Ministry. Şen did not respond.

Col. Şükrü Demirtürk’s PowerPoint presentation in court, highlighting the role played by Ercan Şen in the coup attempt:

In a hearing on February 13, 2020, Col. Şükrü Demirtürk referred to Şen’s testimony to make the point that Şen’s actions did not appear to be random, but rather planned.

“The fact that the plaintiff Ercan Sen put 30-40 Turkish flags in the trunk of his vehicle, brought them all the way from Bosnia to Turkey, left them in there when he unloaded his luggage at home in Ankara and later brought them to Beştepe [where gendarmerie headquarters and the presidential palace are located] is inexplicably contrary to the normal course of life,” Demirtürk said.

Lt. Col. Erdoğan Çiçek was another defendant who questioned Şen’s movements on July 15 and cast doubt on his statements. He also raised the possibility of Şen’s employment at the spy agency and his training in the use of a high-powered, military grade rifle. Defendant Bülent Ak asked him why he called his friend all the way in Germany to understand what was going on in Turkey. Şen simply said he was a knowledgeable person and did not disclose his friend’s identity.

Lt. Col. Tuncay Koçak, head of the organized crime unit at the Gendarmerie General Command, testified that Şen was a MIT agent:

According to Lt. Col. Tuncay Koçak, head of the organized crime unit at the Gendarmerie General Command, Şen was a MIT agent. Speaking during a hearing at the Ankara 23rd High Criminal Court on February 10, 2020, Koçak said even the presiding judge understood Şen was a MIT agent and asked about his duties. He raised the possibility that Şen might have brought some foreign fighters from Bosnia and Herzegovina to the front of the headquarters.

Şen is one of the founders of the Bosna Dayanışma Grubu (Bosna Solidarity Group), a cover that helped him and his associates move around southeastern Europe. His group trafficked not only arms and supplies but also fighters to the Balkans during the Bosnian War in the 1990s. His current public position is at the Ministry of Education’s General Directorate of Support Services, where he is officially head of publications and educational tools.

He published American author Grace Halsell’s book “Forcing God’s Hand” in Turkish, which was widely distributed among Islamist circles in Turkey with the help of Necmettin Erbakan, the founder of political Islam in Turkey and mentor to Turkish President Erdoğan. The book, which talked about a marriage of convenience between the US Christian right and Israel, was presented in Turkey as part of an anti-Christian and anti-Semitic campaign that was discreetly endorsed by Turkey’s National Security Council (MGK).

His tweets portray him as a staunchly anti-Semitic figure who called for wiping out the Jews and described Jews as a damned race. He called critical journalist Emre Uslu, who lives in the US, a “dog-faced Jew.”

Some of the protest rallies held in front of foreign embassies in Ankara bore the signature of Şen and his Bosnian group.

Major evidence confirming that the putschist attempt was in fact a false flag operation is found in a document that listed the events that took place in the early hours of July 16 before they actually occurred, suggesting that the intelligence agency had planned several incidents to make the coup attempt appear real.

According to an official document written by Ankara public prosecutor Serdar Coşkun, who drafted indictments in the coup trials, the events that transpired that night were known by Turkish authorities in advance. The document was dated July 16 and time-stamped at 1 a.m., three hours after the coup attempt began to unfold. Yet, the document mentioned events that took place after 1 a.m., which can only confirm that those events were actually planned in advance by operatives of the Erdoğan government, not the putschists. It also laid bare the fact that MIT wanted more bloodshed in the chaotic events.

For instance, the document mentioned the bombing of the Turkish Parliament by warplanes and stated that people were killed. In reality there were two explosions in the parliament, one at 2:35 a.m. and a second at 3:24 a.m. Nobody was killed, and it was not entirely clear that the explosions were actually caused by bombs dropped from a plane. The damage suggested that explosives planted on the site were used to blow up sections of parliament.

Another prediction made by prosecutor Coşkun was the raid on some private TV stations by the putschists, but no name was mentioned. On the night of the coup, it was only the Doğan Media Center, which hosts the CNN Türk and Kanal D TV stations and the Hürriyet newspaper, that was raided by pro-coup military troops. The raid on the Doğan Media Center took place at 3:10 a.m., two hours after the paper was written. As mentioned earlier, it was the same media outlet where President Erdoğan appeared for the first time to make a speech to the nation and Hande Fırat, the Turkish intelligence asset, interviewed him.

Official document written by Ankara public prosecutor Serdar Coşkun at 1:00 a.m. listed events that happened after the document was written or events that never took place, suggesting that coup incidents were planned by Turkish authorities far in advance:

The document predicted the bombing of the presidential palace five hours before an explosion took place near the palace. The alleged perpetrators who had state-of-the-art F-16 warplanes miraculously missed the huge presidential complex in a national park and hit only a car park and overpass near the complex. These incidents took place at 6:19 a.m. In other words, not only was the timing wrong but also the description of the incident and the targets were not accurate.

What is more, the document claimed that the presidential palace was besieged by putschists who wanted to storm the building and take it over. Yet, it was later uncovered that only 13 officers, three of whom were high-ranking, and 10 privates went to the palace, where hundreds of security personnel were stationed.

There was also a claim that noise-generating bombs were dropped in Ankara by jets when no such action took place. The noise was generated by a sonic boom from jets that flew at high speed and low altitude. Some incidents mentioned in the document never took place on the night of the coup. For example, the document talked about a siege of MİT headquarters in Ankara and the bombing of the Special Forces Command and the Security Directorate’s intelligence unit by pro-coup soldiers. The appointment of new officers as chief of general staff and force commanders by the putschists, which were mentioned in the document, never happened.

At a time when no evidence had been collected and the incidents were still in progress, the document named Turkish Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen, who has been living in the US since 1999, as the mastermind of the coup.

This document and allegations in it were used as evidence to issue warrants for hundreds of generals, admirals and colonels as well as civilians. It was also presented as evidence in the arrest of thousands of judges, prosecutors, journalists and others. It is clear that the plot by Turkish intelligence was prepared in advance and that the plotters recorded events that either did not take place or happened hours after the key document was generated. The planned events also indicated that the plotters wanted to spark outrage in Turkish society, and that is why they picked targets like parliament, which did not make an sense for alleged coup perpetrators who would instead want to keep public opinion on their side in the post-coup period.

In the end Erdoğan got what he wanted. He consolidated power in his hands, switched the country’s parliamentary regime to an imperial presidency, eliminated generals and admirals who opposed his cross-border military adventures, persecuted the opposition, jailed tens of thousands who had nothing to do with the coup and shut down nearly 200 media outlets.