Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Abdulhamit Özmen, a 31-year-old sergeant who had worked as a computer expert and systems information manager for the gendarmerie, revealed details of of torture and abuse at the hands of the police in Turkey.

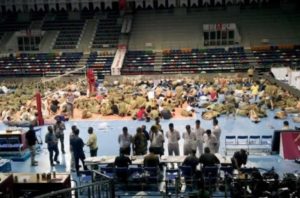

According to court documents obtained by Nordic Monitor, Özmen described what he called an apocalyptic scene at a sports hall that was turned into an unofficial detention site where detainees were tortured for days and weeks with no access to lawyers or family members as well as medical treatment.

His testimony was delivered during a hearing on November 10, 2019 at the Ankara 23rd High Criminal Court. He said police were trying to beat the detainees to death and denied them food, water and bathroom visits and that he had seen several lifeless bodies on the ground, apparently tortured to death. His account corroborates testimony delivered by dozens of other detainees who were squeezed like sardines into the sports hall.

In his initial testimony on April 17, 2018 Özmen came to court with a prepared statement that he wrote, detailing the torture and abuse he sustained during detention. But when he took the stand, he could not read it out loud, apparently as a result of the trauma he had suffered, and said he could not talk about the sexual abuse. Instead he said would later submit written documents. He talked about the torture in general terms and recanted a statement that was forced on him by the police under torture.

Özmen, who has bachelor’s degree in computer science, had been in the gendarmerie for only 10 months when a false flag coup bid took place on the night of July 15, 2016. He was a rookie but was trusted by his commanders, who tasked him with keeping the computers functioning at headquarters.

Court testimony of Abdulhamit Özmen reveals details of the torture he suffered at the hands of police and intelligence officers:

For him it was a normal day, and he was working late at Gendarmerie General Command headquarters, fixing computers as he had done many times under orders from his superiors. In the evening he and many others in the building were told that there could be a terrorist or even a cyber attack on the headquarters and was instructed to remain vigilant and take the necessary security measures.

When the building came under fire by unknown parties, he did not know what to do. He had no training in what to do under attack and followed others who had gathered in halls on the upper floors to protect themselves from the hail of bullets that was raining down on the building and breaking windows.

He called the police emergency line twice and was told to stay in a safe place until things calmed down. In the early morning hours of July 16, he was happy to see the police had arrived. It turned out that special police force teams, many in civilian clothes, were deployed by the government to take over the headquarters from the alleged putschists. Police snipers started shooting at the building from nearby residential buildings with no advance warning.

While many were detained and subjected to immediate torture and beatings at the site, he was one of the lucky ones. He said he was a computer guy, had nothing to with any incident and was eventually told to go home.

His freedom did not last long, however. The next day he was called to report for duty, and he went to headquarters on Sunday to continue working on computers. Then he was called to the backyard, singled out from the rest, handcuffed and placed in detention. When he was handed over to the police and on the way to the Ankara Police Department building, he knew things would get bad.

When they arrived at the building, a police officer dragged him by the arm and started punching him in the face and head as he took him through a long corridor of lined-up police who were kicking and punching detainees as they arrived at the sports hall. “I couldn’t see how many people had hit me in the face, in the head, and I was subjected to insults and inhumane treatment,” Özmen said.

He was brought to one of the desks that were set up at the entrance of the hall and manned by doctors. He was ordered to strip down to his underwear and was hit with handcuffs in front of the doctors who were supposed to report abuse and torture. He passed out from the beatings in front of the doctors; yet his medical reports said nothing, confirming that the doctors were pressured and threatened to not record anything in the documents. There are seven medical reports in his case file from the time he was in custody, but none of them reflect the torture he was subjected to.

Doctors filed medical reports that said nothing about torture and abuse for fear of retribution by the police:

“[Then] they threw me into the main hall, and the minute I stepped inside, I thought it was an apocalyptic scene. There were hundreds of people lying on the ground, covered in blood, some just collapsed and abandoned on the floor, some of being kicked and insulted by police in civilian clothes,” he said.

The police who took him to the main hall called out to several officers who were in the middle of the hall and chatting among themselves. “All those cops started running towards me, and as soon as they came up to me, they started hitting me. I braced myself, covered my face and fell to the ground, but that didn’t help. They started hitting me wherever they found an opening, and they were yelling and swearing,” Özmen told the court.

They were telling him that his wife and daughters were “halal” to them, meaning they could rape them at will and treat his family members as the spoils of a jihadist battle.

The police officers were hitting him with plastic cuffs, using them as whips. Özmen did not know how to protect himself from the blows. “If I turned right, they hit me on the right, if I turned left, they hit on the left. I decided to keep still, and when I didn’t move, they left me, thinking I had fainted,” he added.

But one officer was not satisfied with the beating. He pulled him off the ground and threw him hard back to floor again. Then he started kicking Özmen in the head. Blood was gushing out, covering his entire face. Then the police grabbed him and dumped him next to a pole in the court. He could barely see through the blood in his eyes but noticed that another officer was approaching him at that moment. That police officer took him back to the middle of the court and started beating him again. Other officers later joined in the beating.

When he opened his eyes, he was back at the pole, lying next to his comrade Abdulkadir Baytak, who was also brutally beaten. His could barely move due to broken ribs and had difficulty breathing.

Özmen was tortured, beaten and abused for days, with teams taking shifts. Some torturers were not from the police department according to him, corroborating the accounts of other victims in the hall who testified during hearings that staff from the intelligence agency MIT also participated in torture sessions.

They stayed for a few days in their underwear in the hall, which was covered in blood, urine, feces and broken glass. He had to remove a piece of glass stuck in his foot using another shard as a knife after his request for a doctor was rejected. They were denied sleep, food, water and bathroom visits as a form of torture, forced to stay in stress positions for hours and ordered to duckwalk around the hall.

“I was beaten repeatedly until my entire body turned black and blue and was covered in blood. During one of these forced marches, police handcuffed me from behind, kicked me in the face and worked on me for some time, forcing me to kneel down and and sexually harassing me,” Özmen told the panel of judges.

He witnessed people in the hall having seizures and screaming from the abuse and torture. Then the police intensified torture even further, beating them until they passed out. The police woke them up with water and kept hitting them until they fainted again, he said, stressing that the police were clearly hitting with an intent to kill.

Once a day the detainees were brought to doctors who were in the hall to process paperwork. Before the visit, they received a beating and warning that they would not complain. The doctors were told to not indicate any abuse or torture in the medical examination reports. “The doctors couldn’t document the beatings and torture they saw out of fear. The police said there was no torture and rushed us out of the room right away,” Özmen said.

He added that he witnessed the lifeless bodies of several gendarmes on the floor in one of the rooms that were used for medical dressings. “They were people I knew as gendarmerie personnel, but I didn’t know their names. I was shocked to see them, their faces were no longer visible, their bodies were bloated because of heavy swelling… I presumed they were dead, and the police told me to get out of the room,” he said.

At night, he was taken to special interrogation rooms and tortured there. The police also threatened him with harm to his family members unless he signed a prepared statement identifying people whom he didn’t know as accomplices. He said he didn’t remember how many times he was taken to these rooms but that on one occasion he was forced to stay in a stress position under a chair for hours. Those who had the night shift were the most brutal, he said.

The wounds on his head required stitches, but the doctors simply poured a disinfectant on them and sent him away. Because of the open wounds and lying on the floor in urine and blood, the detainees started to smell, which actually helped them avoid further torture, according to Özmen The police could not approach them because of the stench or had to wear masks. After eight days the entire hall smelled, and the police had to allow detainees to take showers in the locker room.

They were given an orange shirt, pants and slippers before they were taken to court for arraignment. On the way they were once again threatened to not speak about torture or face another round of torture after the hearing. The same police officers who tortured them in the hall accompanied them to court.

The judge at his arraignment was not interested in hearing his statement and lashed out at him:

Judge Yaşar Sezikli was angry at Özmen’s arraignment on July 24, 2016 following seven days of torture and lashed out at him when Özmen tried to explain what had happened at gendarmerie headquarters on the night of July 15. “The judge suddenly threw the case file in front of me in a rage and said, ‘Give me a name, stop telling stories.’ He stood up and said, ‘Give me names’,” Özmen said. “After everything I had been through, I couldn’t understand why the judge was acting this way, but after three years, I now understand why I was subjected to such treatment that day,” he said, adding that the authorities were not interested in finding out the truth of the July 15 events but were bent on justifying a mass purge in the military carried out based on dubious evidence and sham trials.

Document that shows it was Judge Yaşar Sezikli who held the arraignment hearing during which he lashed out at Özmen:

Although he filed criminal complaints against his torturers, Turkish authorities did not act on allegations, protecting those who had abused him and many others.

Torturers in Turkey were protected by a government decree issued by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that provided blanket immunity for officials who were involved in coup investigations. Decree-law No. 667, issued by the government on July 23, 2016, granted sweeping protection for law enforcement officers in order to prevent victims from pressing complaints of torture, ill treatment or abuse against officials. There were multiple cases in which Turkish prosecutors refused to investigate torture allegations, citing this decree-law, or KHK (Kanun Hükmünde Kararname).

Article 9 of this KHK stated that “legal, administrative, financial and criminal liabilities shall not arise in respect of the persons who have adopted decisions and fulfill their duties within the scope of this decree-law.” The decree was criticized by human rights organizations for being a clear violation of articles of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) as well as the European Convention on Human Rights, to which Turkey is a party, yet it was never annulled. In fact, the Turkish parliament passed the decree into law on October 18, 2016.

As of today, no prosecution has been initiated against people who tortured detainees at unofficial sites despite multiple complaints filed by the victims and their lawyers.

The abuse even continued during the trial, when Özmen and other defendants were kept in a room in the basement of the courthouse that was leaking toilet water from the ceiling. “Your Honor, before starting my defense statement, I want to talk about the toilet water dripping on us in the detention room. We have complained about this many times, but no action has been taken. After being kept waiting in an inhuman condition, I’m sorry to say this, Your Honor, but I was brought before you smelling like human feces,” he said at a November 2019 hearing.

Court testimony of Abdulhamit Özmen reveals that the defendants were kept in a waiting room that was leaking toilet water and given expired food before the hearing:

He also showed the judges food he was given in the detention room that had passed its expiration date. He asked that the record reflect that he and other defendants had been treated like this for the last three years during the trial and that the authorities did nothing to remedy these abuses. During the hearing, Özmen had to ask for a recess because of a sick feeling in his stomach that he claimed had to do with the food he had eaten.

Despite a lack of evidence, Özmen was convicted on coup charges and sentenced to aggravated life at the end of the trial in June 2020.

Full testimony of Abdulhamit Özmen at the Ankara 23rd High Criminal Court on November 10, 2019:

Initial testimony in the same court on April 17, 2018: