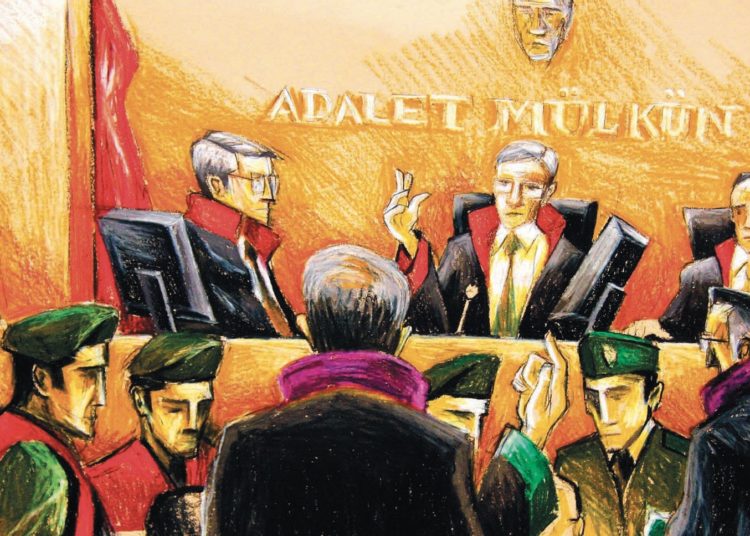

In a sign of how the Turkish judiciary has been rendered incompetent and abusive in the hands of the regime of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a Turkish judge in September 2018 requested that the United States extradite a government critic, incorrectly citing a European convention.

Judge Muhammet Zafer Terzi, a partisan judge who was selected to oversee politically motivated criminal prosecutions that targeted critics of Erdoğan, asked US authorities to hand over a doctor, citing the 1959 European Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters. The problem with the judgement is not only that the United States is not party to the agreement but also that the US and Turkey have a 1979 bilateral extradition agreement that would govern this type of request.

The ruling shows how the regime’s current judges are not competent to handle such sensitive legal requests since more than 4,000, or some 30 percent, of all judges and prosecutors were purged and/or imprisoned following a failed coup in 2016. It was clear that Judge Terzi was ignorant of the fact that the 1979 Turkish-US extradition agreement even exists. Instead of invoking any of the 33 criminal offenses listed as grounds for extradition between the two countries, the judge cited an agreement that is not relevant for a person who resides in the US.

The 1959 European convention entered into force in 1963 and has thus far been ratified by 50 states including three non-European nations. The US is not among the non-European states that acceded to the convention. The agreement was upgraded in 1978 with the Additional Protocol to the European Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters and later with the Second Additional Protocol to the European Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters in 2001. In the ruling the judge also cited the Second Additional Protocol as grounds for extradition but indicated the agreement date as 1987, which is not the case.

The person targeted by the judge was a Turkish national identified as Kudret Ünal, a 71-year-old man who is claimed to be the doctor of Fethullah Gülen, a vocal critic of President Erdoğan who has been living in the US since 1999. In the court papers, Ünal was accused of “terrorism” and “coup plotting,” which could land him in jail for life, but there is no evidence that supports any of these serious accusations. Among the evidence that was cited by Judge Terzi were critical tweets posted by Ünal,

The doctor was a shareholder of publishing and media company Nil from 2003 until 2015, when the government unlawfully seized the firm. He was also a shareholder in the Çağlayan publishing house between 1990 and 2013. Both firms were legal entities that were subject to Turkish laws and operating under business licenses authorized by the government. The firms, whose shareholders were linked to the Gülen movement, became targets after a major corruption investigation in 2013 that implicated Erdoğan and his family members as well as his business and political associates.

The judge claimed Ünal was also flagged as a criminal because he had deposits in Bank Asya, once the largest Islamic lender and one of the biggest private banks in Turkey until it was unlawfully seized by the government in May 2015. The bank, which had 210 branches, 5,000 employees and around 1.5 million clients, was founded on October 24, 1996 upon the formal approval of banking regulators. It operated under the supervision of the independent regulatory bodies in Turkey that were responsible for overseeing the banking sector. At least 700,000 people were reportedly put under investigation for their connections to the bank.

The bank was one of three with the highest liquidity in Turkey, yet it was targeted by Erdoğan because its shareholders included investors who were seen as close to the Gülen movement. Erdoğan first tried to trigger a run on the bank by wrongfully claiming that it was bankrupt but failed in that endeavor. He then orchestrated a legal case to take over the bank using partisan prosecutors. The government not only went after the shareholders and bank managers but the account holders as well.

Although the judge admitted that Ünal left Turkey via Istanbul Atatürk Airport on October 26, 2014 and never returned according to customs data, the defendant was accused of attempting to topple the government on July 15, 2016 when a failed coup took place. In other words, he was out of Turkey, yet he was accused of involvement in the attempt. No evidence was presented to support this claim.

Judge Terzi, who oversees the Istanbul 33rd High Criminal Court, said the court issued an arrest warrant for Ünal on April 19, 2018 and that the statute of limitations on his crime will run out in 2048, when the defendant turns 100. Terzi also claimed that the charges were not politically motivated in an attempt to allay US concerns. The US-Turkey extradition agreement rules out turning over people sought on politically motivated charges.

Turkey must complete a series of legal procedures and meet evidentiary standards before any official extradition request is granted by the United States. The agreement stipulates that extradition will not be granted for an offense if it is of “a political character,” or where extradition seeks to prosecute or punish a person “on account of his political opinions.” In the case of Gülen and Dr. Ünal, it is clear that Erdoğan and his judges were going after critics on politically motivated charges and wanted to punish them for their political views.

On July 19, 2016 Turkey submitted to the US a request to arrest Gülen, and on July 23, 2016, formally submitted an extradition request. After reviewing the requests, the US Department of Justice informed its Turkish counterpart that the requests had not yet met the legal standards for extradition required by the US-Turkey extradition agreement and US law. Accordingly, the Department of Justice noted, extradition could not go forward, absent additional evidence substantiating the allegations.