A front Turkish charity that was named by Russia as a sender of arms and supplies to jihadist groups in Syria with the help of the government received donations from the Turkish assassin of Russian Ambassador Andrei Karlov, documents reveal.

According to investigation reports prepared by the Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK), hitman Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş, the 22-year-old riot police officer who gunned down the Russian diplomat in December 2016, transferred money to the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (İnsan Hak ve Hürriyetleri ve İnsani Yardım Vakfı, or IHH). The reports show that the killer sent TL 1,584.13 to IHH accounts in 11 separate transactions between January 2015 and July 2016.

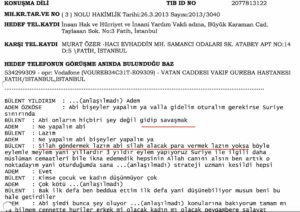

The MASAK reports of Feb. 16, 2017 and Dec. 23, 2016 examined accounts owned by the killer with Islamic lenders Kuveyt Türk and Albaraka Türk. The reports were later incorporated in an indictment concerning the murder of Karlov filed with the court by Turkish prosecutor Adem Akıncı.

Another reference to the IHH in the Karlov indictment was made by witness Mikail Bora, who had been attending religious sermons in Ankara along with the killer, Altıntaş. Bora told the counterterrorism police in a statement he gave on Jan. 6, 2017 that he worked for the IHH. Bora also admitted that he saw the killer at these sermons given by radical cleric Nurettin (Nureddin) Yıldız in Ankara. Yıldız’s own NGO, the Social Fabric Foundation (Sosyal Doku Vakfı), set up a volunteer group in Ankara under the name of Sosyal Doku Ankara Gönüllüleri Grubu (Social Fabric Ankara Volunteers Group), and Altıntaş was in contact with this group starting in 2014, attending study circles.

This extremist preacher is often described as the family cleric of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and was paraded as a keynote speaker at youth events organized by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and conferences and lectures organized by the Turkey Youth Foundation (TUGVA), which is run by Erdoğan’s family. He even travelled to Syria to meet with militant groups and often preached in support of violent jihadist campaigns around the world.

Yet in a bizarre twist, the prosecutor did not question these wire transfers nor did he summon anybody from the IHH to inquire about the transactions or the purpose of the funds. Furthermore, the indictment reveals that the prosecutor did not list any administrator from the IHH either as a suspect or as a witness, meaning he did not pursue the IHH avenue further, although both the wire transfers and witness testimony pointed to the IHH.

This was not the first time the IHH had escaped the scrutiny of criminal investigations in Turkey. The network of this highly controversial charity group was accused of smuggling arms to al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadists in Syria in January 2014 in an investigation conducted by a prosecutor in Turkey’s eastern province of Van. The investigation into a Turkish al-Qaeda cell found that İbrahim Şen, a top al-Qaeda operative who was detained in Pakistan and jailed at Guantanamo until 2005 before he was turned over to Turkey, his brother Abdurrahman Şen and others were sending arms, supplies and funds to al-Qaeda groups in Syria with the help of the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MİT), which is run by Erdoğan’s close confidant Hakan Fidan, another Islamist.

The investigation led to the IHH when wiretaps and surveillance revealed that the Kayseri and Kilis branches of the IHH were sending funds and medical and household supplies to jihadists in Syria. Investigators discovered that Şen enlisted the help of the IHH when he wanted to conceal illegal shipments to jihadists. The prosecutor’s conclusion was that this NGO took part in this scheme knowing full well what it was involved in. It was not random or individual participation but rather a deliberate scheme with the knowledge of IHH management.

Three people identified by the police as partners with Şen in smuggling goods to Syria were Ömer Faruk Aksebzeci (working out of the IHH Kayseri branch), Recep Çamdalı (member of the IHH’s Kayseri branch) and İbrahim Halil İlgi (working out of the IHH Kilis branch). Fearing that the expansion of the probe could lead to senior figures in the IHH and expose the links to his government, Erdoğan quickly moved to quash it. The government dismissed and later arrested all police chiefs and prosecutors who uncovered the IHH’s clandestine dealings with jihadist groups.

The irony in the case of the murder of the Russian ambassador is that the IHH had long been flagged by Russia as an organization that smuggled arms to jihadist groups in Syria, according to intelligence documents submitted to the UN Security Council on Feb. 10, 2016. In other words, while the envoy’s killer was transferring funds to the IHH, Russian Ambassador Vitaly Churkin, permanent representative to the UN, was lobbying against the IHH and submitting documents that showed how dangerous the group was. Russian intelligence documents even furnished the license plate numbers of trucks dispatched by the IHH loaded with arms and supplies bound for al-Qaeda-affiliated groups including the Nusra Front.

What is more, the leaked emails of Berat Albayrak, the son-in-law of Turkey’s Islamist President Erdoğan and current finance and treasury minister, have provided clues as to how the IHH was cited as a strong reference in the resume of applicants when it came to grooming candidates for positions in the government. In an email dated Nov. 10, 2015 İsmail Emanet, a close friend of Erdoğan’s son Bilal, sent the CVs of five candidates to Albayrak for review with a note saying that they had been selected to become Russia experts as part of a program run by the Erdoğan-family-managed-NGO TÜGVA. Emanet is president of TÜGVA, while Bilal and his friends serve on the advisory board.

One candidate recommended by Emanet was 21-year-old Mücahit Türk, who he said came from an IHH background. Mücahit’s mother Fatma Türk, also listed as a reference in the note, is the chairwoman of the IHH’s women’s branches and actively campaigns across Turkey for President Erdoğan and the IHH. In his own note attached to the recommendation, Emanet told Albayrak that the student was very much interested in Russia, had developed a strong sense of religious obligation due to his upbringing and was deserving of being selected.

Another document from the authenticated email communications of Erdoğan’s son-in-law also implicated the IHH in arming Libyan factions. The secret document tells the tale of how the owner of a bankrupt shipping and container company asked for compensation from the Turkish government for damage his ship sustained while transporting arms between Libyan ports at the order of Turkish authorities in 2011. The document revealed all the details of a Turkish government-approved arms shipment to rebels in a ship contracted by the IHH.

The secret documents obtained by Nordic Monitor clearly show that the head of the IHH, Bülent Yıldırım, has been in bed with the Turkish spy agency in running jihadist networks from Syria to Turkey. They also reveal the extent of his network with the Turkish government at the Cabinet level. It lays bare how the grass roots of the IHH were mobilized by the government of Erdoğan when the Turkish president needed political cover in the face of public pressure and criticism.

The secret investigation included the transcripts of 142 wiretaps that were duly authorized by the courts between Jan. 6, 2013 and Dec. 17, 2013 as part of an investigation into radical Islamist groups. They identify a man named Veli Çayır, an intelligence officer who worked as the right-hand man of Fidan, the head of the Turkish spy agency. It seems like the IHH head had a special hotline to Çayır and called him whenever he felt he needed to share information on developments in Turkey and abroad where the IHH had operations under the cover of charitable work. In wiretapped evidence dated Feb. 25, 2013, Çayır made clear to Yıldırım that he was assigned to work with him under specific orders from MIT Undersecretary Fidan and could call him day or night if needed.

The records show they tried to avoid divulging secret information on the phone and preferred to use couriers to send sensitive messages or meet in person in secure locations. At times Yıldırım appears to have visited MIT headquarters in Ankara’s Yenimahalle district. Nevertheless, they inadvertently released much information on the phone as they spoke. The information gleaned from the wiretaps is enough to tie the IHH to Turkey’s notorious intelligence agency. Given the fact that the IHH has penetrated many countries abroad including in Europe under the guise of charitable and humanitarian work, there are enough reasons to be concerned about Erdoğan’s long arm stretching to Turkish and Muslim diaspora communities.

On May 4, 2013 Yıldırım talked to Adem Özköse, a journalist known to be close to jihadist groups, and said they should go and fight in Syria. When Özköse asked what exactly they should be doing in Syria, Yıldırım said arms should be sent to Syria or funds must be provided so that jihadists can purchase arms. He said he got fed up with protest meetings as they were futile for getting results. In a wiretap on Nov. 23, 2013, the IHH president brags about how he chided Muslim scholars who criticized the IHH for carrying arms under the guise of humanitarian aid. He said he told them the IHH can only send small arms in aid packages, while others are sending missiles.

The new confidential documents expose how IHH President Yıldırım was intimately involved with rebels in Syria. For example, on May 28, 2013 Yıldırım called his contact at MIT, informing him that the IHH was hosting Zahran Alloush, the head of Liwa al-Islam (which later changed its name to Jaysh al-Islam), a Salafist jihadist group active around Damascus, in Turkey and wanted to arrange a meeting between him, his deputy Abu Nour and MIT officials. Alloush was later killed by a Syrian Air Force airstrike, on Dec. 25, 2015.

In another call on June 12, 2013, Fidan’s aide Çayır phoned the IHH chairman, asking him to provide support for the Al-Rahman Legion (Faylaq Al-Rahman), an armed opposition group that had a base near the Turkish-Syrian border crossing at Cilvegözü (Bab al-Hawa). He said the group was running low on supplies and asked the IHH to replenish his stocks. On Aug. 16, 2013 Yıldırım let his handler at MIT know that a man was caught in Syria and had important information. His man recorded everything in the video and wanted to send the footage to the intelligence service in Ankara. In a phone conversation that took place on May 13, 2013, Yıldırım told Çayır about a militant who would come to Turkey to stage an attack on members of the Turkey-backed Syrian National Council (al-Majlis al-Watani), which is based in Istanbul. He said he picked up the intel from a reliable source.

In a phone call on July 11, 2013, Yıldırım talks about an operation that involves a border crossing by a group in Syria and tells Çayır he has misgivings about the people selected for the operation and underlines that they may fail in their task. He says he would coordinate the action with intelligence officers on the ground. He also shares that IHH teams identified villagers who possess a highly dangerous chemical substance that is used in refining oil.

In a wiretap dated March 23, 2013 IHH head Yıldırım and MIT official Çayır talk about how to finalize a prisoner swap in Syria where a female officer from the Syrian army was caught by rebels and handed over to the IHH in exchange for the release by the Bashar al-Assad government of a captive opposition fighter. According to the plan, the woman was supposed to be picked up in Aleppo by the IHH and handed over to MIT for transfer to Iran.

The IHH continues to operate freely today with the support of the Erdogan government and even acquired United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) membership with the help of Turkey and its Islamist allies.