An ailing 71-year-old Turkish businessman who was thrown in jail on trumped-up terrorism charges has suffered ill treatment and abuse in detention and prison facilities in Turkey. The long pre-trial detention and unlawful prosecution have destroyed his life, while authorities froze his bank accounts, depriving him of the necessary funds to support his ill wife and 98-year-old mother, both in need of constant care.

The abuse, documented by his statements in court and medical reports obtained by Nordic Monitor, reveals the systematic and deliberate campaign of torture and ill treatment of victims in Turkish prisons and detention facilities. As if the ordeal he went through were not enough, he was mocked by a judge at his first hearing when he had a chance to relate his story. His case is one of many in an unprecedented crackdown pursued against critics, opponents and dissidents by the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Mehmet Emin Bayram appeared for the first time before the Istanbul 33rd High Criminal Court on June 25, 2018 to give a defense statement after he had spent a year in pre-trial detention following a police raid on his home in the early hours of June 6, 2017. He was dragged to a detention facility at the main police headquarters on Istanbul’s Vatan Street. He spent three days in detention before he was formally arrested during his arraignment by the Istanbul 5th Criminal Court of Peace on dubious terrorism charges. Authorities charged this old man with membership in the Gülen movement, a civic group led by US-based Turkish Muslim scholar Fethullah Gülen, a vocal critic of President Erdoğan.

Bayram was first transferred to Metris Prison in Bayrampaşa and then moved to the notorious Silivri Prison five days after his arrest. He had no criminal record and had never visited a police station in his life. A graduate of the state art academy, he worked as an architect for the government for 10 years before moving to the private sector in 1984. He ran various business enterprises in Istanbul, from construction to retail. He told the court his 390-day pre-trial detention had turned into a punishment in itself although he had not been convicted of any crime.

Describing the abysmal conditions in the detention facility where he shared a small cell with two other people, Bayram said he had slept on a mattress on the floor, was deprived of adequate food and water and was allowed very little time to use the bathroom facilities. He suffered from heart problems as well as difficulty in breathing, and the police had to call emergency services after his cellmates alerted them to his condition. He was rushed to the emergency room at Istanbul Haseki Teaching and Research Hospital. After treatment, he was sent back to the detention facility.

As Bayram was about to further explain what had happened on his second day in detention during the hearing, he was cut off by presiding judge Muhammed Zafer Terzi, who said he should instead respond to the allegations raised in the indictment. Bayram replied that he would tackle the charges soon enough but wanted to put what he had experienced in the record, saying this was his first opportunity to speak out after 13 months in pre-trial detention. In a flagrant breach of trial procedure, Terzi continued his interruptions, saying he had sent him to the Council of Forensic Medicine (Adli Tıp Kurumu, or ATK) for examination. Bayram said he would talk about that as well. Yet the judge made a further warning that if Bayram prolonged his statement, it would shorten the time for other defendants in the trial. The judge’s intervention was out of line, and he also mocked him, made political statements and displayed his bias against the defendant, the transcripts of the hearing reveal.

Bayram went on sharing his experiences on his second day in custody, during which he was taken to a doctor of internal medicine on a referral from the emergency room examination a day earlier. The doctor ordered an X-ray, from which he determined that Bayram’s lungs displayed serious problems. He also made an urgent referral for the patient to see a pulmonologist. “The police did not take me to the specialist, however,” Bayram complained, adding, “They [the police officers] told me they would take my statement right away and then send me on my way.”

On his third day in custody, he was supposed to give the statement and be released as promised. However, on orders from the prosecutor, Bayram was taken to court, where the judge ruled for his arrest. His health problems continued and in fact worsened in prison. He was rushed to the emergency ward nine times, had trouble breathing in his overcrowded cell and developed an ailment in his liver in addition to the already poor condition of his lungs. Problems with his urinary tract, high blood pressure and back and leg pains deteriorated further.

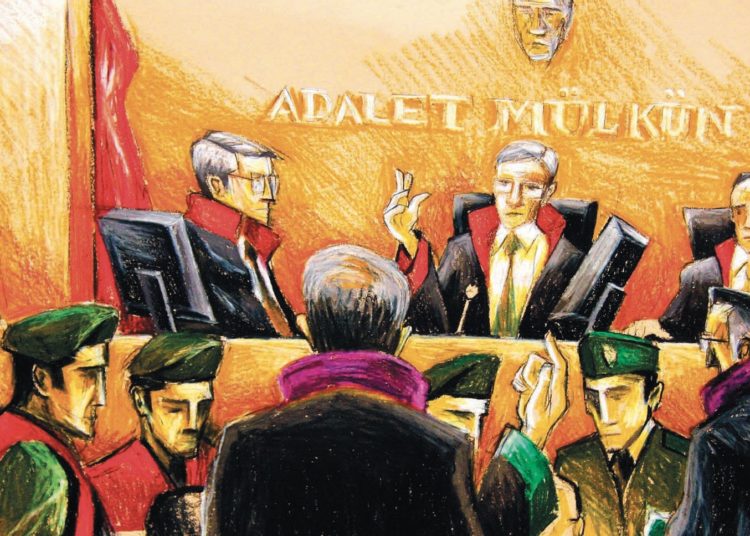

Mehmet Emin Bayram’s court testimony.

According to a motion filed by his lawyer, Nesrin Öztürk, his lungs were operating at 40 percent capacity but were stable and under monitoring by his doctors. She submitted half a dozen hospital records verifying his pre-detention health. Bayram’s lungs worsened in prison because he was put into a jail of 40 people with capacity for only 10. She said her client’s health had deteriorated so badly that he was at risk of a heart attack, brain hemorrhage and paralysis. The prison administration also refused to take him to the nearby Silivri State Hospital despite the fact that several appointments had been booked for a medical examination and treatment.

The prison referred him to a state-run ATK hospital where he was hurriedly examined by a doctor who scandalously decided that he was fit for prison without even bothering to run any medical tests. His lawyer challenged the decision and asked for a comprehensive review by medical experts at a state hospital, but the prison officials refused to take him there. Both lawyer Öztürk and her client repeatedly petitioned to obtain his medical records from the prison infirmary where Bayram was treated many times in emergency situations, but the officials refused to turn them over.

The old man responded to the serious accusations of terrorism leveled against him in the indictment by the prosecutor. One piece of evidence presented against him was a deposit made in 2014 to his account At Bank Asya, once Turkey’s largest participation bank that had been owned by shareholders close to the Gülen movement. The prosecutor alleged that the deposit was made on the orders of Fethullah Gülen after Erdoğan attempted to spark a run on the bank with public and unfounded accusations. Bayram denied the charges and said he had been using Bank Asya’s services since 1998 because of their competitive rates and favorable terms for his business transactions. He said he received his government pension in this bank account and paid invoices on the same bank. Bayram also refuted allegations that he increased his balance at the bank in 2014 and presented statements proving that he actually withdrew all his money from Bank Asya in March 2014 to give as a loan to his son.

Bayram, a long-time businessman and well-known figure in Istanbul’s Üsküdar district, told the court he could not even pay his property and municipal taxes for the first time in his life because the authorities had frozen his bank accounts, put a lien on his properties so that he could not liquidate his assets or collect income from leased properties. “I have a sick wife who needs constant care and a 98-year-old mother who also needs care and who does not even know that I’m in prison,” he explained. He said the court needed to remove the lien on his assets and properties so that he could collect income to support his family and settle his debts. Underlining that his business had never suffered before, never had legal problems with any of his business partners and never had an unpaid debt, Bayram said his reputation and business interests had been destroyed after his unlawful arrest in 2017.

He was tried in a case involving Kaynak Holding, a major conglomerate and the largest publisher in Turkey, which was unlawfully seized by the Erdoğan government on fabricated charges of terrorism in November 2015. Kaynak, a group that operated 22 major companies under its umbrella, was owned and operated by businesspeople seen as affiliated with the Gülen movement. The prosecutor accused him in the case file of doing business with Kaynak and its affiliated companies. Yet the defense presented documents showing that he had no relationship with any of the Kaynak firms but had made a donation to an organization affiliated with the Gülen movement when the government had no problems with the group.

Bayram’s abuse and ill treatment in prison and detention, documented in his testimony and the defense statement in court docket No. 2018/82, is only the tip of the iceberg of the widespread torture that was carried out at different levels and to varying degrees in Turkey. This alarming situation and relevant cases have been covered by the UN and nongovernmental organizations in recent years.